All brands have certain challenges to overcome, especially the historical ones. Be it a poor marketing decision, failed product launches, or embarrassing social media boo-boos, it’s almost expected that at some point all brands will make a misstep. Think Ford’s Edsel, ‘New’ Coke from the 80s, or even U2 and Apple downloading music onto people’s iPhones without permission.

But I bet I can top all those. Hell, the one I’ll share with you now makes all those look about as bad as using the wrong spoon for soup at a formal dinner. See, in the 1930s in Germany, a whole bunch of big companies got into bed with none other than Adolf Hitler himself. How’s that for giving your brand a bad name?

Along with Hugo Boss, Siemens, Kodak, Fanta, and Beyer, BMW signed on the dotted line and quite literally hitched their wagons to the Nazi gravy train.

A Young Boxer: The BMW R32

But the story really starts a full decade earlier when BMW launched their first bike, also known as the R32. Released in 1923, it’s engineering accomplishments were more than a little ahead of their time.

They opted for a boxer-engined design to ensure cooling was adequately managed in all conditions, and a solid drive shaft as a more reliable method of getting the power to the rear wheel than a chain or a belt. How much of this design was informed by motorcycle lessons learned during WWI we may never know—but so far, so good.

Of course, there’s more than one way to skin a cat, and with the moto technology of the time being so fresh, there were no real right or wrong answers to the transport challenges at hand. It’s also interesting to note that Zündapp, BMW’s main moto rival inside Germany, went with a single upright cylinder and a belt drive for their first motorcycle at around the same time.

So back we go to the 1930s, and with the storm clouds of war once again gathering over Europe, military spending—especially that of Germany’s newly elected Nazi Party after 1933—saw companies compete for one of the few remaining reliable sources of sales.

I won’t go into the morals of accepting money from such a despicable source in this story, but the history books are clear here. Despite some very obvious warning signs, Germany’s dire economic situation and sheer will to survive saw many of their best and brightest companies work hand in hand with the pure evil that was the National Socialist German Workers’ Party.

Next Steps: BMW In the 1930s

So you’re a Nazi general getting busy by planning to take over Europe. Yes, you’ll need an armada of vehicles to achieve your aims. Some big and some small. And one of the smallest would have to be das motorrad.

Light, cheap to make and able to go over, around and through obstacles that cars and trucks couldn’t, it was clearly an important tool in the Deutsche Wehrmacht’s arsenal. But the key for any successful motorcycle was one of reliability.

If the things overheated while the Afrikakorps rampaged across the North African desert or froze during cold Russian winters, then they would be useless. Similarly, if the conditions mean the bikes were becoming kaput thanks to busted chains or belts, then they’d also be no good.

So looking at the motorcycle designs available to them, what do you think the Nazi engineers found?

“What about this here BMW motorcycle? Why, look! It has a boxer engine design that will stay cool in the desert and won’t freeze over like those new-fangled water-cooled bikes.

Also, it has a shaft drive. Sure, it may weigh a bit more than a chain set-up, but it’ll handle the sand, snow, mud and branches much better than those delicate chains or belts.

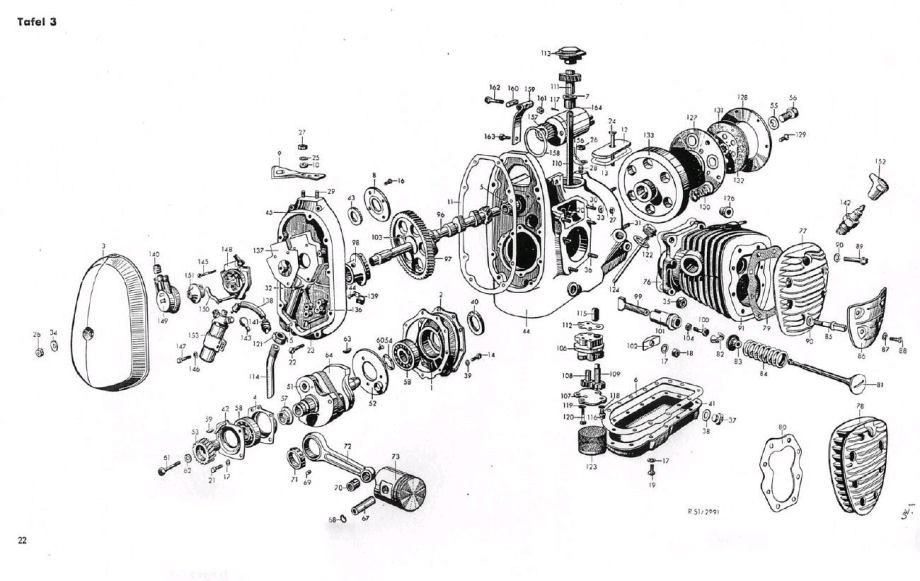

What’s that? Telescopic forks! And just to really gild the lily, it’s design means that pistons and valves are much more accessible by army engineers in the heat of battle. Sold!”

How the BMW Became the Nazi Superbike

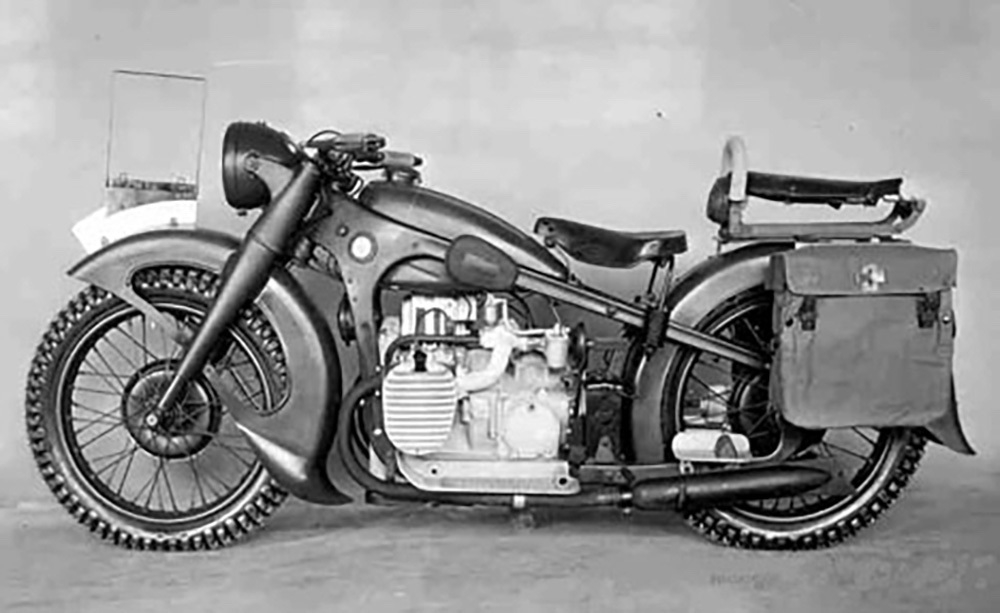

The end result? The BMW R75. Designed in 1938, the bike not only took all the continent-conquering traits of the original BMW design, but went one step further to add a sidecar.

This enabled the three-wheeled design to use that extra wheel for power, making the final design a kind of two-wheel drive vehicle including the ability to lock the differential and switch between on-road and off-road gear ratios. Oh, and did I mention the reverse gear?

BMW’s Lasting Legacy

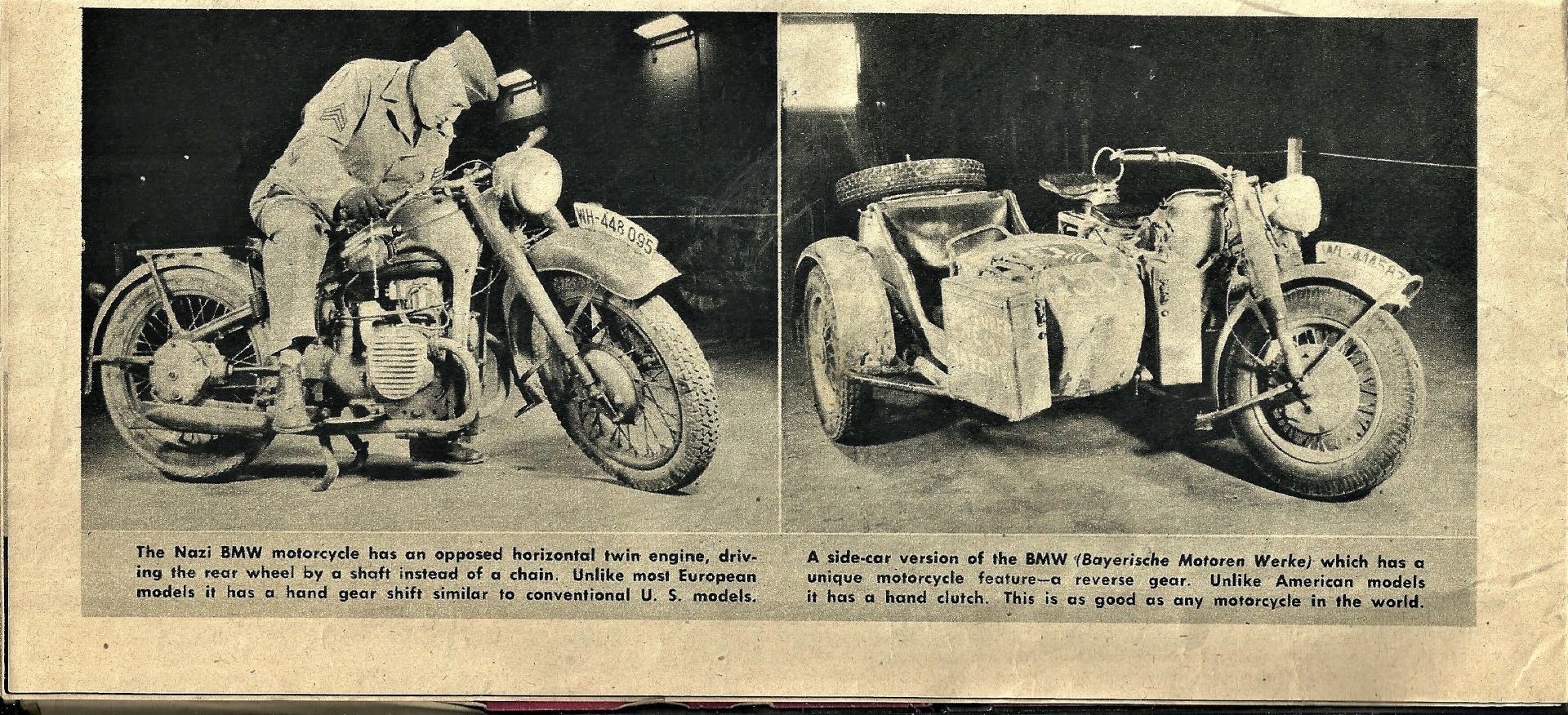

The results not only speak for themselves in the fact that BMW still use the foundations of their WWII designs to this day, but also by the words spoken and the actions taken by their enemies on the battlefield.

It’s a well-known fact that Russia’s IMZ-Ural is a straight copy of the R71. Even more compelling was the result of the American army’s analysis on captured BMW bikes during the war.

Frustrated by the metric bolts, yet stunned by just how more advanced these bikes were when compared side-by-side to their relatively primitive Harley WLAs, the soldiers tasked with studying and deconstructing the bikes didn’t mince their words. ‘This is as good as any motorcycle in the world,” they concluded.