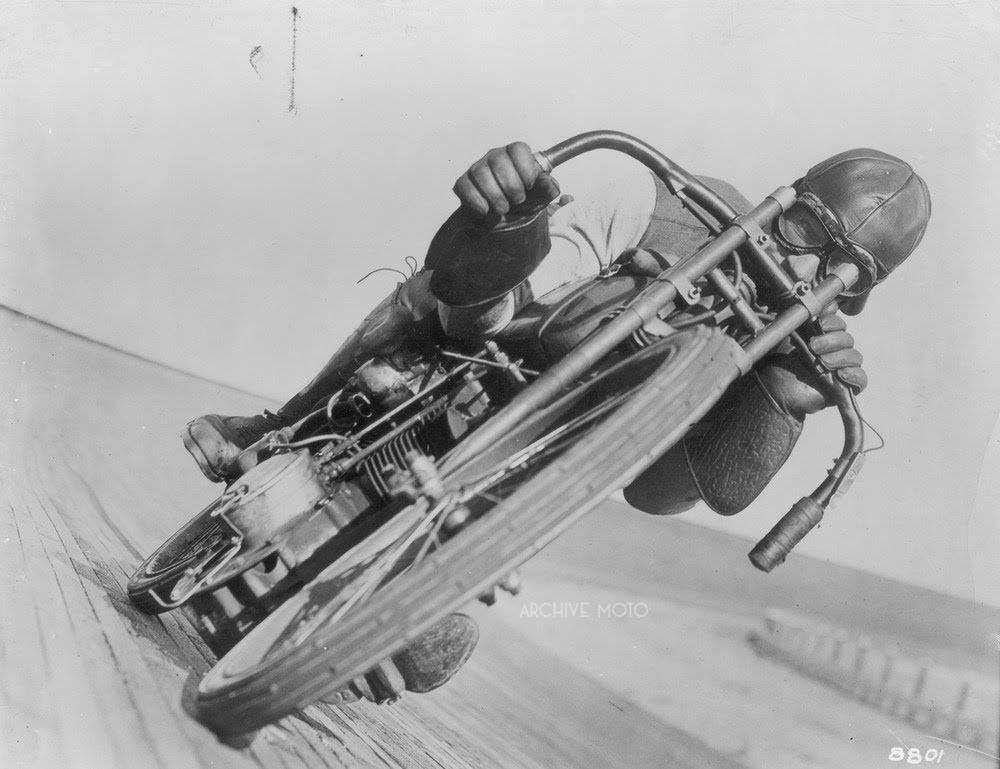

It’s summer in 1915, and freshly famous motorcycle racer Otto Walker powers across the finish line at the Dodge City 300 event to claim victory. Harley-Davidson is on top of the world, and a new motorcycling legend has been born; a legendary brand that is still a house-hold name almost 110 years later. It truly seems like Harley’s fortunes are going to be golden for ever and ever.

Now it’s 1981, and an overweight, middle-aged, midwestern dentist has pulled over to the side of the interstate because his AMF-era Sportster has been badly misbehaving. With handling like a boat and a raft of other irritating issues plaguing the new bike, he’s swearing out loud about wasting his money on a vehicle that was meant to be a present to himself for putting up with all those screaming kids and needy patients. Now the bike stalls to a stop after refusing to idle.

Screaming, he leans the bike over to deploy the side stand only to find that the engine’s vibrations have managed to loosen the bolts—so that it’s now hanging limply beneath the bike. Caught off guard by the malfunction, he and the bike tumble over sideways to the amusement of the passing four-wheeled traffic. But how did such a promising company squander such a commanding position and reach the absolute depths of brand hatred? And can they claw their way back again? Let’s find out.

A Brief History of Harley-Davidson

Thanks in large part to WWI, Harley went into the Great Depression as the world’s biggest motorcycle manufacturer. The growth of the company in these years is nothing short of spectacular; from building their first factory in 1906 to ruling the world 14 years later is an amazing feat in anyone’s books. Clearly they were doing something right. Scrub that. They were damn well doing everything right.

And while the depression did kick Harley’s sales to the curb in the early ‘30s, they still managed to create an industrial power plant branch of the business, and they opened a new plant in Japan to boot. Then came the ‘Knucklehead’ engine of 1936. Again, a name that would be written into the motorcycling history books. And soon after, WWII would see more lucrative military orders flooding them with plenty of work—making 90,000 units of their WL and WLA models.

One of only two American motorcycle manufacturers to survive the war, their run of good luck continued into the 1950s. This was in no small part due to more military orders for the Korean war and the general economic boom America enjoyed thanks to massive profits from WWII (without the corresponding economic hit that many of her allies took, thanks to all that bombing and pillaging).

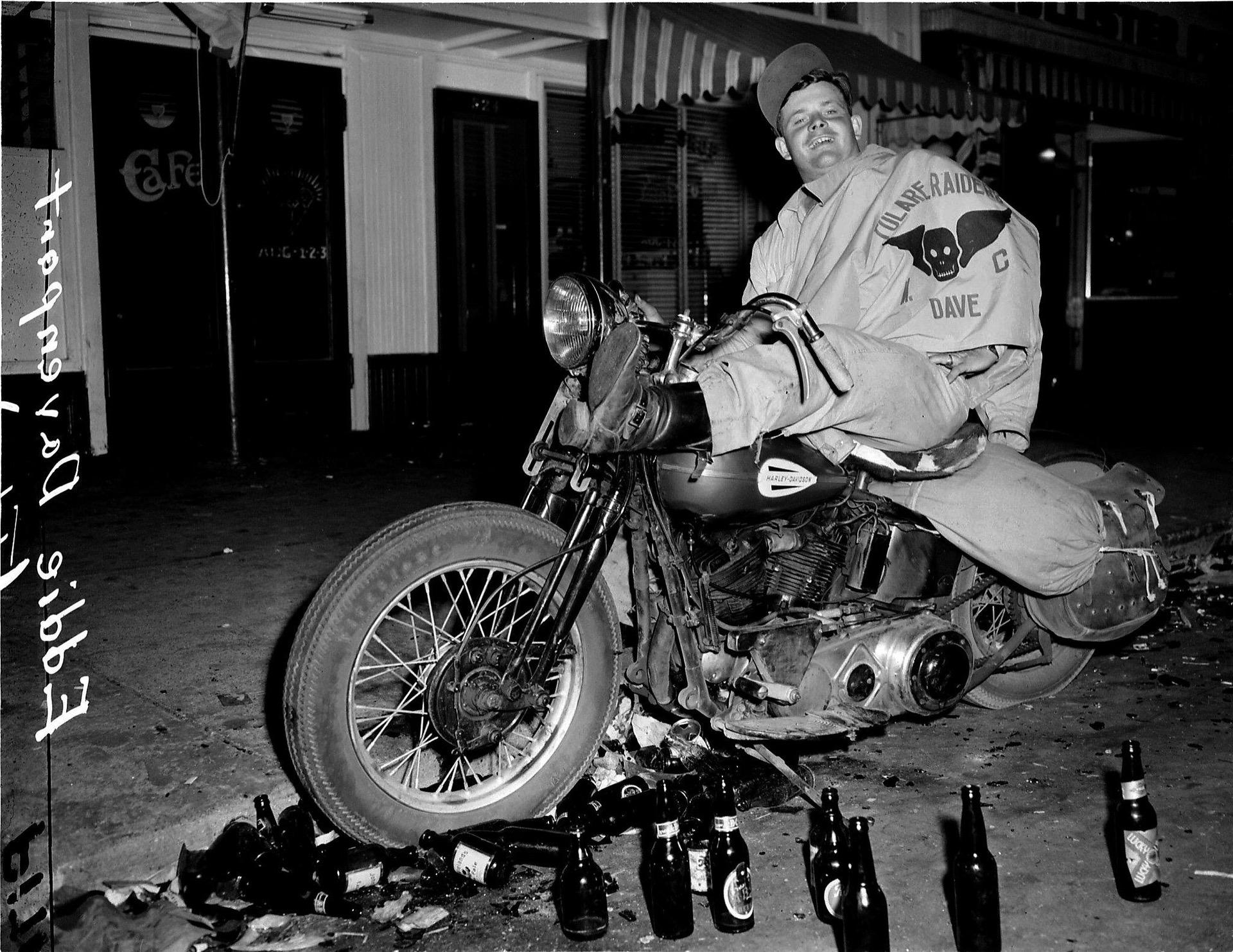

So at 40-plus-years and still going strong, it now seemed as if Harley was unstoppable. Add to this fact the emergence of these new ‘bikers’ types.

With a bunch of ex-service men and women now back home from the war and looking for some kicks to equal fighting the Germans, the availability of cheap ex-army Harleys and their pockets full of cash, many of them took to hanging out on weekends with each other and riding motorcycles for something to do. Not only did Harley have a legendary brand, they now also had a grassroots social movement behind them. Talk about gilding the lily.

Of course, the 50s and 60s in America also saw the rise of corporate culture. Companies that were previously run by families with the care and attention that only obsessive fanatics can provide now saw themselves being answerable to shareholders and the almighty dollar.

Harley-Davidson, in an attempt to make more while spending less, began on a program of ‘diversification’. The early move here was Harley’s purchase of fifty percent of Italian aircraft maker Aermacchi’s motorcycle division, no doubt in an attempt to quickly broaden their range of bikes and appeal to a wider range of customers.

Mucho corporate shenanigans ensued, and in 1969, the whole company was sold to the American Machine and Foundry company of White Plains, New York. AMF management quickly began ‘rationalising’ the business, mostly by frantically cutting corners and firing staff.

The results weren’t anywhere near what the AMF management had hoped for. Instead they now had expensive, poorly made, and under-performing bikes—along with a massive onslaught from the Japanese manufacturers to deal with.

Like discovering a ninja in your house during a large bout of food poisoning, Harley was well and truly caught with their pants down. Unsurprisingly, they were nudging bankruptcy by the early 1970s and existing month-to-month. It’s from this era that the “Hardly Able Son” name-calling originated. Quality is the last thing on your mind when you are living hand-to-mouth.

Flogging the dead hog for the next 10 years while skipping from one disaster to another, their survival was in no doubt due to their lasting legacy and was helped by things like the movie Easy Rider locking their fame even further into America’s globally-dominant pop culture.

Besides, that non-American, overseas-living, aspiring biker guy who so badly wanted a Harley didn’t know any different. How could a legend like the all-American Harley-Davidson not live up to his expectations?

A lifeline was thrown to the brand in 1981, when a group of 13 investors led by Vaughn Beals and Willie G. Davidson bought the smoking wreck of the former behemoth for $80 million. This new age of Harley was also helped by the Reagan administration agreeing to add tariffs to certain Japanese bikes. So much for the Republican’s ‘small government’ and Laissez-faire economics, I guess.

The freshly minted Harley board launched a renaissance program that revolved around reviving past glory models in conjunction with a complete overhaul of the company to ensure that its manufacturing processes, management, and designs were all up to scratch.

Of course, the rejuvenation wouldn’t happen overnight. The company would suffer under damage done by AMF for many decades. Indeed, they still have to battle the bad press to this day. And they were by no means out of the woods yet—not by a long shot.

While the successful introduction of the Fat Boy, Dyna, and Softail models no doubt helped them greatly, the last 30 years would also see them buy—and then dump—the Buell sport bike brand, do something very similar with MV Agusta, start and then cancel many overseas production operations (including ones in India and Australia), be accused of stock price manipulation, battle the Global Financial Crisis, weather claims of ‘death wobbles’ on various models (including police bikes) and struggle through battles with unions. And dare I mention the V-Rod? Best not, I think.

Today, Harley-Davidson is still a brand that seems to be looking back at past glories while trying to find its way into the future. The revealing of their LiveWire electric motorcycle was both impressive and also supremely confusing.

While its looks were bang-on, and their bravery in pushing the envelope could be directly linked back to those bold decisions that led to Otto Walker’s wins in 1915, it also left an army of fans scratching their heads, wondering why their beloved Harley would stray so far from the bikes that made them famous. An electric Harley? That’s sacrilege!

The same could be said for the brand’s el-cheapo ‘Street 500’ model, which was tarnished by sub-par build quality and a severe case of trying to pander to the masses while losing sight of the brand’s own core values. And as for the Pan America, the jury is probably still out on the bike—but was anyone really screaming out for a Harley Davidson off-roader? Only time will tell.

To close the discussion, I’ll relate a quick story of mine. As someone who is pretty lukewarm on the whole Harley thing, I caught up with a friend and bike builder recently who’d just got his box-of-spare-parts 1960s Harley Sportster on the road again (pictured above).

Expecting to feel nothing, the bike blew me away almost instantly; stripped of its excesses and resprayed in bright orange, I wanted to make an offer to him to buy it there and then. Low, clean, waif-like and with an undeniable ‘50s/’60s bad-boy racer vibe, the thing was a real testament to what Harley can achieve when they hit their straps and keep their eyes on the ball.

Dear ghosts of William S. Harley and Arthur Davidson; more of this if you are listening, please.