So, just how much do you know about T.E. Lawrence? Who, you ask? And as you do, the long dead legends of motorcycling like Burt Munro, Evel Knieval, and Steve McQueen all roll in their graves. See, without Tomas Edward Lawrence there’d likely be none of them to follow in his footsteps. And that’s because he was the first truly modern motorcyclist.

Yes, I’m being tricky, because if I had used his other name—Lawrence of Arabia—you’d have no doubt realized who I was referring to in a heartbeat. After all, how many motorcyclists do you know with a blockbuster Hollywood film about their lives that won seven Oscars? Shame there were barely any motorcycles in it.

Lawrence of Arabia: From Wales to Mesopotamia (it Rhymes!)

Born in Wales in 1888, Lawrence’s family moved to Oxford in 1896, where he attended the 400-year old Jesus College. Between 1910 and 1914, he worked as an archeologist for the British Museum, chiefly at Carchemish in Ottoman Syria.

Of course, he was in the Middle East when World War I broke out, and being the manly type that he was, he immediately signed up for service and was transferred to Egypt to serve in the British Army’s Arab Intelligence Service. Two years later, he traveled to Mesopotamia—where he became involved in an Arab revolt against the Ottoman Empire.

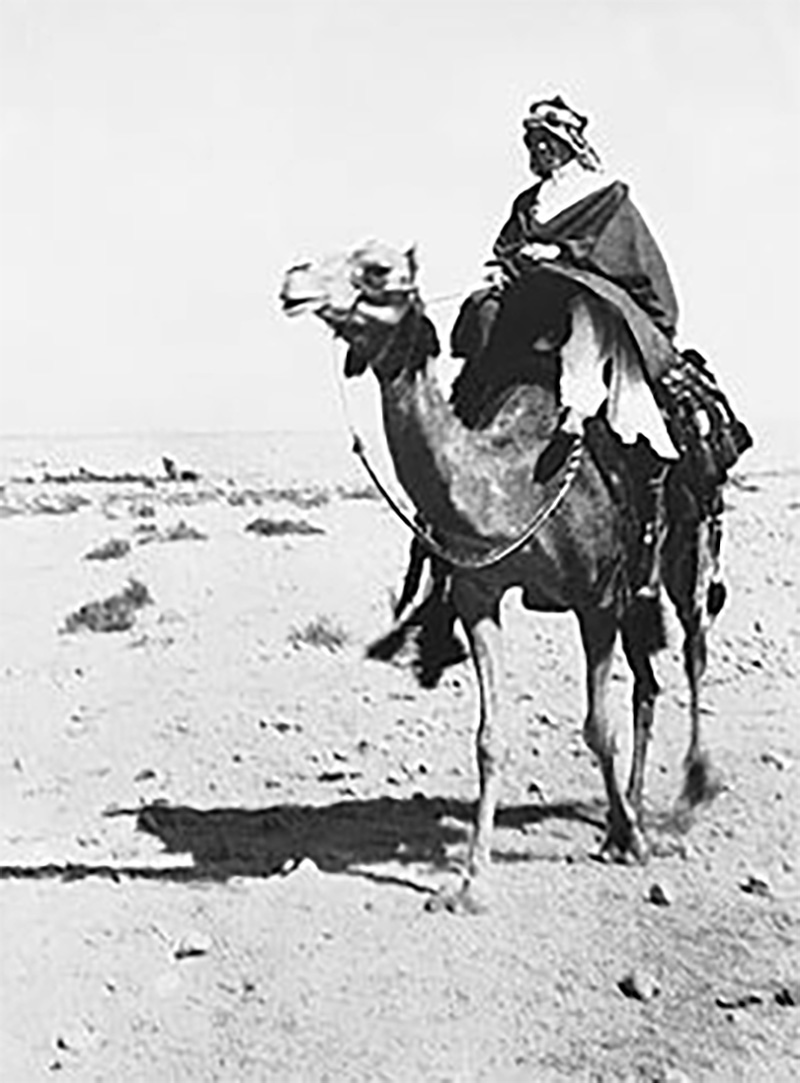

The movie of his hijinx during these times made them famous, and it’s the visual of him riding on a camel through the desert in full Arab garb that sticks in your head when the movie is raised. But who wants a single horsepower when you can have 50?

After the end of the war, Lawrence joined the British Foreign Office, where he continued to work with MIddle Eastern operatives. But all that came to an end in 1922 when he retreated from public life and decided to join the RAF. And this is where all his moto fun started.

T.E. Lawrence: Anything but Average

Despite his rank as Colonel in the army, T.E. Lawrence was an enlisted Aircraftman in the RAF where he helped develop rescue motorboats. But it was clear from even the most casual observers that this was no ordinary, lowly private.

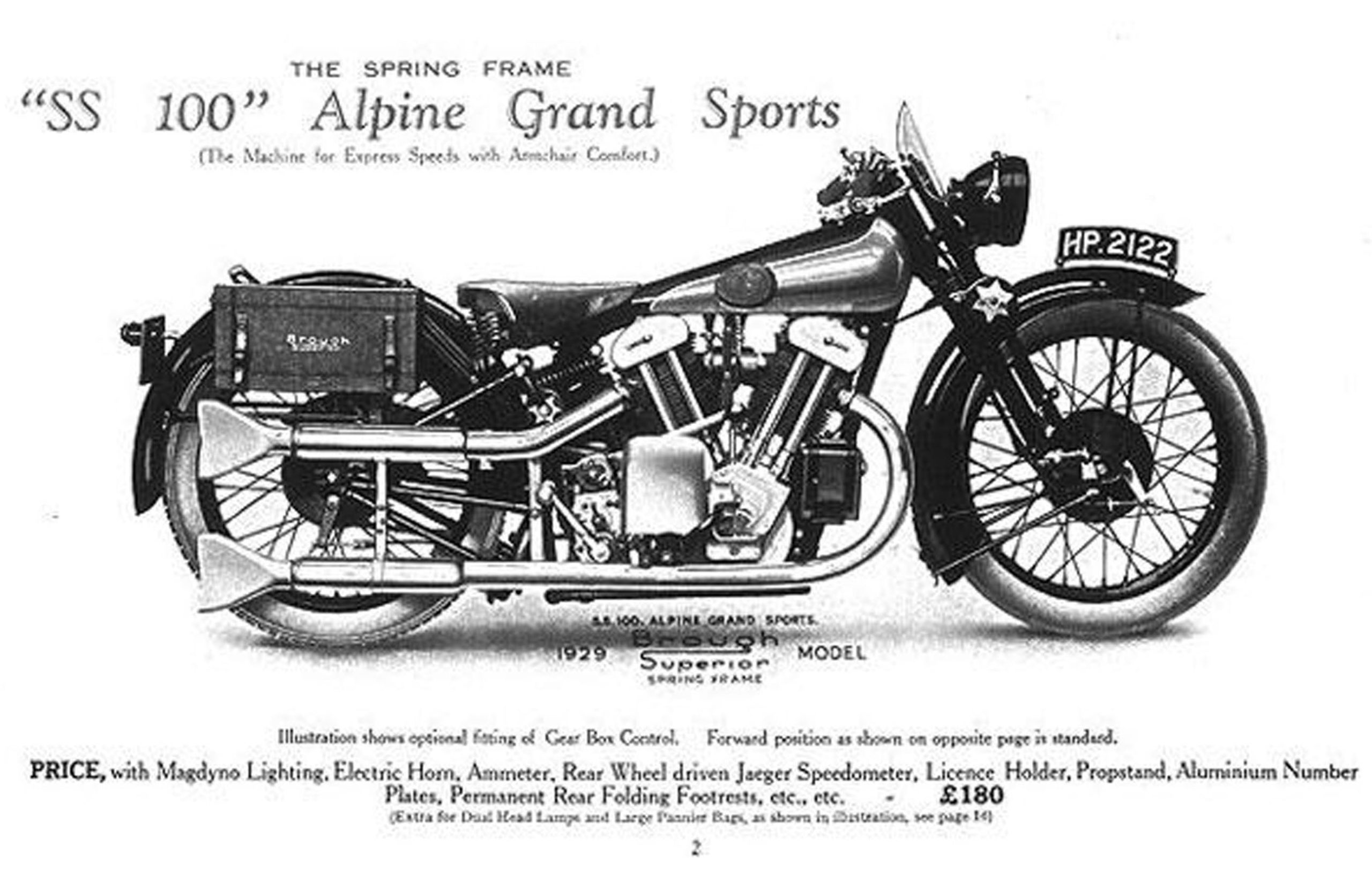

One dead give-away was his chosen form of transport; the almighty Brough Superior. Pronounced ‘Bruff’, the bikes were powered by a one liter JAP v-twin engine that was able to push the bike over the legendary 100 MPH mark.

Made by hand by George Brough in Nottingham from 1925 onwards, the bikes were essentially Rolls Royces on two wheels—and were even given permission to use that line in their advertising by the legendary auto makers.

But unlike the Rollers, Broughs weren’t known for their luxury and comfort. Instead they were known for the ability to go fast. Very bloody fast.

Straight out of the box in their 50 hp guise, you could ‘ton up’ on them—but in 1934, they released a 75 hp version called the ‘Alpine Grand Sport’ that had an extra 25 horsepower.

I need not tell you that riding a bike made in 1925 at 100 mph is in no way equivalent to riding a modern bike at the same speed. With World War II yet to happen, all the advances made in that period with lubrication, fuel injection, cooling, tyres and overall reliability were still on the horizon. To say it would’ve been an ‘exciting’ ride is like saying that amphetamines ‘pep you up’.

The Original Motorbike Writer

Lawrence owned eight of the beasts over the course of his life, which again testify that he wasn’t exactly a working man just trying to get by. Indeed, at around £200 each, he could have had a Welsh country cottage for about the same price in the 1920s. But we’re sure as hell glad that he wasn’t that sensible.

We’re also very glad that riding Brough motorcycles at top speed wasn’t the only thing he liked to do with them. Being a writer at heart, Lawrence waxed lyrical about the bikes—and in particular about one he called “Boa” or “Boanerges” which means “Son of Thunder” in Aramaic.

“Another bend: and I have the honor of one of England’ straightest and fastest roads. The burble of my exhaust unwound like a long cord behind me. Soon my speed snapped it, and I heard only the cry of the wind which my battering head split and fended aside. The cry rose with my speed to a shriek: while the air’s coldness streamed like two jets of iced water into my dissolving eyes. I screwed them to slits, and focused my sight two hundred yards ahead of me on the empty mosaic of the tar’s gravelled undulations.”

- T.E. Lawrence, from ‘The Mint’

And if that isn’t one of the very best pieces of motorcycle writing ever concocted, I’ll be damned for all eternity.

The End of the Road for T.E. Lawrence

Sadly, Lawrence would soon succumb to his love of Broughs and speed when, while riding his seventh Brough in 1935, he lost control.

From Wikipedia: “Lawrence was fatally injured in an accident on his Brough Superior SS100 motorcycle in Dorset close to his cottage Clouds Hill, near Wareham, just two months after leaving military service. A dip in the road obstructed his view of two boys on their bicycles; he swerved to avoid them, lost control, and was thrown over the handlebars. He died six days later on 19 May 1935, aged 46. The location of the crash is marked by a small memorial at the roadside.”

Prime Minister Winston Churchill attended his funeral and described him as “one of the greatest beings alive in this time”.

In an interesting posthumous tidbit, one of the doctors looking after him was neurosurgeon Hugh Cairns, who went on to study motorcycling head injuries of both military and civilian riders in great depth. His research in large part led to the widespread use of crash helmets by both military and civilian motorcyclists. So next time you put yours on, make sure you spare a thought for Lawrence of Arabia and his Broughs.