A woman has been found not guilty of murder by reason of mental illness after driving her Ford Falcon station wagon at speeds up to 200km/h into the back of a Harley-Davidson rider, killing him.

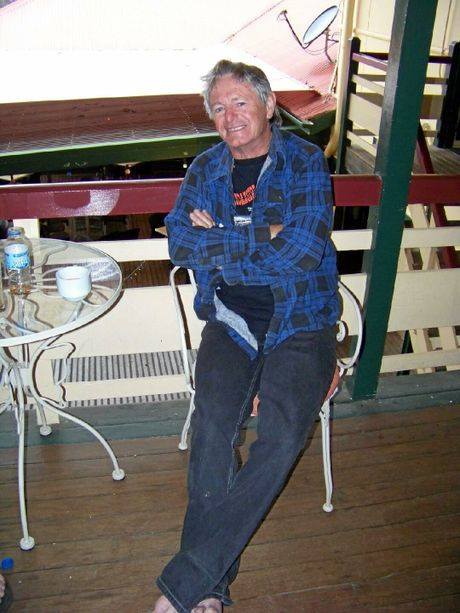

Tweed Heads father of three Trevor Moran, 61, was treated by NSW Ambulance paramedics but died at the crash scene on the Pacific Highway near the Cudgera Creek, on 6 January 2017.

Vanessa Fraser, then 47, was found not guilty of his murder by the Sydney Supreme Court on Tuesday 23 October 2018.

Her defence included claims that her car was “possessed” and that she was off her medication at the time of the incident.

The Crown had the accused examined by its own psychiatrist, Dr Anthony Samuelsa, who evaluated Fraser as suffering “psychotic illness with paranoid delusions”.

Court heard that Fraser told paramedics and police immediately after the accident that she heard “a male voice in my head saying I wanted to kill Ewan McGregor”.

On October 25, Supreme Court Justice Des Fagan published his reasons for the judgment. Click here for the full text or go to the end of the article.

He basically says that there is reasonable doubt Trevor’s death was caused by a voluntary act by Fraser due to mental illness.

The official Supreme Court order says Fraser will be remanded in custody or “in such other place as the Mental Health Review Tribunal may hereafter direct until she is released by due process of law”.

Vale Trevor

Trevor was a much-loved member of the Tweed Heads Motor Cycle Enthusiasts Club.

The court heard Trevor’s death had a “devastating effect” on his family and friends.

When Fraser first appeared in Lismore Local Court, her case was adjourned and she was sent to the mental health unit of the Sydney jail.

She was remanded in custody since and there were three court subsequent adjourned appearances.

Supreme Court Justice Des Fagan’s judgement:

- On 22 October 2018 Vanessa Fraser was arraigned before me on a charge that on 6 January 2017 at Cudgera Creek in the State of New South Wales she did murder Trevor William Moran. Death was alleged to have been caused by the accused driving a station wagon at high speed into the rear of Mr Moran’s motorcycle as he was riding it north on the Pacific Motorway about 35 kilometres north of Byron Bay.

- The accused pleaded not guilty. The trial proceeded before me without a jury. The Crown consented on 30 January 2018 to the accused’s application under s 132(1) of the Criminal Procedure Act 1986 (NSW) for a judge-alone trial. Fullerton J so ordered on 9 February 2018, as her Honour was required to do by s 132(2).

- The charge was defended only on the basis of the mental illness defence under s 38 of the Mental Health (Forensic Provisions) Act 1990 (NSW). In response to a report of Dr Furst of 19 September 2017 prepared on behalf of the accused, the Crown had the accused examined by its own psychiatrist, Dr Anthony Samuels. Dr Samuels provided a report of 24 November 2017 in which he agreed with Dr Furst that at the time of the collision the accused suffered from a disease of the mind, namely a psychotic illness with paranoid delusions, from which she was under such a defect of reason as not to know the nature and quality of her own acts or that what she was doing was wrong.

- The Crown provided Dr Samuels’ report to the accused and tendered it in its own case, in proper discharge of the Crown’s duty of fair presentation to the Court of all relevant evidence. Having regard to Dr Samuels’ conclusions the Crown has not contested the availability of the mental illness defence and has left it to the Court to satisfy itself that a special verdict of not guilty by reason of mental illness is appropriate.

- The elements of the offence of murder as charged on the case run by the Crown are as follows:

- That Trevor Moran died on 6 January 2017 at Cudgera Creek.

- That voluntary actions of the accused caused his death.

- That those voluntary actions were done with intent to cause his death or with intent to cause him grievous bodily harm, meaning really serious physical harm.

- To arrive at a verdict of guilty I would have to be satisfied that the Crown had proved each of these elements beyond reasonable doubt. Element 1 may be dealt with very shortly. The evidence of Senior Constable Dunne establishes that Mr Moran died at the scene of the collision. An autopsy was carried out by Professor Timothy Lyon on 11 January 2017. Professor Lyon’s report satisfies me that Mr Moran sustained in the collision multiple injuries to his head, spine, chest and abdomen which were not survivable. These principal injuries, together with others to his limbs and extremities, were “consistent with being struck at high speed from behind while travelling on a motorcycle and subsequently being ejected from the cycle and impacting with the ground.” The accused has not contested that Mr Moran was killed in the collision and that element is found beyond reasonable doubt.

- With respect to element 2, the causation of death by voluntary act of the accused, I must first make findings of primary fact concerning the collision. I will then consider what may be inferred from those primary facts with respect to the accused’s actions. There is no direct evidence from any eyewitness to the collision. The Crown’s case that the collision and therefore Mr Moran’s death were caused by voluntary acts of the accused depends upon circumstantial evidence. I therefore could only find element 2 proved beyond reasonable doubt if I should be satisfied that no reasonable hypothesis consistent with innocence can explain or fit in with the body of circumstantial evidence.

- If I conclude on element 2 that the collision and the death of Mr Moran were the result of voluntary actions of the accused then before proceeding to consider whether the Crown has proved the specific intent to kill or to cause grievous bodily harm (being element 3, an essential ingredient of murder) it would be necessary for me to determine whether the accused is criminally responsible for her voluntary actions which were causative of Mr Moran’s death. The mental illness defence is to be determined at that point, before examining the Crown’s proof of specific intent: see Hawkins v The Queen(1994) 179 CLR 500; [1994] HCA 28 and R v Minani (2005) 63 NSWLR 490; [2005] NSWCCA 226.

- The accused’s manner of driving was observed by ten witnesses who saw her vehicle northbound on the Pacific Motorway at various points over a distance of slightly more than 30 kilometres leading up to the collision site. The collision occurred at about 8.30 am on Friday 6 January 2017. The witnesses made their observations over the preceding 10 minutes. Their time estimates were for the most part admittedly and understandably rough but some of the witnesses were able to fix times by reference to records of phone calls made or received.

- Nine of the witnesses were driving north, in the same direction as the accused, and were proceeding at about the speed limit of 110 kilometres per hour. The earliest observation was by Mr Jared Hall at a point 31.6 kilometres south of the collision. The accused overtook him on the inside at a speed and in proximity sufficient to make his own vehicle shake. Mr Hall estimated her speed at 200 kilometres per hour, relying upon his experience in car racing and motor sports over many years. He saw the accused’s white Ford Falcon station wagon swerve from lane to lane overtaking other cars as it disappeared out of his sight. He came upon the collision scene about 10 minutes later. The accused had covered over 30 kilometres in that time, including an average speed of around 180 kilometres per hour.

- A second witness saw the accused’s vehicle being driven at high speed and weaving in and out of lanes to overtake other vehicles at a point seven kilometres further north of Mr Hall’s observations. This witness saw that on one heavy swerve between lanes the accused over-corrected and her vehicle was on two wheels before she regained control.

- These two witnesses and most of the other seven who were travelling in the same direction as the accused were taken by surprise by the speed at which her vehicle approached them from behind and overtook. Most of them observed her weaving dangerously from lane to lane and overtaking their own and other vehicles at high speed.

- Those who were able to estimate the accused’s speed nominated a figure or figures in the range of 160 to 200 kilometres per hour, which accords with the 30 kilometres covered by her in 10 minutes from the point of Mr Hall’s first observation to the collision site.

- A tenth witness to the accused’s manner of driving was a police officer travelling south. Because of his direction of travel and the relative combined speed of approach this witness saw the accused’s vehicle over a lesser duration than the others, namely about eight seconds. He estimated her speed at 160 kilometres per hour over a 400 metre straight.

- It is possible to infer the location and physics of the collision from marks on the roadway, from the resting positions of the accused’s vehicle and of Mr Moran’s motorcycle after the collision, from the nature of the damage to the vehicle and to the motorcycle, and from the position of Mr Moran’s body after the collision and the nature and extent of his injuries.

- The collision occurred in daylight in fine, clear weather. The point of contact was about 12 metres north of the Cudgera Creek Road overpass. This overpass runs east-west, crossing the Pacific Motorway at right angles. To the south of the overpass there is an off-ramp from the northbound lanes of the motorway leading off to the left and up to Cudgera Creek Road.

- There is an on-ramp extending north from the western end of the overpass down to the level of the motorway, providing a connection from Cudgera Creek Road to the northbound lanes of the motorway. This on-ramp joins the motorway at a shallow angle with a grass nature strip between the left-hand edge of the motorway and the right-hand edge of the ramp. The nature strip tapers away to the point where the ramp and the motorway merge.

- The point of collision was indicated by a rubber tyre scrub mark located to the left of centre of the left of the two lanes of the motorway. I accept the evidence of Crime Scene Officer Lennon that this mark was caused by the accused’s vehicle running on the rear wheel of Mr Moran’s motorcycle, buckling the rim inwards so as to lock the wheel against rotation and pushing it forward heavily across the road surface.

- Senior Constable Dunne compared damage to the front of the accused’s vehicle, in line with the driver’s position seat with the inward buckled rim of Mr Moran’s motorcycle. In a police holding yard Senior Constable Dunne placed the rear of the damaged motorcycle against the front of the station wagon and photographed the juxtaposition of damaged components. I accept his evidence and that of Officer Lennon that these photographs demonstrate how the vehicle and the motorcycle were oriented when they made contact.

- When this information is taken together with the position of the tyre scrub mark on the road and the linear direction of that scrub mark towards the left, it is an inescapable inference that the station wagon must have turned from the right towards the rear of the motorcycle immediately before contact and must have been straddling the continuous white fog line at the left margin of the motorway when the impact occurred.

- Other marks on the road indicate that Mr Moran came into contact with the surface about 20 metres north from the point of collision after separating from his motorcycle and that he then slid and/or tumbled a further 82 metres before coming to rest at the left hand edge of the paved surface of the motorway outside the fog line and adjacent to the grass nature strip. His motorcycle slid along the road surface for about 93 metres from the collision point and then across the grass strip for another 60 metres. It came to rest in the middle of the on-ramp, towards the bottom of it.

- The Ford Falcon station wagon which had been driven by the accused was deflected to its left by the collision and careered across the nature strip and across the on‑ramp to collide with a steel Armco barrier along the left hand edge of the on‑ramp. Witnesses who were on the on‑ramp very shortly after the collision observed that the station wagon rolled onto its side and slid in that attitude for some of this distance.

- The only significant injury sustained by the accused in the accident was a fracture of one vertebra at the junction of her thoracic and lumbar spine. After her vehicle righted itself upon colliding with the Armco barrier of the on‑ramp, the accused was able to get out of her car. At the scene she made numerous statements to other motorists who came to her aid and to ambulance officers who attended her and to police who restrained her.

- She also spoke with a paramedic in an ambulance on the way to Tweed Heads Hospital and to medical staff and to police after her arrival at the hospital. The things she said and her behaviour generally are consistent with her having then been in a psychotic state. However some of her statements are in my view reliable evidence bearing upon how the collision occurred. It is not inconsistent with her having been in the psychotic state identified by Drs Furst and Samuels, to which I will refer shortly, that she should have been able to give an accurate description of physical events of the collision.

- I place some weight on the following excerpts from the transcript of the recording of statements by the accused immediately after the collision, both at the scene and subsequently at the hospital. In the recording which commenced at 9.01 am her statements included the following.

[At p 8] I remember the car didn’t have any control and the car was going so fast — and then … swerved and hit the motorbike but I had no control, it was driving itself … .

[At p 9] I’ve been psychically attacked lately I’ve put that on Facebook 2 days ago, a photo of where I was being possessed.

[At p 11] I didn’t mean to hurt them, I promise I didn’t … . You’re treating me like I meant to but I didn’t, I promise.

[At p 11] Q. So do you have mental health history?

A. Yes, and I’m – – – I was badly abused as a child and I have post traumatic stress. … psychiatric history, been possessed over the last couple of days.

[At p 15] Q. Do you think, do you think you fell asleep?

A. No, it was like something took control of the car, it just went – – –

Q. Like it was possessed like you were possessed?

A. Yes, it was, it was, it was.

[At pp 21-22] A. Do you know what happened to the motorbike rider? … It wasn’t the actor Ewan McGregor somebody was like a male voice in my head saying I wanted to kill Ewan McGregor the next thing I know the car was swerving towards a motorbike.

Q. OK. So you heard a voice that said that – – –

A. A male voice, yes.

Q. Wanted to kill somebody and you swerved towards the motorbike?

A. No, no, no, no, I didn’t have control of the car, please, please believe me on that, I didn’t have control of the car.

Q. I’m just repeating what you say to me, OK? … I’m not putting words in your mouth, I’m just repeating what you say.

A. No, but can you read it out aloud because you said it different to how I said it and it makes a difference.

Q. I haven’t written anything down so I can’t read anything out.

…

A. The car was out of control, got out of control. … And did a turnaround, forward fast or, no, I don’t know what happened where it got turned around whether it was fast or not, it must’ve – – – if it was going the other way. Um, but then it was like a male voice, it wanted to get – – – He wanted to get Ewan McGregor. … And then that, that was him that it saw him and suddenly the car just swerved to the, to hit him.

[At p 22] Q. Are you saying that the car swerved to hit the motorbike rider?

A. Yes, yes.

[At p 28] I’ve been and I’m sure I’ve had people possessing me for years and I put a photo on Facebook a couple of days ago when I was being possessed and it fully looks like I’m possessed and it’s the creepiest photo you’ve ever seen in your life, and it happened last night or this morning.

[At pp 31-32] That it was Ewan McGregor and he wanted to get Ewan McGregor … But he didn’t tell me to hit him. … The car was out of control, it was out of my control. So please explain the difference. It was like he told me – – – and I did it, the car was out – – – of control.

[At p 35] A. The male voice was saying he wanted to get Ewan McGregor, was the motorbike rider Ewan McGregor, do you know?

Q. Ewan McGregor is a Scottish actor who lives overseas.

A. Yeah, okay, I’m just trying to work out what’s real and what’s not real. Oh my god.

- A further recording commenced at 1.54 pm. During the course of that the following statements were made and answers given by the accused:

[At pp 3-4] I … really have no idea what’s happened. I don’t know if you can answer this question. … But one … thing that I thought that happened was I was on the road and the car swerved to the left in the lane in the middle, it was on the, my car was in the right lane and it swerved to the left – – – to hit the motorcycle rider. … And then I recall going through grass and – and roll, it felt like the car rolling. But then when I came to, the car was on the side of the road and the motorbike behind, I, I, I don’t know what happened. Did the car get pulled or … what happened? I’ve got, I have honestly got no idea what happened, I really don’t. … Okay, does anybody know?

Q. Are you telling me that’s what occurred?

A. No. It’s partially only how it happened because my memory is of being in the right-hand le – hand lane and the car just swerving to the middle … and hitting the motorbike rider. No, swerving about a couple of metres behind him and then going into him … like 2 metres behind him. But then I really thought the sensation of then going, like, off an embankment and rolling through, definitely through grass and even the car rolling.

[At p 6] I can recall being on the right-hand side of the lane and the car swerving into the middle, it was going at breakneck speed, I think faster than a car should be able to go. It was crazy. And then it just went, like, a metre or, but, or two before the motorbike and then into it. And then I felt the sensation of rolling through … grass. I was even took my seatbelt to try and do stuff with the brakes ‘cause it was out of control. I was even bent down and the car was seriously, it was even driving itself for a bit. … and I, I rolled it, I’m sure I rolled, I definitely rolled through grass. I’m sure the car turned.

- On the totality of this evidence, including the accused’s post-accident statements, the physical indicators on the road surface and the descriptions given by witnesses, I am satisfied beyond reasonable doubt that by voluntary action the accused drove her car so as to approach Mr Moran’s motorcycle from behind at a speed in the order of 180 kilometres per hour, when he was travelling at a significantly lower speed. I am satisfied beyond reasonable doubt she swerved from right to left towards him from behind and collided heavily with his machine, with the results earlier described.

- Her consistent high speed for 30 kilometres over the preceding ten minutes continued unabated to the point of impact. Her statements during the aftermath, quoted above, support this. She expressed herself at that time as being distressed and she spoke in remorseful terms. Despite the delusional belief that she and her car had been taken over by something, or someone, which controlled and possessed them, she was able to describe the movements of the car and in doing so did not suggest that she had made any reduction in speed, or that in altering the course of her vehicle she was taking evasive action or anything similar. Her statements are readily reconciled with the physical evidence, except to the extent that she expressed the delusional belief something or someone had taken over physical control of her own actions.

- Being satisfied beyond reasonable doubt of this second element of the crime of murder, I must consider whether the accused has established that in law she is not criminally responsible for her actions by reason of mental illness. Section 38(1) of the Mental Health (Forensic Provisions) Act is in these terms:

If, in an indictment or information, an act or omission is charged against a person as an offence and it is given in evidence on the trial of the person for the offence that the person was mentally ill, so as not to be responsible, according to law, for his or her action at the time when the act was done or omission made, then, if it appears to the jury before which the person is tried that the person did the act or made the omission charged, but was mentally ill at the time when the person did or made the same, the jury must return a special verdict that the accused person is not guilty by reason of mental illness.

- Where the trial is by judge alone, of course, the trial judge must stand in the shoes of a jury to implement the requirements of that section. The Act does not contain any definition of what will suffice for an accused to be “mentally ill so as not to be responsible, according to law, for his or her action at the time when the act was done or omission made”. However the accepted meaning of this is as stated by Tindal LCJ in R v M’Naghten (1843) 8 ER 718 at 722:

[T]o establish a defence on the ground of insanity, it must be clearly proved that, at the time of the committing of the act, the party accused was labouring under such a defect of reason, from disease of the mind, as not to know the quality and nature of the act he was doing; or, if he did know it, that he did not know he was doing what was wrong.

- The accused should be found not to have known “the quality and the nature” of her acts in driving into the rear of Mr Moran’s motorcycle if she did not know the physical nature of what she was doing or the implications of it; see R v Porter (1933) 55 CLR 182; [1933] HCA 1. In that case Dixon J (as his Honour then was) said (at 189-190):

The question is whether he was able to appreciate the wrongness of the particular act he was doing at the particular time. Could this man be said to know in this sense whether his act was wrong if through a disease or defect or disorder of the mind, he could not think rationally of the reasons which to ordinary people make that act right or wrong? If through this disordered condition of the mind he could not reason about the matter with a moderate degree of sense and composure it may be said that he could not know that what he was doing was wrong. … What is meant by wrong is wrong having regard to everyday standards of reasonable people.

- The onus of proving the defence according to these tests is on the accused on the balance of probabilities. In determining the issue I cannot reject the unanimous medical evidence of Drs Furst and Samuels, which I will summarise shortly, in the absence of other evidence, such as observations of the behaviour of the accused which would cast doubt upon their opinions. There is no evidence of that nature. Rather, all the available evidence of the accused’s conduct in the three months up to the date of the collision, particularly in the 48 hours immediately preceding, her statements and behaviour immediately after the collision and assessments made of her during her involuntary treatment over the ensuing three weeks, strongly support the psychiatrists’ opinions.

- In determining whether I should return a special verdict of not guilty by reason of mental illness, I am required to recognise the legal and practical consequences of such a verdict. It would follow from that verdict that the Court may order (1) that the accused be detained until released by due process of law or (2) that she be released either unconditionally or subject to conditions fixed by the Court.

- As to the second of these alternatives, the Court would not make an order for release unless satisfied on the balance of probabilities that the safety of members of the public would not be endangered. As to the first alternative, if I should order that the accused be detained until released by due process of law, she would become a forensic patient pursuant to s 42 of the Mental Health (Forensic Provisions) Act.

- Under s 44 of that Act the Mental Health Review Tribunal would be required to review the accused’s case as soon as practicable. For the purposes of such a review, the Tribunal would be constituted by the President or a Deputy President, who must be a current or former judge or a person qualified to be appointed a judge, plus a psychiatrist and one other person with suitable qualifications and experience. Under s 43 of the Mental Health (Forensic Provisions) Act the Tribunal could order the release of the accused only if satisfied on evidence available to it that:

(a) the safety of the patient or any member of the public will not be seriously endangered by the patient’s release, and

(b) other care of a less restrictive kind, that is consistent with safe and effective care, is appropriate and reasonably available to the patient or that the patient does not require care.

- Before ordering her release, the Tribunal would be required to notify the Minister for Health and the Attorney General and allow them an opportunity to make submissions. If release on conditions were to be ordered by the Tribunal, breach of those conditions thereafter would empower the Tribunal to order apprehension of the accused and her return to psychiatric care on an involuntary basis in detention. Likewise, if the accused’s psychiatric condition should deteriorate after release by order of the Tribunal, and if she should become a serious danger to others, a further order of apprehension and detention would be made by the Tribunal.

- If the Tribunal should not order the accused’s release it would be required to conduct further reviews every six months during continued detention, subject to exceptions under s 46 of the Act.

- The accused’s history of mental illness dates back to 2002 when she was 33 years old. She had been educated to Higher School Certificate level and was apparently a capable student. On leaving school she worked as a journalist and in related fields for over ten years. The history she gave to Dr Furst was of an initial mental breakdown in 2002, including symptoms of severe depression and anxiety. Notwithstanding that episode, the accused was able to resume work and tertiary study in digital screen production and media at Lismore.

- From mid-2012 the accused suffered recurrent episodes of manic, delusional and paranoid behaviour. The first five of these, as documented in medical records, resulted in her being admitted to a mental health unit, the Tweed Valley Clinic, for periods of about three weeks each time. The first admission was a result of manic and disinhibited behaviour including conflict with neighbours and running naked in the streets.

- There were further admissions in mid-2014, February 2015, April 2015 and later in 2015. As these episodes recurred they came to be characterised by paranoid delusions and psychosis as well as mania and sleeplessness. On each admission the accused responded to medication and was able to be discharged but there was recurrent failure on her part to adhere to medication upon release. Also, in between these episodes she continued to use cannabis. In September 2017 the accused told Dr Furst that she had smoked 1 to 2 grams of cannabis per day for 15 to 20 years.

- At the Tweed Valley Clinic in the period 2010-2015 the diagnosis made was of bipolar affective disorder, although Dr Furst considers upon review of the records that her “well systematised delusions” make it likely that she had a schizoaffective disorder by mid-2015.

- From October 2015 the accused commenced to be admitted to the Adult Mental Health Unit at Lismore Base Hospital for her periodic episodes of psychiatric disorder. She was there for a week in October 2015, two weeks in June to July 2016 and two more weeks in September to October 2016. Each time she was affected by paranoid delusions mainly concerning a neighbour. She was acutely psychotic with pressured speech. On each occasion she responded to medication and was discharged but non-compliance with her medication regime was reported in connection with each new episode.

- From early October 2016 Ms Shegog, a resident of Lismore, allowed the accused to occupy a caravan located on her property at the rear of her house. The accused’s behaviour from then, that is October 2016 through to early January 2017, demonstrated ongoing mental disturbance. She sent a stream of long argumentative text messages to Ms Shegog, reflecting bizarre preoccupations with a television aerial with her insistence on maintaining her own privacy, with a rental bond and so on. The accused told Ms Shegog that she suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder and that she was not taking the medication provided to her because it was for schizophrenia which she considered she did not have.

- On 4 January 2017 whilst Ms Shegog was absent from her home the accused rearranged the furniture in it. When Ms Shegog returned to the house she found it in disarray with the accused sitting on the floor in the middle of the lounge room saying she was being psychically attacked. Early the next morning, that is 5 January, the accused used the shower in Ms Shegog’s house and was heard screaming and shouting randomly and loudly from the bathroom. At this time Ms Shegog inspected the caravan occupied by the accused and found it had been physically damaged. A screen door and a cupboard door had been ripped off their hinges, a light fitting pulled out and curtains torn down. Ms Shegog told the accused that she was going to call the mental health team and she did so. Mental health staff arrived later in the day at about 4.00 pm but by then the accused had left the property.

- She drove to the Gold Coast at some time on 5 January 2017. At 1.15 the next morning, that is in the very early hours of Friday 6 January 2017, the accused entered the Sofitel Hotel in Broadbeach and sought a room. The night supervisor was so concerned about her erratic speech and behaviour that he advised her nothing was available. The accused complained of breathing difficulty and heart palpitations so the night supervisor called an ambulance. An ambulance arrived promptly, within 10 to 15 minutes. The accused was aggressive and unco-operative in a physical examination. She rejected the attention of the paramedics and went to her car. They tried to dissuade her from driving but she accelerated away aggressively.

- The ambulance officers reported to their base and requested that Queensland Police be notified of the behaviour and description of the accused and her car. The evidence does not reveal whether such notification was given or, if so, whether any action was taken to try to locate the accused. The next that the evidence reveals of her movements is the observations of the various witnesses who saw her driving between Byron Bay and the Cudgera Creek Road overpass between 8.20 and 8.30 am on Friday 6 January.

- Dr Furst considered all available information as recounted above as well as the records of the accused’s admissions to the Tweed Valley Clinic as an involuntary patient for three weeks following the collision. His summary of what the accused told medical staff during that admission is as follows:

She said that she’d been unwell for about seven days and had not slept at all. She told staff that she felt her body and car were possessed by ‘black magic’ and the car was driving faster than it could physically go. She said that she was ‘possessed’ before crashing the car into the motorbike. She said that they were controlling her body and mind and putting the thoughts into her brain. She said that the voices and the motorbike rider was Ewan McGregor. She became convinced that she would die over the previous three days because of her possession. She said the voices talked to her and about her in the form of four male voices.

- The accused recounted to medical staff, during that admission from 6 January until 27 January 2017, her perception of persecution by neighbours over the years, involving physical attacks and stealing. The diagnosis made by psychiatric staff at that time was summarised by Dr Furst in these terms:

[M]ania with psychotic features and/or schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder in the context of medications non‑adherence and ongoing cannabis consumption, which led to erratic and disorganised behaviour.

- Dr Furst noted that the accused’s symptoms improved rapidly with medication and that she was discharged into police custody on 27 January 2017. During her remand in custody since then the accused continued intermittently to experience some grandiose beliefs and delusions for about the first five weeks but improved steadily, including with respect to insight into her condition.

- By April 2017 she was considered by Justice Health psychiatric staff sufficiently improved and stable to be moved from the Mental Health Unit within the prison to the main wing. She has since been detained there awaiting trial.

- Dr Furst examined the accused in September 2017. His opinion, based upon all of the circumstances recounted in these reasons and his examination of medical records and an interview with the accused, is as follows:

Ms Fraser presented as a 48-year-old single female who has been impaired by a relatively severe mental illness in the form of schizoaffective disorder, the differential diagnosis being one of bipolar affective disorder, both of which have been recognised at law as diseases of the mind.

She was suffering from an acute episode of mania with psychotic features at the time of the alleged offence in question before the Court in January 2017. She had not slept for several days and had been disorganised in her behaviour, including driving to the Gold Coast for no apparent reason, calling an ambulance and presenting in a confused manner the night before the offence. She was paranoid and grandiose in her thinking. She experienced hallucinations that were apparently directing her actions and fed into her delusions.

Unfortunately, Ms Fraser developed overwhelming delusions about souls being possessed, including her own, and was compelled by her delusions and ‘voices’ [auditory hallucinations] she was hearing to drive to the Tweed Bridge as fast as she could in order to save herself and other people’s souls. I understand that she was driving in a dangerous manner, at around 180km/h.

Her alleged actions of killing the motorcyclist may have been driven by her delusional compulsion to get the Tweed Bridge and/or driven by a belief that the motorcycle rider was Ewan McGregor and that his soul would die otherwise. In either case, she was suffering from a defect of reason in the form of her delusions and as a product of her disease of the mind such that she was unable to reason about the wrongfulness of her actions with a moderate degree of sense or composure.

- Dr Samuels considered the same history from the medical records and also examined the accused by way of an interview on audio-visual link to the prison on 24 November 2017. He had regard to the circumstances generally of the accused’s background and of the accident as I have recounted them. Dr Samuels expressed this opinion in his report of 24 November 2017:

It is my view that Ms Fraser was suffering from a disease of the mind, namely a psychotic illness with paranoid delusions and hallucinations. She suffered from a defect of reason at the time of the offence and acted on these delusions believing that he had to drive at high speed to the Tweed River Bridge in order to save the lives of an actor and other people possessed by the devil.

I believe that her psychotic state prevented her from knowing the nature and quality of the act and that she did not know what she was doing was wrong and genuinely believed that she was saving the life of Ewan McGregor and others.

- Dr Samuels recorded differences between the accused’s statements to him regarding her intent and statements she made on that subject to police and medical staff at the hospital on the day of collision. I do not regard her statements regarding specific intent on either occasion as important to what I have to determine. That is because on all of the above evidence I consider the mental illness defence as established and that the accused does not bear criminal responsibility at law for her voluntary act of driving into Mr Moran’s motorcycle. It is unnecessary to determine what (if any) specific intent may be attributed to her.

- I am satisfied on the balance of probabilities that at the time of the collision the accused laboured under such a defect of reason from the disease of her mind (which Drs Furst and Samuels have identified) that she did not know the quality and nature of what she was doing. She did not know that she was driving her vehicle at an excessive and dangerous speed and in a lethal manner towards Mr Moran’s motorcycle. She was deluded that she and the vehicle were being caused to speed and to manoeuvre as occurred. If and to the extent that she had any appreciation of what she was doing regarding the manner of the car being driven, any understanding that it was wrong was beyond her in her state of psychotic delusion. She was under the hallucinatory belief that she was possessed by some personal force such that she lacked control in the choice of her actions.

- The consequence is that there must be an order that the accused be detained in the place of her present remand until released by due process of law. I have been asked by her counsel, Mr Watts, to consider ordering a report on the accused’s present psychiatric state and adjourning final disposition of the case, with a view to ordering her conditional release if this would be consistent with the accused’s proper care and with public safety in her current psychiatric state. I am not satisfied that taking such a course would lead to any quicker determination than would result from the order which I propose, pursuant to which the Mental Health Review Tribunal will make a determination concerning release, conditional or unconditional, as soon as practicable.

- Also, I am not satisfied that I would be as well-placed to make a determination about release as would the Tribunal, having regard to its composition, the experience and expertise of its members and the resources and means available to it to obtain all relevant information on the accused’s current mental state and prognosis.

- I should not leave the case without recording the Court’s recognition of the depth of the tragedy this event has involved for the Northern Rivers community and in particular for the late Mr Moran’s family. Mr Moran was 61 years old. He lived in the Byron Bay district and ran a farm. He is survived by his wife Bronwyn who shared a happy life with him and has been left with a struggle, both emotionally and in managing what were the joint endeavours and affairs of herself and Mr Moran. Mr Moran leaves two sons and a daughter from an earlier relationship. They are in their late 20s and 30s. They were close to their father and are devastated by the loss. There are now two grandchildren and there is great sadness that they will grow up not knowing a man who was much loved by his family.

- The difficulties of managing mental illness in the community are enormous. Humane care for psychiatric patients requires that involuntary confinement should be imposed cautiously and with some restraint. Mental health professionals have the agonising task of trying to secure the safety of the community whilst balancing that objective against the potentially counterproductive effects of overuse of involuntary commitment of patients to care in detention.

- As this case has shown, a patient who is episodically psychotic may not exhibit any significant tendency to violence and may not present as a high risk to public safety, but yet may commit a lethal act from behind the wheel of a car. The accused, now in a stable, medicated condition, has expressed in a letter to the Court her deep remorse for what occurred.

- The potential for tragedy from mental illness is ever-present in a community of human beings and continues so despite collective best endeavours to treat psychiatric patients optimally and to minimise risk. The risk has been realised in this case in a way that falls very hard on the loved ones of Mr Moran. This community no doubt strives to understand their pain and to share it.

Orders

- The orders of the Court are:

- Verdict of not guilty by reason of mental illness.

- Order that pursuant to s 39 of the Mental Health (Forensic Provisions) Act Vanessa Fraser be detained in the place wherein she has until now been remanded in custody, or in such other place as the Mental Health Review Tribunal may hereafter direct until she is released by due process of law.

- The Registrar of the Court is to notify the Attorney General, the Minister for Health and the Mental Health Review Tribunal as soon as practicable of these orders and to provide each of them with a copy of:

- the reasons of the trial judge given this day, 23 October 2018;

- the report of Dr Furst, dated 17 September 2017, marked exhibit 1 in the trial;

- exhibit A in the trial incorporating the report of Dr Samuels, dated 24 November 2017 and

- exhibit 2 in the trial, being a letter signed by the accused, dated 26 August 2018.