While you could argue that all bikers have a little bit of crazy in them, anybody with a decent amount of riding experience under their black leather belts will tell you that there’s dangerous bikes and then there’s dangerous bikes. The first kind are any bikes with decent power. The kind of power that can get you into trouble – either with the law or yourself – if you lack the judgment to be able to control your right hand where necessary.

But this isn’t the bike’s fault. That brand new 1000cc Suzuki GSX-R isn’t the one that sent you sliding on yr butt cakes across the freeway and into oncoming traffic. That was all your own doing. But what about when your self-control and riding skills are up to the task, but the bike isn’t?

It’s a problem you’ll rarely encounter in the modern world, but for a while there it was a little more common. So which bikes are we talking about? Come with me now and get that ambulance service on speed dial as we look at the top five most dangerous motorcycles ever made.

5. The Brough Superior SS100

Now I know I’m treading on sacred ground here, but allow me to explain. Yes, the Brough Superior is legendary and it will always hold a special place in my heart as the great Granddaddy of all modern bikes. But (and this is a big but) you have to remember that what we had here was essentially 1920s technology putting out 50 hp or more in various configurations over the next decade.

Other bikes of the day were lucky to have 15 horses, so the modern day equivalent would be like Ducati or Honda releasing a sportsbike with 350 hp and zero electronic aids to contain it. Yowsers.

And with WWII and all its technological advancements yet to happen, George Brough had created a real mechanical freak that few could ride properly and still fewer would be able to master. Even with truckloads of riding experience and numerous Brough Superiors to his name, the bike was too much for T.E. Lawrence (aka Lawrence of Arabia).

A survivor of World War One, a Brough took his life in 1935 after he misjudged an overtake, hit a dip in the road and went over the bars without a helmet on. Makes you wonder how many other non-famous Brough riders met a similar fate, yes?

4. The 1971 Suzuki TM400

Ahhh, the Seventies! When men were men and hospitals were full of motocrossers. Thanks in large part to the hit film On Any Sunday, off-road motorcycling had suddenly become a big sport at this time and all the manufacturers were scrambling (pun fully intended) to get their dirt products into showrooms and selling. And as we all know, nothing succeeds like excess. So in that spirit, Suzuki Motorcycles pulled the satin covers of their first proper, open-class motocrosser in 1971. Powered by a very impressive 400cc two stroke smoker and putting out 40 hp, people were rightly pumped to try these little yellow beasties in the dirt.

But that’s precisely when the bike’s shortcomings became apparent. Built on a too-soft frame and with supremely under spec’d shocks front and back, the thing was a handful to ride even for a pro. And the problems didn’t stop there. Suzuki also included the hilariously-named “Pointless Electronic Ignition” system (I kid you not) that did a really piss poor job of advancing and retarding the bike’s timing. The net effect here was that the engine would randomly move its peak power around the rev counter in a life-threatening game of cat and mouse.

From all reports, it loved nothing better than to surprise you with a big kick in the backside right in the middle of a tight corner. Suzuki went into overdrive to stop all the broken bones with a heavier flywheel and better shocks. They eventually dropped the pointless ignition too, but it didn’t really matter in the end as they were already being outclassed on the world’s tracks by an army of far superior Maicos and CZs. Ooops.

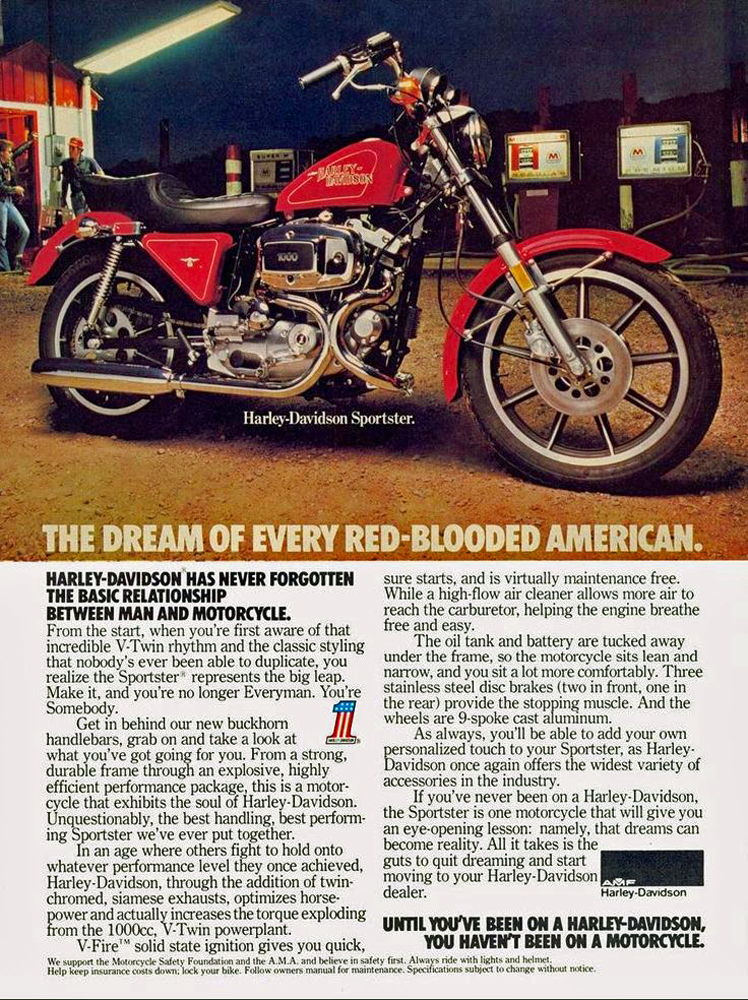

3. Late ’70s & Early ’80s Harley Sportsters

Anyone with even a cursory knowledge of Harley’s checkered past will know that the late 1970s and early 80s were dark years for the Milwaukee giant. A ham-fisted corporate buyout from the American Machine and Foundry Company in 1969 saw the legendary company crumble into a bumbling mess of a business plagued by poor quality, union issues and tanking sales.

Running on nothing but fumes and the pop culture status the 1960s had afforded the brand, they somehow managed to continue releasing new bikes, including their all-important Sportster models.

And as for those poor, unsuspecting customers who actually fronted up to a dealer with a bag full of their hard-earned to purchase a bike in the early 80s, well… let’s just say they inherited all the fruits of the previous decade’s complete shit show. Still a full 12 months away from being rescued by a bunch of brand faithfuls lead by Willie G. Davidson himself, the Sportsters of this era were as fast and manoeuvrable as they were well-built. That is to say they were some of the worst, slowest and most cumbersome bikes Harley ever produced.

They probably would’ve hurt more riders if it wasn’t for the fact that they basically shook themselves to pieces soon after they left the showroom floor. I pity the poor Harley Service Managers of the time; how exactly do you tell a customer that they’ve bought a chubby, shaking lemon of a bike without losing your job in the process?

2. The 1997 Suzuki TL1000S

In stark contrast to the Harleys, the Suzuki TL1000S is a great example of a bike that was dangerous not because it was crap, but because it was pushing the advanced engineering envelope a little too far. On paper, the thing looked like a real winner. A big v-twin sportsbike from a respected Japanese manufacturer? What’s not to like? So in 1997, Suzuki fans were frothing at the chops to get their hands on one. And the bike did not disappoint. Great reviews saw good sales, but then things went a little southward.

Suzuki’s engineers had faced a considerable challenge when placing the big, long v-twin in the bike’s frame. Put simply, the engine was taking up the space in front of the rear wheel where the bike’s shock usually sits. Their answer was to go with a tricky and largely untested shock, damper and spring set-up that had been lifted directly from ‘90s F1 racing. The rear spring was placed on the right side of the bike and a remote “rotary style” rear damper tried to do its job through a set of spinning arms, some valves and a tablespoon or two of hydraulic fluid.

But it just plain didn’t work and any serious up-and-down action for the rear shock would result in the oil overheating and the damping going right out the window. So the bike’s rear end would get lazy. Then you had a big, torquey v-twin and a soft, saggy rear wheel which made the front of the bike about as steady and reliable as a tipsy Italian Prime Minister. And into the scenery you’d go. Look hard enough and you’ll still find a bunch of TLS devotees out there. You’ll be able to spot them easily enough; they’re the ones on crutches swearing black and blue that the bike is the best thing they’ve ever owned.

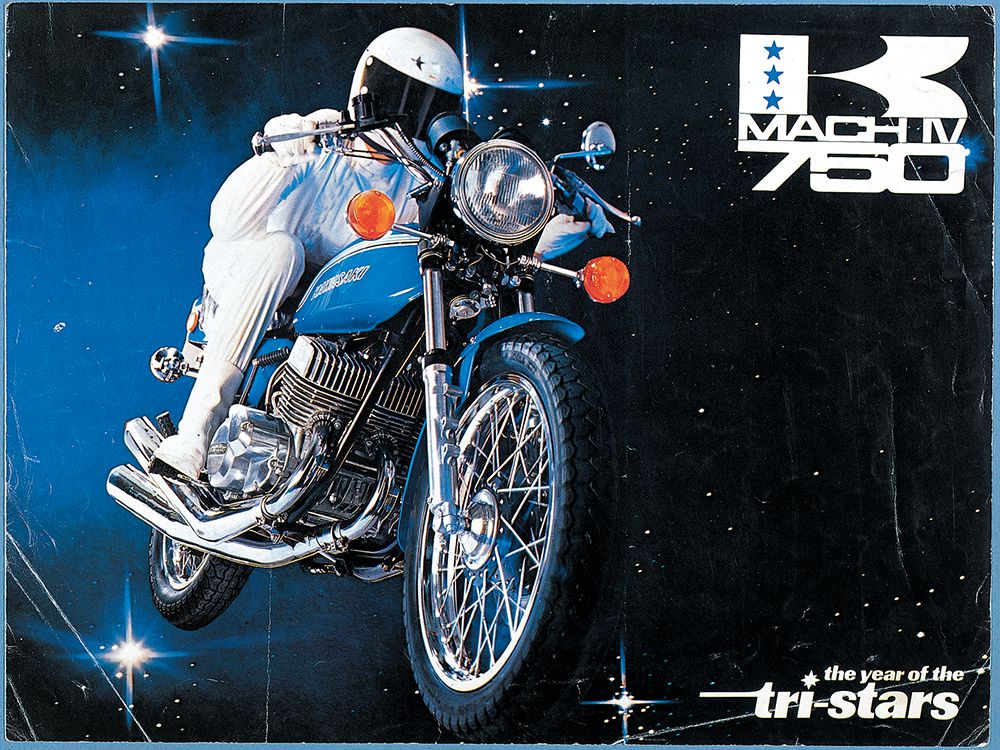

1. The 1972 Kawasaki H2 Mach IV

And so we come to the top spot. And what a bike it is. Following on from the almost-equally-as-dangerous H1 Mach III 500cc, the ‘72 two-stroke triple with an astounding 750 cc’s showed that Kawasaki has learned nothing from the broken bones caused by the H1. With a jaw-dropping combination of far too much power, a rear-biased weight balance and a frame seemingly made from rubber tubing, the H2 was an accident waiting to happen.

And did I mention the pencil-thin front forks, the totally under-specced brakes and the horrible 1970s rubber? I may have also neglected to talk about the fact that the bike would spontaneously wheelie under full-throttle acceleration when the two-stroke triple hit the 3,500 rpm power band on its way to a 12-second flat quarter-mile. And that’s on a bike that weighed in at 190 kilos dripping wet. Hot damn, what a wild ride that must have been. It’s like they didn’t even bother to test the thing before they started selling it.

Needless to say, even a pro rider would have been fighting to keep the little buggers under control, so us mere mortals had little to no chance of managing them. Lucky for Kawasaki it was the free-wheeling ‘70s, so despite the army of injured riders and smashed-up H2s, they just grimaced a little, pointed at something off in the distance and then pretended it all didn’t happen.

Or more correctly, they beat their engineers and test riders with a bamboo stick, and got them to make some rather hastily-conceived ‘safety’ mods for the ‘73 and ‘74 models. After all, market research has since shown that customers find it very hard to purchase new motorcycles when they are dead. Who’d have thought?