The global success of George Miller’s Mad Max first installment in 1979 meant a lot for Aussies, young and old. Not only did it prove that we could punch above our weight when it came to motion pictures and storytelling and introduce the world to the new genre of ‘car chase apocalypse’ movies, but it was also a crucial vehicle (pun fully intended) in introducing the world to Aussie culture; and what could be a more important aspect of Antipodean society in the late ‘70s than the Aussie V8?

And while many of my countrymen and women would love to be able to tell you about how the movie also featured some killer Aussie motorcycles alongside the now-famous Ford ‘last of the V8 interceptors’ Falcon XB, the sad fact of the matter is that all you see in the movie was wall-to-wall Kawasakis. So, why was Australia so adept at making cars and not motorcycles?

The sad fact of the matter is a common thread that has been woven throughout Australian manufacturing from its very earliest days. Despite the multitude of dreams Aussies had to make cars and bikes locally, the unavoidable fact of the matter is that the country’s population is not only minuscule, but it’s also as far away from the rest of the world as you can get before you start getting closer again. The upshot is that everything you might need to import to make a vehicle costs a bomb, and your chances of making up the costs you’d wear to get them down here can’t be recouped with local sales because there simply weren’t enough customers to buy the bloody things.

Despite this harsh reality, a handful of ‘never say die’ Aussies decided their backyard sheds could also be motorcycle factories, and despite the palpable complaints of ‘the Misses,’ the history books show that between the turn of the century and the end of World War 2, more than a dozen battlers gave it a red hot go. Here are three of the best.

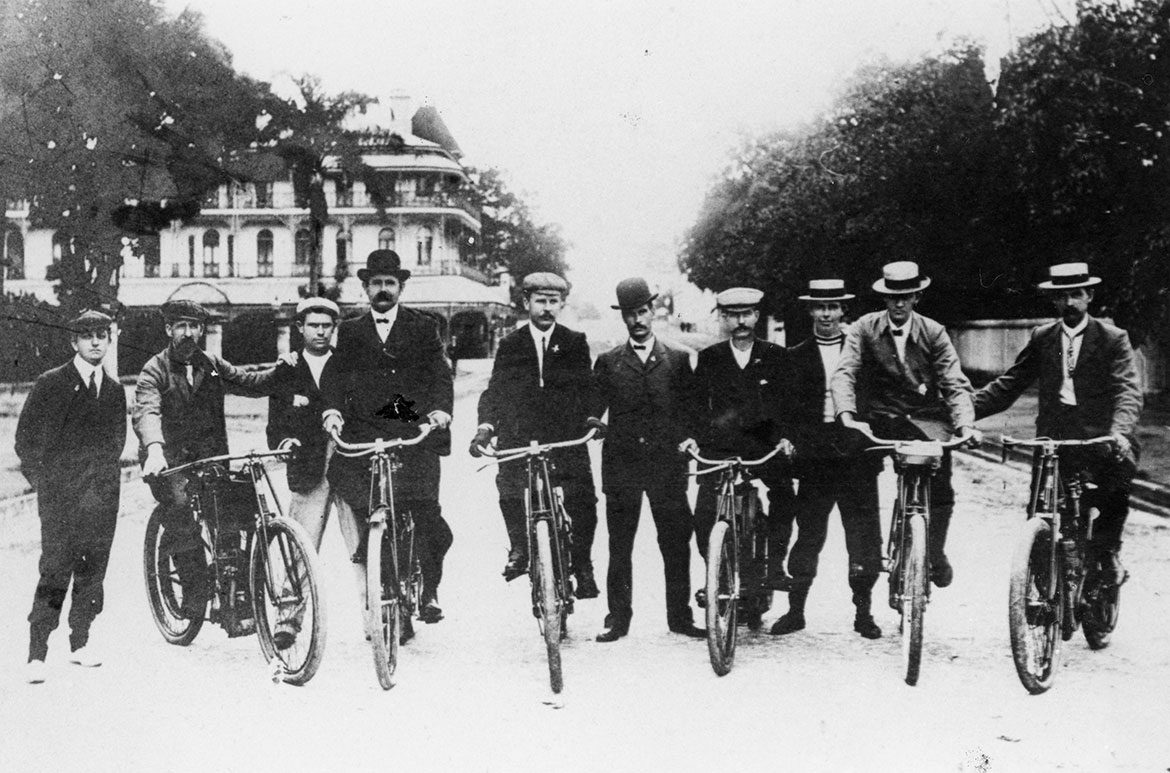

Spencer Motorcycles, Brisbane c. 1906

David Spencer was a Queensland mechanical engineer who was born in England in 1870. Somehow finding time in between fathering nine children, the man used his metalworking skills developed through his job on the Australian railways to build a motorcycle in 1906 in his North Brisbane garage. And in a very Burt Munro-esque fashion, he decided that the best way to test his vehicles was to race them.

Making almost every part of his creations in his shed, his cedar and bronze patterns for engine and drivetrain castings survive to this day and tell a story of an engineer who was supremely capable. ‘Spencer’ branding across the bike’s various levers and reservoirs. The best example of his bikes is shown here – a 475cc single with the encryption ‘No. 3’ on the engine. So impressed were the local police by Spencer’s bikes that they reportedly requested he build them 50 examples. Concerned he wouldn’t be able to deliver on the order, he turned the offer down. But just imagine if he’d somehow manage to make the order a reality? Maybe we’d be talking about Holden, Ford, and Spencer a century later?

Whiting Motorcycles, Melbourne c. 1914

Predating Brough Motorcycles by a good four years and clearly driven by the same ‘top shelf’ motorcycling passions, Saville Whiting was an Australian on an engineering mission. With a deep understanding of the issues surrounding motorcycling’s nascent years, the Melbourne-based designer and engineer solved the challenge of ‘hard’ motorcycle frames with a very four-wheeled solution; leaf springs.

Convinced of the idea’s worth, he named the design ‘spring frame’ and took the bold step of traveling to Mother England in 1914 to sell the idea. And while the local newspapers were smitten, naming the bike ‘the last word in luxury’ for its ride comfort, the outbreak of World War I was also quashing Whiting’s plans for mass production. Returning to Melbourne, he soldiered on to produce three variations in total, a Douglas-engined mule, a J.A.P.-engined second version, and an experimental air-cooled 685 cc V4 engined final swan song in 1919, predating the British V4 Matchless Stirling of 1931 by a full 11 years.

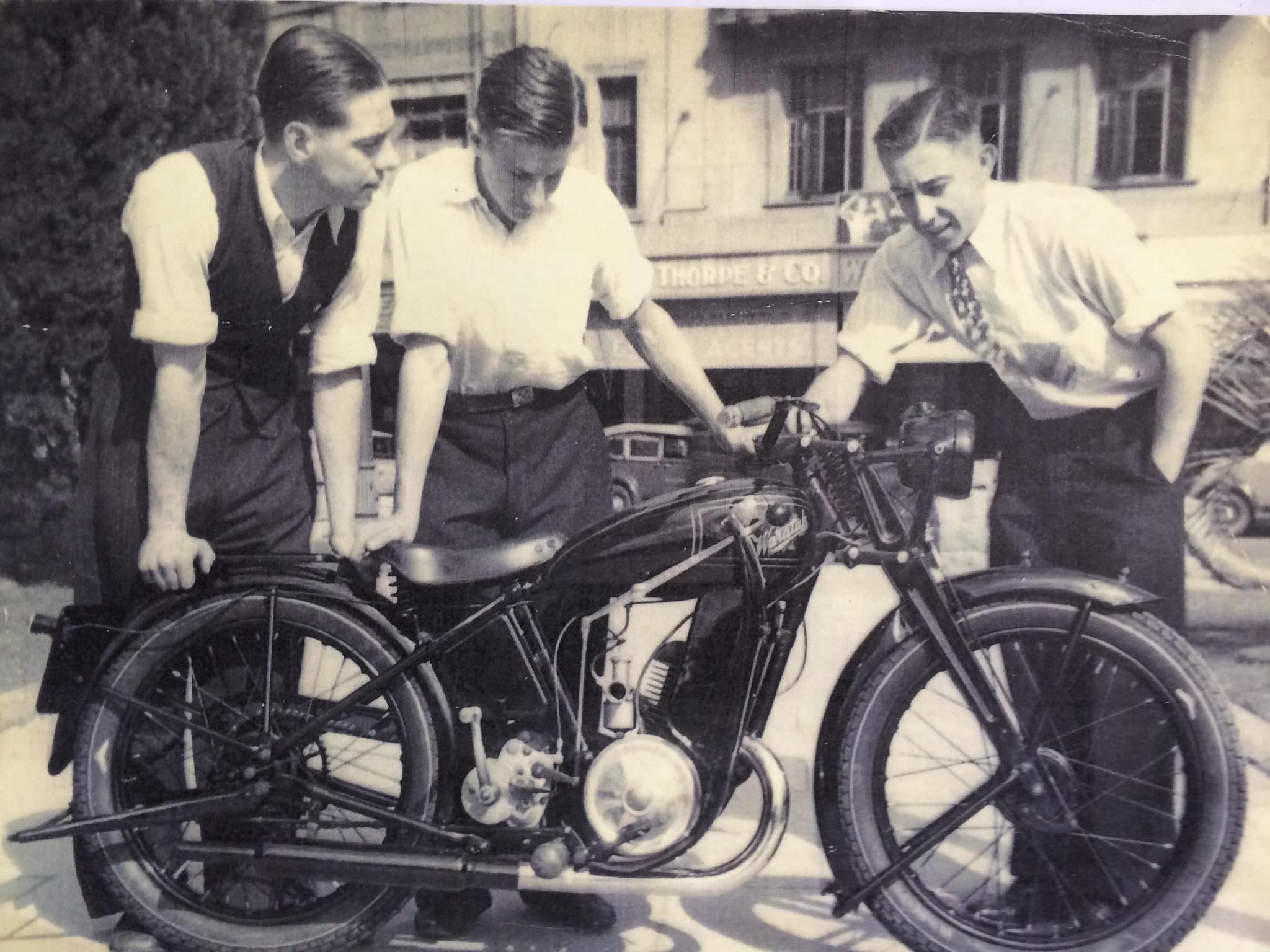

Waratah Motorcycles, Sydney c. 1911

Known as the largest and most successful of all the Australian motorcycle makers, Waratah was founded in 1911 and carried on until its post-war demise in 1951. Starting off as importers, they stand in stark contrast to Spencer and Whiting in their approach to the business and production. Shunning the small, handmade approach, they sold mostly bikes assembled out of pre-existing frames and British engines. This changed to mostly ‘badge engineering’ Norman and Excelsior bikes imported from England after World War II.

While little information remains on them, it’s clear they hold the record for Australia’s longest-running and most successful motorcycle manufacturer, selling Waratah-badged bikes well into the 1950s. And while you may be tempted to downgrade them thanks to their lack of home-grown engineering chops, it’d pay to remember that Holden was also started as an Australian-based ‘body builder’ that used imported General Motors ‘knock down’ componentry and chassis to assemble cars locally.

The irony is that the same post-war boom in car sales that empowered the rise of the cafe racer culture in the UK also saw off the last of the motorcycles in Australia as the convenience, carrying capacity, and wet weather protection of the tin tops experienced a wholesale shift to the four-wheelers from the 1950s onwards. But it’s interesting to note that on many separate occasions, the country was a hair’s breadth away from having its very own Triumph or Harley-Davidson. But we can still dream, can’t we?