Riders could eventually have a guide to the most crash-resistant motorcycle gear suitable for harsh summer riding conditions.

Researchers will be looking for Canberra volunteers to be part of a study into the most effective summer motorcycle gear next year (2015).

Neuroscience Research Australia (NRA) senior research officer Dr Liz de Rome, a rider since 1969, says she has been conducting laboratory research with a thermal sweating mannequin and riders, but will conduct real-world research early next year in Canberra.

Liz hopes the end result of the research will be a five-star rating for motorcycle gear that has crash protection even in hot conditions.

Liz says she is an ATGATT (all the gear all the time) rider, wearing a fabric suit and flip-up helmet on her SYM 125 scooter.

“The main problem in summer is that riders don’t wear all the gear,” she says. “Heat is the biggest disincentive to wearing the right gear. Some riders are ATGATT and if it gets too hot they just don’t ride, but a lot of riders who own the right gear opt not to wear it when it gets hot. They are leaving themselves exposed to crash injury.”

The joint study is being conducted with Associate Professor Nigel Taylor, one of the world’s leading thermal physiologists, at the University of Wollongong’s Centre for Human and Applied Physiology. They are examining how much body heat motorcyclists produce and whether riders risk reaching a physiologically damaging level of heat strain when wearing motorcycle clothing.

Liz says they started by selecting 10 of the most widely-used rider suits in Australia featuring a combination of leathers, fabrics, kevlar and protective jeans.

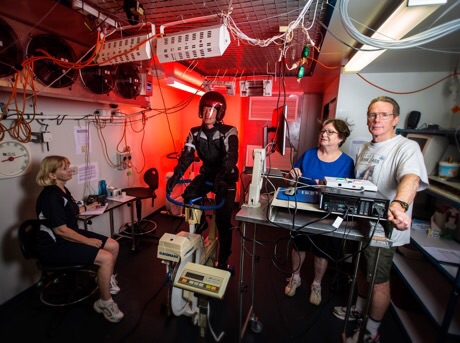

The first tests were conducted with Associate Professor Olga Troynikov from RMIT and involved thermal sweating mannequins, which look like shop store dummies, but are computerised to replicate the body warmth and sweat of a human being.

“We were able able to measure the heat insulation and breath-ability of each garment,” Liz says. “You want to wear clothing that will allow the heat of your body to escape. If the heat of your body can’t escape, you sweat and when you sweat – for your body to cool – the sweat has to evaporate.”

Liz says they had a “wide variation” in results. “Some suits are good at one thing and not at the other,” she says. “We will also test all the gear for abrasion resistance to identify the features of suits that offer both crash and heat protection.

The researchers are using a thermal chamber to test 12 volunteer “human subjects” wearing motorcycle gear.

The tests are based on a previous study with Honda Australia to measure the workload involved in on-road riding. In that study six experienced riding instructors wore masks measuring their oxygen consumption while they rode a 5km urban route with stops and a 5km rural route without stopping.

“How much oxygen you consume indicates how hard you are working and relates to your body heat production,” she says. “The amount of oxygen you consume while riding on-road is surprisingly low. It equates to slow pedalling a bicycle, compared to motocross riders whose workload is quite high.”

The climate chamber’s controlled environment is set to create the heat and humidity of riding in full sun, the researchers use a fan to replicate wind speed when riding. In each trial, the test riders pedal an exercise bike slowly for an hour and a half with three breaks for five minutes during which the fan is turned off. Trial conditions are based on average temperatures from six locations around Australia to get a range of summer conditions.

The volunteers complete four trials in a variety of gear from boots, gloves and a long-sleeve t-shirt to full protective motorcycle gear. Heart rate, skin temperature and sweat production are measured in addition to volunteers subjecting ratings of comfort.

Liz says they will then move on to real-world trials early next year in Canberra.