A Short History On The Legendary Man

If you were a kid planted in front of the TV in the 1980s, basking in the glow of the cathode rays as they showed you a young rider rising quickly through the ranks of American Superbike racing, you have obviously heard of Wayne Rainey. You know the fierce battles, the smoothness and courage showed in his push to win, and the three back-to-back world championships in the Grand Prix World Championship (GPWC) of Superbikes, the predecessor to MotoGP.

For those not aware, Wayne Wesley Rainey, born in 1960, was what could generously be called a prodigy. By 1981, he was racing in the AMA Grand National Championship, and was ranked the 15th best dirt track racer in the USA. He changed over to 250cc road racing in 1982 and was picked up by Kawasaki for the AMA Superbike championship that year, partnering with the defending National Champion Eddie Lawson.

During the 1987 season, riding for American Honda in the AMA Superbike series, one of the most famous rivalries in all of superbike racing started. It was the year that Wayne Rainey met Kevin Schwantz. It was the year that they would both leap out in front of the field on the first few laps, and then race wheel to wheel for the entirety of the race, often separated by less than a second, and when one pulled out ahead, it was only a few seconds and they ate up tire life doing so.

Both moved up to the GPWC in the new 500cc class in 1988, with Wayne rejoining Team Roberts Yamaha who he had a one-season stint with in the mid-80s, and Kevin going to the factory Suzuki team. Their rivalry also came with them, with the two fighting wheel to wheel in the first 500cc race at the British Grand Prix at Donington Park, which Wayne won. The two also took part in the inaugural Suzuka 8 Hours Endurance Race, with Team Roberts winning that event.

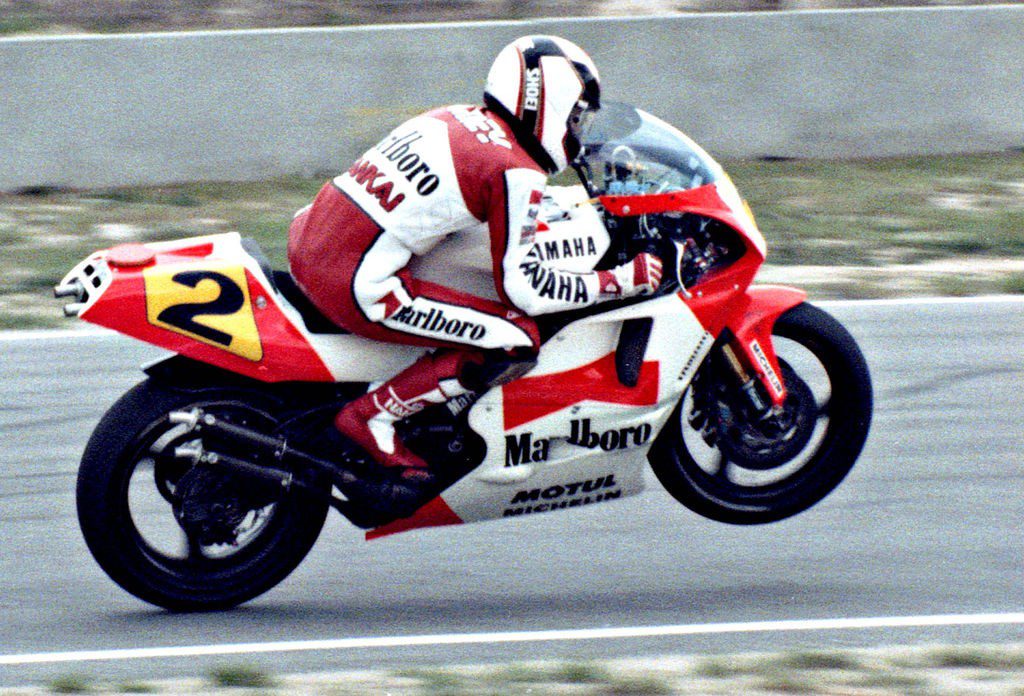

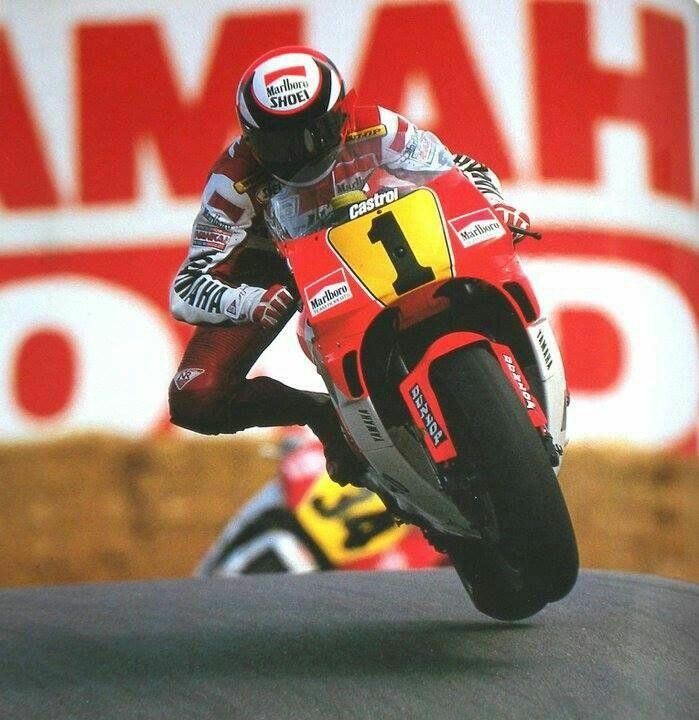

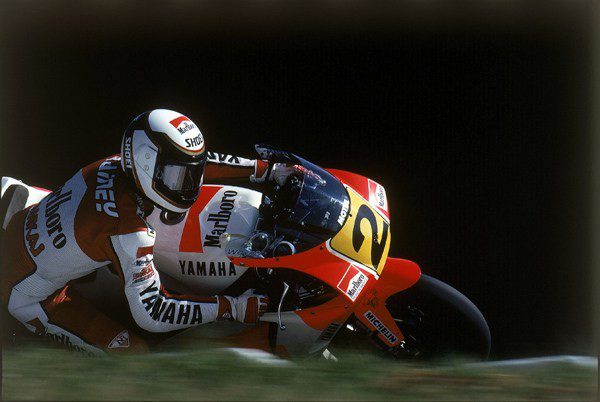

1989 saw continued success for Wayne, as he achieved a podium at every race, sometimes beating out names like Mick Doohan, Roger Burnett, and teammate Kevin Magee. In 1990, Wayne finally found the perfect form, the perfect setup, the perfect sponsors, and the perfect team to back him (by staying with Team Roberts Yamaha). Riding the legendary 1990 Yamaha YZR500, he won the 500cc GPWC title. And did so again in 1991, including winning the round in front of his hometown Monterey crowd at Laguna Seca. He continued in his championship stride and despite a resurgent Kevin Schwantz pushing him to his limits, won the title for the third time on the trot in 1992.

However, that surge from Kevin would come back to bite both in the 1993 season. Wayne was getting pressured hard by Kevin, and was leading by only 11 points in the championship, making each race win and podium count.

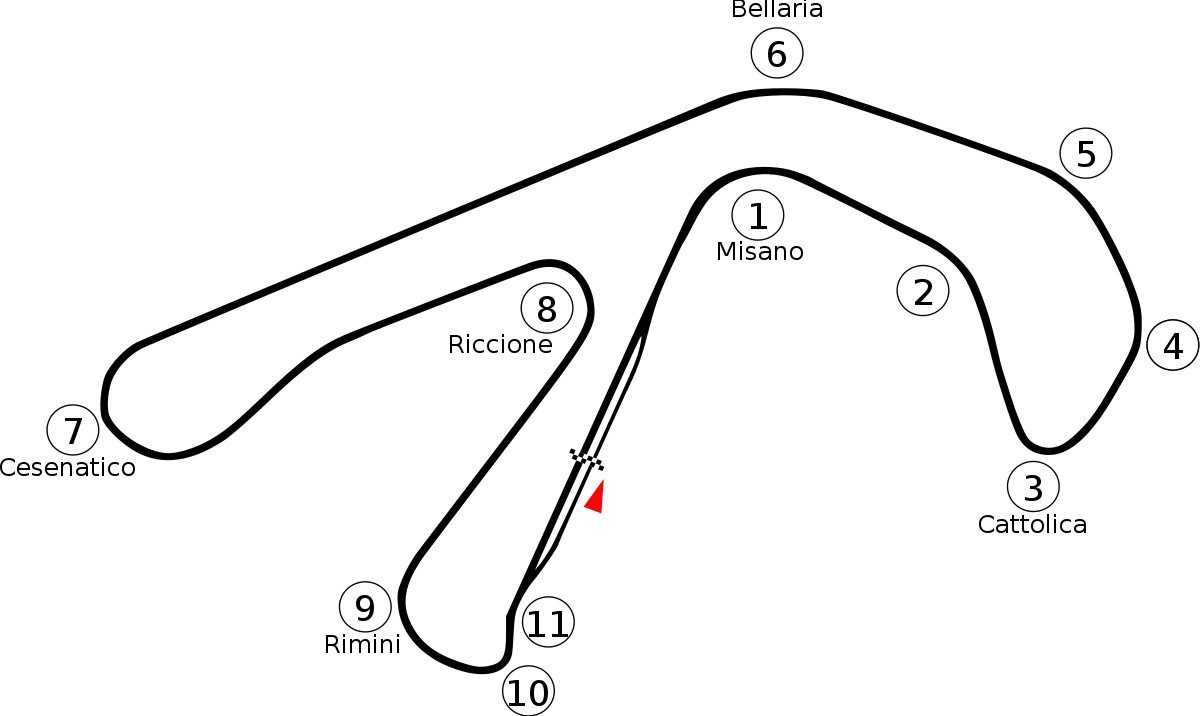

At the Italian Grand Prix at Misano, the same circuit that would later be named after the late Marco Simoncelli, Wayne was leading the race when he lost the bike, slid out into a lowside, and critically hit the curbing at the side of the track, which tossed him end over end into a gravel trap. When it had all come to a stop, he tried to get up, but found that he could only really move his arms, and his legs weren’t responding. By hitting that curbing and landing at an awkward angle, he had severed his spinal cord.

Sitting Down With The Legend

I want to start off this section by once again thanking Mr. Wayne Rainey, during the leadup to the MotoAmerica Laguna Seca weekend, for putting aside time in his busy schedule to have what I would label as a Powersports fan’s dream interview. I personally have watched all forms of racing from Formula 1 to International FIA GT, the old GT1 endurance races, Le Mans, you name it, I was–and always will be–a fan of it.

Note: Content has been edited for clarity and conciseness.

Simon Bertram: Mr. Rainey, firstly, let me thank you for setting aside the time to have this interview. It’s a bit of a dream come true for me!

Wayne Rainey: No problem at all, happy to help.

SB: While it was 30 years ago, something I’ve always wondered about was what sticks with a champion after they retire or are forced to retire from sports. What do you recall from your Laguna Seca win in 1991?

WR: Wow, that’s a bit of a hard question to answer, because as you said, it was 30 years ago. I don’t remember every turn, every lap, but what I do have are awesome memories. The bike was great, perfectly tuned to the track and my rhythm. Of course, it was also my home crowd, so feeling that energy was amazing.

It was one of my most special races. These were the days of riders that rode monsters, bikes that had no traction control, no anti-lock brakes, nothing other than rider skill. And being able to hear the roar of the crowd cheering, even over the sound of the bike, made it special. As one of the few American stops that the Grand Prix made in the United States, it was super important to me to win that race, in front of family and friends, in front of my hometown crowd.

You know that feeling you get when you nail a corner on a bike just right or flow through a technical section of a track perfectly? That was the feeling I had in my chest as I crossed the finish line first.

SB: I have had that feeling, actually, the first time I took a corner on my own bike on the road where it just felt perfect, that little buzz in the chest of “yeah, I’m doing this!”

Now, as you mentioned that Laguna Seca is your home track and, rightly so, very special, are there any other tracks that you raced on that hold special memories for you? Best battles, perfect laps, the like…

WR: Well, I took every race track as its own challenge, and I love the challenge of every racetrack. But, there were a few that were very special to me, and not in the way that most people would think.

I spoke with someone earlier today about the race at Assen, Holland, in ‘91. I ended up getting second place to Kevin Schwantz, I still think about it to this day.

About a third of the way in, it started to rain. Back then, they stopped the race instead of having a spare bike setup with wet tires. In those days, you would carry the time ahead or behind the rider in front and behind, and Kevin was leading me by about half a second. So, when we restarted the race, he already had a half a second lead on me, so that meant by the end of the race, not only did I have to beat Kevin, but I had to beat him by half a second.

I had pulled out a good lead on Kevin through the race, but at the start of the last lap, my pit board said “+0.0 SCHWANTZ L1.” I had to gain that half a second back, and put together a lap that was honestly probably the best lap of my entire career. I pulled over a second on him going into the last turn.

As I flicked it in there on the brakes, I pushed the front out. I couldn’t risk it so close to the end, so I straightened it up, went straight off the track, over the gravel trap, and as I moved to get back on track, I had to put my left foot down to lean away from a grass hedge that divided the pit road from the racetrack.

As soon as I was back on the track, I started to accelerate. I could see the start/finish line, and Schwantz passed me right as we both crossed the line. So, after all that, he still barely beat me. What I really remember, however, is that even after doing all that, Kevin got the lap record on that lap, which lasted for another, if I remember, 10 years, until they changed the track.

SB: What other tracks hold special memories for you?

Another track I remember is Misano, the same track where I raced my last race, on the Adriatic Coast in Italy. It was a track that I could race the 500 much like I raced flat track back in the States, and had a series of four left-hand turns (Turns 3 to 6 in the above image) that you started out in second gear, short-shift to third, it opens up, shift to fourth, you lean it in… you could make one big arc out of the four of them.

In 1990, I was leading the race, Mick Doohan was in second. I forget how much of a lead I had, but in getting so far ahead, I chunked my rear tire. Back then, you never came in to change a tire but Mick had caught me and passed me, and I decided to pull into the pits. My team came over all nonchalant like “oh, the bike is broken?” to which I reply: “I need another rear tire!” They say “What?!” And I go “GIVE. ME. ANOTHER. REAR. TIRE! I’m going back out!” So they grabbed John Kocinski’s spare wheel, changed out the sprocket, and threw it on my bike.

As I was exiting pit road, Mick was now lapping me. I got the tire warmed up, chased Mick down, caught him, and passed him. I then had to ride as hard as I could to try to catch the pack. In the end, I crossed the line in 9th place. That was another racetrack (and another race) that I didn’t win, but it’s a memory that I’ll always keep.

SB: It’s well documented that you and Kevin Schwanz had a fierce rivalry in the 1987 American Superbike championship. Do you think that having that type of rider pushing you to be your best, race after race, effectively made you into the champion you were to become?

WR: I can tell you that the rivalry was real, and yes, Kevin pushed me in a way that no other rider did. It was possibly because there was a bit of a dislike for each other, but it wasn’t a feeling of hatred.

I really didn’t realize how much the rivalry meant to me, really, until I stopped racing. When I had time afterward to reflect back, and to see what happened to him after my retirement. The thing that was special about Kevin was that I could focus on three or four other guys (Mick Doohan, Eddie Lawson, John Kocinski) and not focus as much on Kevin. Or, I could focus just on Kevin if it was just us two racing each other, and that took care of the rest of the field that was behind him.

We both raced each other like we wanted to win, we both wanted to beat each other like no one else out there. It’s been almost 30 years now since we last raced each other, and we’re still not great friends, but there is that respect for each other.

SB: Rainey Curve at Laguna Seca: I’ve driven it many times in sim racing, and it’s always a real pain to set up for, having to recover from left to right across the track right after the corkscrew… What do you think of having one of the most deceptively difficult corners on the track named after you?

WR: You touched on it almost perfectly there, because on a bike, when you come out of the bottom of the corkscrew, everything wants to push towards the outside of the corner. Your bike wants to go that way, the hill is canted that way, and you have to really put in the effort to bring it back over to the right.

What was important on the bikes, especially back then, was to get to the right enough so that when you braked and leaned, you got on the clean line. Brake a moment too late, you’re out wide, on the dust and sand, and it’s really tricky to pull the bike back to the racing line, and you miss the apex. Brake too early or lean too hard, and you clip the apex early, again sending you out wide into the slippery stuff.

But when you got it just right, the bike would hook up like you wouldn’t believe, and you could disappear down the track. It’s one of those curves that has no margin for error, you need to get it right every time, or it could literally lose you the race. Of course, I’m very honored to have that corner named after me, and whenever MotoAmerica comes back to Laguna Seca, I’ll sometimes go out in the wheelchair in the morning and sweep the corner clean.

SB: Do you remember any words of wisdom that Frank Williams said to you that any young up-and-coming racer should hear? His team is as legendary in Formula 1 as your three championships on the trot are to American superbike racers, and the next generation is always the one that will carry the torch of motorsports forwards.

WR: To make what he said to me make sense, you need to realize how much the crash at Misano affected me. I was 33 years old, at the top of my chosen profession, with a lovely wife, newborn kid, and then suddenly I had no movement below my chest. In a word, it was devastating.

And that’s not to skip the fact that from the moment I was taken to the Misano medical center to getting out of rehab in California was 12 weeks. 6 weeks in a cast that made me miserable, and then 6 weeks learning how to effectively live again. It got pretty dark in those days, and then Frank came over from England to visit.

It was like the curtains had been pulled back. Watching him get out of the car into his wheelchair, and he’s a quadripalegic with only minor movement in one hand, was a turning point. Racing requires a serious bit of ego, and watching him being helped into his chair with an air of dignity and confidence around him, and the way he carried himself despite his disability…

However, there was also a moment of honest truth that changed my whole outlook on life. Frank said to me, “You’re fucked. As soon as you realize that, you’ll start living again.” In the state I was in, I really didn’t understand what he meant. It was after a few months of getting used to my new routine that it dawned on me… although my body is broken, my mind is still there. Frank inspired me to keep going, making each day a push and a success.

SB: I personally watch MotoAmerica Superbike racing, and I have to say I am really happy with the direction it has been, and is continuing, to go. Do you see yourself remaining as one of the heads of the organization for the foreseeable future?

WR: (Wayne laughed for about 10 seconds here) Well, the whole story of how MotoAmerica has blown up always surprises me. By 2015, the AMA Racing association had messed up the rules, killed off classes, and made it very unattractive to manufacturers and sponsors alike. It was actually Dorna, the company that owns MotoGP, that asked me if I would be willing to step in and give the series one last injection of life before they wrote it off.

My partners and I took over and immediately threw out the current rule book. We took the basic rules of World SuperBike for the primary classes, but also proposed new and different classes. Superstock, superbike, minimoto, junior 600cc, all of those classes were expected. We also created the SuperTwins category.

We started out with 3 sanctioned races, no TV, and minimal attendance, and over 7 years we now have 10 sanctioned races, 5 racing classes and the fun classes I mentioned, and worldwide TV coverage. We also created the Hooligan class for supernakeds to race in, the King of the Baggers for bagger cruisers to be raced in, and we’re always looking at what people want to see.

Honestly, the real big draw for me was to revive a series that I myself had come through in my younger days to allow for Americans and Canadians both to have hometown heroes to cheer on, and for talent to be developed that might one day move up to the top tiers of racing, either in MotoGP or World Superbike.

SB: Anything you’d like to add before we wrap up today?

WR: In a strange way, this past year and a half has revitalized motorcycle riding, and racing, in North America. Everyone was feeling too cooped up, and by going out and learning to ride, since a bike is really a one-person vehicle, you could go out on a ride and still follow all the health guidelines. Track days, group rides, motorcycle clubs, it’s all really exciting

And with that interest in riding, we potentially have an entirely new generation of future champions getting their first real taste of what it’s like on two wheels. I am, in fact, much more excited about the future than I was in the past, and I don’t plan on retiring from running MotoAmerica anytime soon. I’ve pulled back because I am getting on a bit. I’m 61, but with the people I know running things as they are, American superbike racing isn’t going anywhere but up.

SB: Once again, thank you so much for your time and insight.

WR: You’re quite welcome!