Royal Enfield motorcycles are known for tackling all sorts of terrain at a slow and methodical pace, but now they have a limited-edition Bullet 500 Trial model with slightly more off-road ability.

It will be available in Australia for $9190 ride away which is substantially more than the $7690 for the standard Bullet 500.

The thumpers come with a single pipe that rises at a 45-degree angle, a headlight grille, slightly knobby rubber, solo seat, rear rack, bash plate and a side plate.

They come with chrome tanks with day-glo red and olive green frames.

Royal Enfield sent us this history of trials riding and Royal Enfield involvement in the sport.

Trials history

Go back to the very dawn of motorised transport at the turn of the 20th century and you will find the origin of trials, or ‘reliability trials’, as they were known.

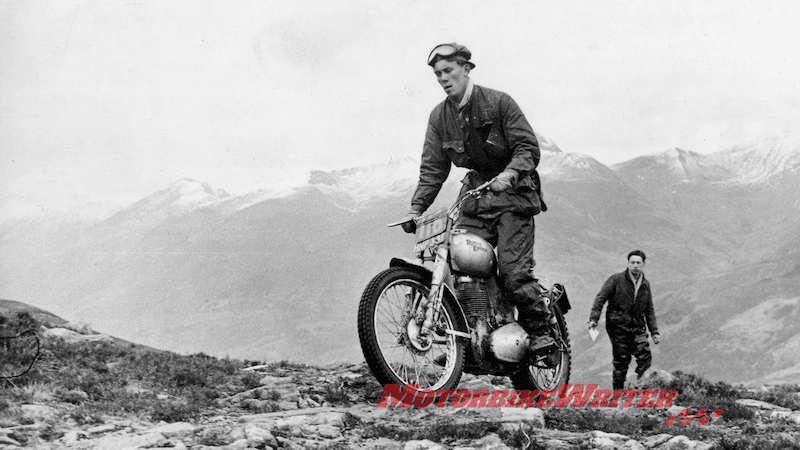

Manufacturers used these trials to demonstrate their machines’ dependability and endurance on the rough, un-metaled highways and byways of Britain. However, when road surfaces improved in the 1920s, trials competitions went ‘off-road’ to dedicated courses, where challenging terrain provided a gruelling test for both man and machine. A trials rider had to negotiate rocky hillside tracks, traverse slippery gullies, pick out a safe line along windswept ridges, slog through claggy mud and wade across boulder-strewn rivers. Points were lost if, in strictly observed sections, a rider so much as put his foot down, a fault referred to as a ‘dab’, if he careered off course or, as often happened, he simply fell off.

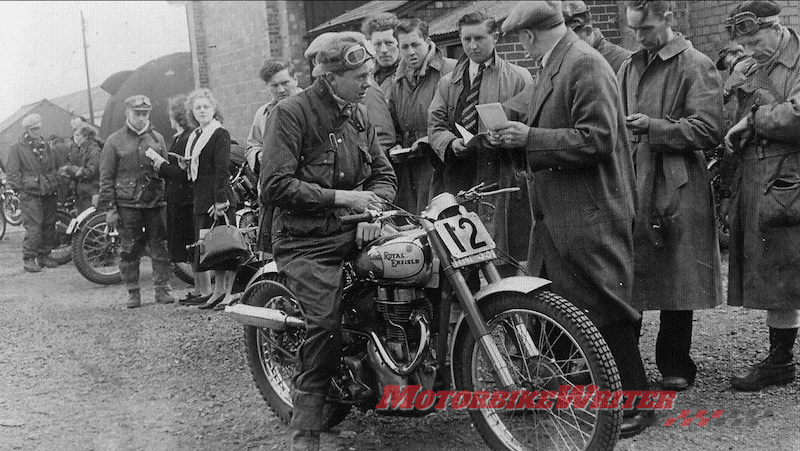

The sport became a widely recognised way of highlighting the merits of one manufacturer’s machine over that of another, with tractability, manoeuvrability and, of course, reliability, paramount. Although tuned, lightened and modified where possible to give an edge, the competing motorcycles were clearly derived from standard road bikes. In the majority of cases, competitors would ride their machines some considerable distance to an event, remove the headlight and any other extraneous parts, such as pillion seat and foot rests, give their all in the trial then hopefully still be able to ride home afterwards. Riders and bikes had to be built tough!

Spectators loved the sport. At the height of its popularity in the 1950s and ‘60s tens of thousands of them would brave the worst of the British weather to attend both the club and trade-sponsored trials which took place across the length and breadth of the British countryside every weekend. The top riders were household names pursued by fans seeking their autographs and trials wins, especially in one of the more prestigious national or international events, incontrovertibly led to sales of the road- going motorcycles from which the trials mounts originated.

Bullet Trial

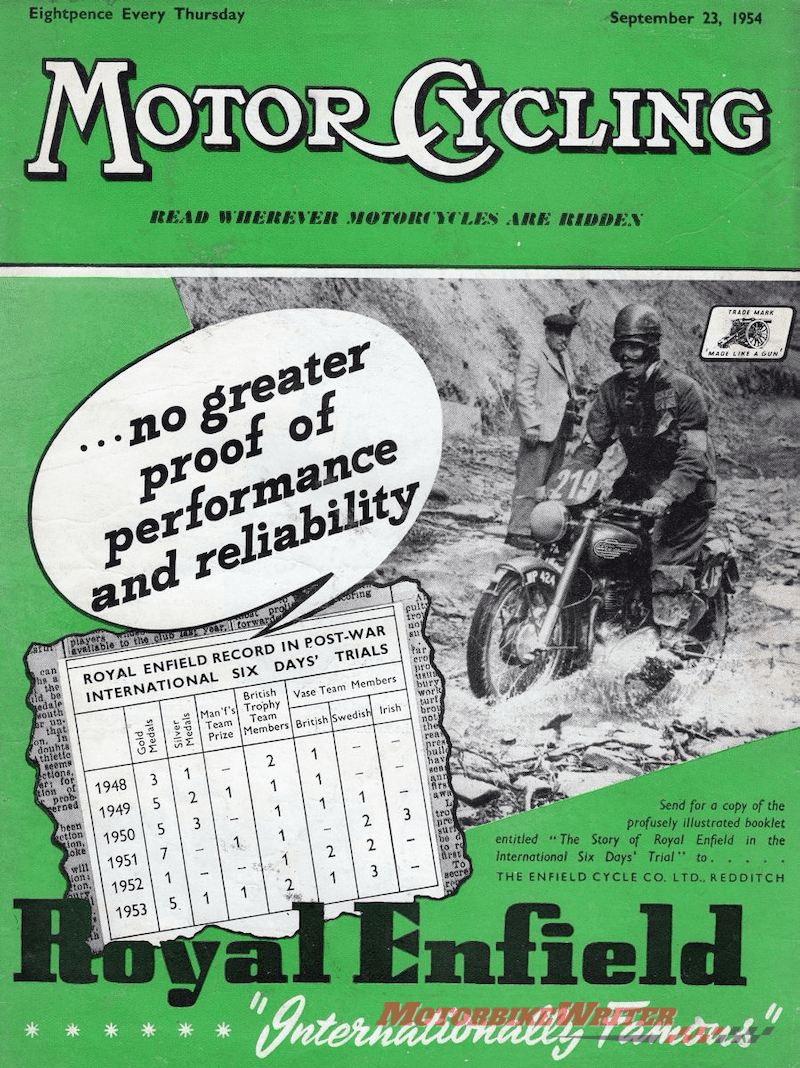

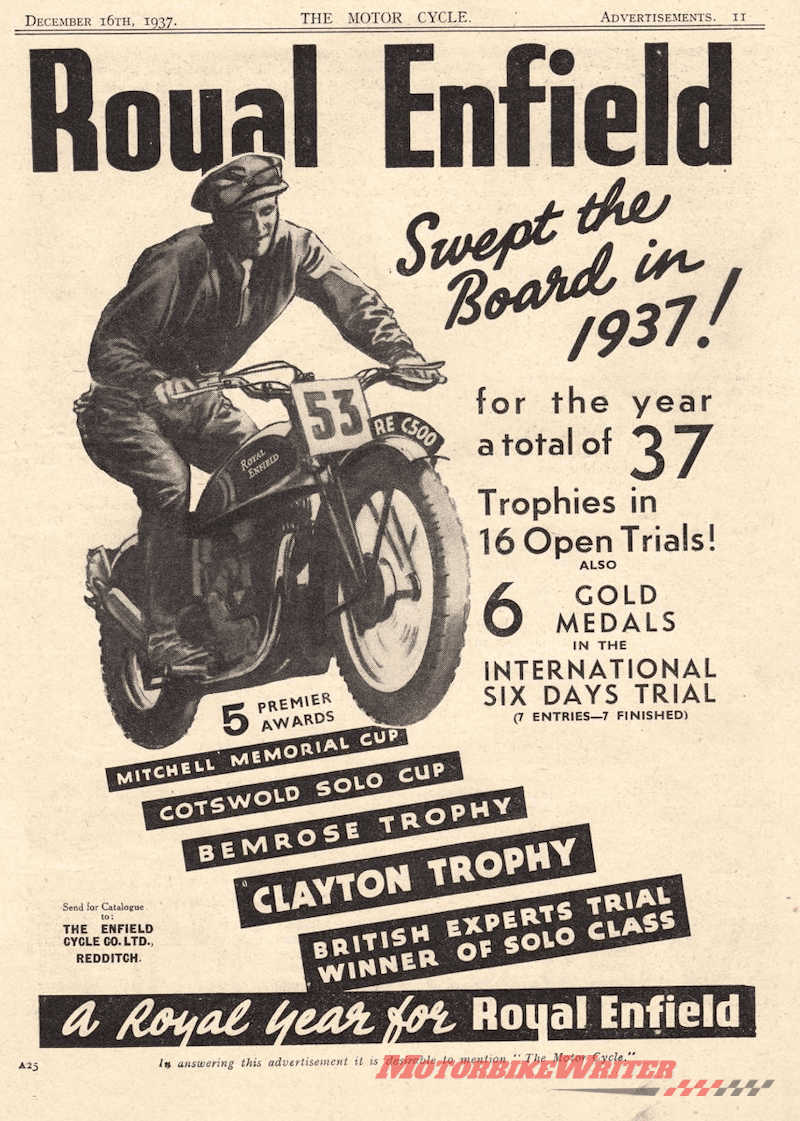

When the Bullet was launched in 1932, the company quickly heralded it as “perfect for touring or trials” and it was soon available with optional wide ratio trials gearing. As the decade progressed, its successes racked up. In the 1935 International Six Days Trial (ISDT), the indisputable pinnacle of the sport which was commonly referred to as the ‘Olympics of motorcycling’, the Royal Enfield team was the only squad riding British motorcycles not to drop a single point. In 1937, Enfield riders won a record-breaking 37 trials trophies along with six gold medals in the ISDT, with legends such as Charlie Rogers, George Holdsworth and Jack Booker riding 250 and 350cc Bullets and the 500cc Special Competition Model to victory.

But it was in the post-war era that Royal Enfield truly came to the fore in trials, largely thanks to the all-new 350cc Bullet. Even though telescopic front forks had become de rigueur from 1945 onwards, motorcycle designers had firmly stuck to the pre-war format of a rigid rear. The Bullet broke with this tradition when Enfield’s head designer, Ted Pardoe, and Tony Wilson-Jones, its chief engineer, incorporated revolutionary swinging arm suspension with oil damped shock absorbers for the first time on any production motorcycle. The suspension’s travel was rather limited at just 2” but it was enough to give its rider improved comfort and, as far as off road grip was concerned, increased adhesion.

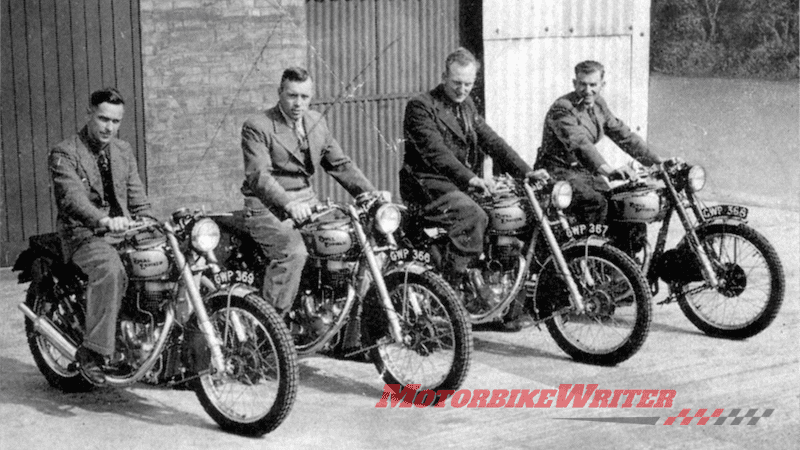

British motorcycle manufacturers usually unveiled their forthcoming year’s models at the all-important Earls Court Motorcycle Show, held in London each November. When he came to showcasing the new swinging-arm Bullet, Royal Enfield took the unorthodox step of revealing it at a trial, entering three prototype machines in the 1948 Colmore Cup.

This unexpected move was a shrewd one because the bike’s rear suspension caught everyone’s attention, including journalists from both of the UK’s weekly motorcycle magazines, The MotorCycle and Motorcycling. Both magazines published 2-page features on the bike. While victory may not have come on the course that day, it was certainly achieved in terms of publicity.

The positive showing that these new Bullets made in competitions during the following months meant that two were selected for the British Trophy team to take part in that year’s ISDT, held in San Remo, Italy. Success followed with both Bullet riders, Charlie Rogers and Vic Brittain, winning gold medals and contributing to the British team’s first place position.

The road-going version of the Bullet took centre stage on the Royal Enfield stand at that year’s Earls Court Show, and it became the backbone of the range for the following 14 years. The company’s annual sales brochures usually featured a trials variant, available to the club level rider by special order. However, pukka works machines were reserved for a select few professional riders. These were specially tuned and modified in the factory competition shop and lavished with, what were for the time, exotic lightweight materials, such as magnesium for crankcases and aluminium alloy for wheel hubs.

Johnny Brittain

Although Royal Enfield had employed a number of highly skilled riders over the years it had never had a true star. All that changed in 1950 when a precociously talented 18-year-old joined the company. John Victor Brittain, universally known as Johnny Brittain, was the son of 1920s and ‘30s legend, Vic Brittain, a multi-skilled rider who successfully competed in everything from ISDTs to TT races, scrambles and fairground daredevil stunts and who had been persuaded to come out of retirement and join Enfield for one year in order to ride a Bullet in the famed 1948 ISDT win.

Somewhat gangly, quietly-spoken and immensely dedicated, Johnny soon showed his mettle, picking up first class awards in one day trials and a gold medal in that year’s ISDT. “In the early days,” he recalls, “my competitors openly ridiculed me, deriding the spring-frame Bullet. They were still on rigid-framed bikes and would say things like: ‘I pity you having to ride that Enfield with that bouncy rear suspension.’ They were soon laughing on the other side of their faces when I began winning, and it took several years for all the other manufacturers to catch up and adopt the Bullet’s swinging arm suspension, which gave me a real edge.”

On his famous 350cc trials Bullet, registration number HNP 331, Johnny won the prestigious Scottish Six Days Trial twice, an arduous 900 mile contest spread over six long days, (1952 and 1957), the formidable Scott Trial twice (1955 and 1956), the tough British Experts Trial twice, where he was its youngest ever winner (1952 and 1953), and amassed over 50 major championship wins and a huge haul of open trial first places. Beginning with his first ISDT campaign on a Royal Enfield in the 1950 competition, Johnny accumulated 13 gold medals over 15 years, although some of those rides were on a 500 Twin and a 500 Bullet rather than HNP 331.

Johnny Brittain’s works trials Bullets of 1956 and 1957 were all conquering. In ’56, he triumphed in the ACU Star championship and his tally of wins included the Welsh Trophy, the Scott, Mitchell and Streatham trials, the Alan Hurst, Shropshire and Patland Cups as well as second places in the Scottish Six Days Trial and two other major events. The following year, he clocked up wins in the Scottish Six Days, Vic Brittain (named in honour of his father), Cleveland, Travers, Red Rose and Cotswold Trials amongst others.

To mark this tremendous run of results the firm released a Bullet closely based on his winning machine in 1958. Named the 350 Trials Works Replica, it aimed to give its rider a great starting point from which to compete in trials. Employing the same lighter, all-welded frame made of aircraft quality chrome-molybdenum, it sported a slimmed-down 21⁄2 gallon petrol tank, 21” front wheel, knobbly tyres, alloy mudguards, a sump guard, high-level exhaust, Lucas Wader magneto and a slimline gearbox with low gearing.

Even the engine was given the works treatment as its bottom end was formed around heavier 500cc Bullet flywheels, resulting in a motor which plonked like a gas engine, and its barrel was cast in aluminium alloy. Finished in polychromatic silver grey, the Trials Works Replica was a beauty to look at as well as to ride.

Johnny wasn’t Royal Enfield’s sole trials rider though. There was always a works team at major events which, over the years, included Johnny’s younger brother, Pat, as well as other leading lights of the trials circuit such as Tom Ellis, ‘Jolly’ Jack Stocker, Don Evans, Peter Fletcher, Peter Gaunt and Peter Stirland. Even Bill Lomas, long before he became a two- time motorcycle grand prix world champion, won a first class award on a Royal Enfield trials Bullet.

By the end of the 1950s, however, the days of the heavyweight trials motorcycle were numbered. Responding to the trend for ever lighter bikes, with revvier engines that could snap the front wheel up and over obstacles and make best use of the constantly improving tyre compounds and tread patterns, Royal Enfield refocused its trials ambitions around the new, unit-construction 250cc Crusader.

The story of Royal Enfield’s trials motorcycles doesn’t end with the 1967 Redditch factory closure. Over subsequent decades, many owners have undertaken trials conversions, using both British and Indian road Bullets as their starting point. Although the majority have standard gearing and see only occasional light greenlaning use, a significant number have been built to fully competitive specification and are regular entrants in classic trials events, including the celebrated Scottish Pre-65 Trial, a revered annual competition held in the highlands of Scotland ahead of the Scottish Six Days Trial.