A bloke by the name of Christopher Mims is over at The Wall Street Journal getting the nitty-gritty details on why we still have a semi-conductor chip shortage, as well as why we haven’t yet caught up with demand for the bloody things (despite raging sales figures).

The results are fascinating if not a tad worrisome – and a good man by the name of Stephen Howe is stuck right in the middle of it all.

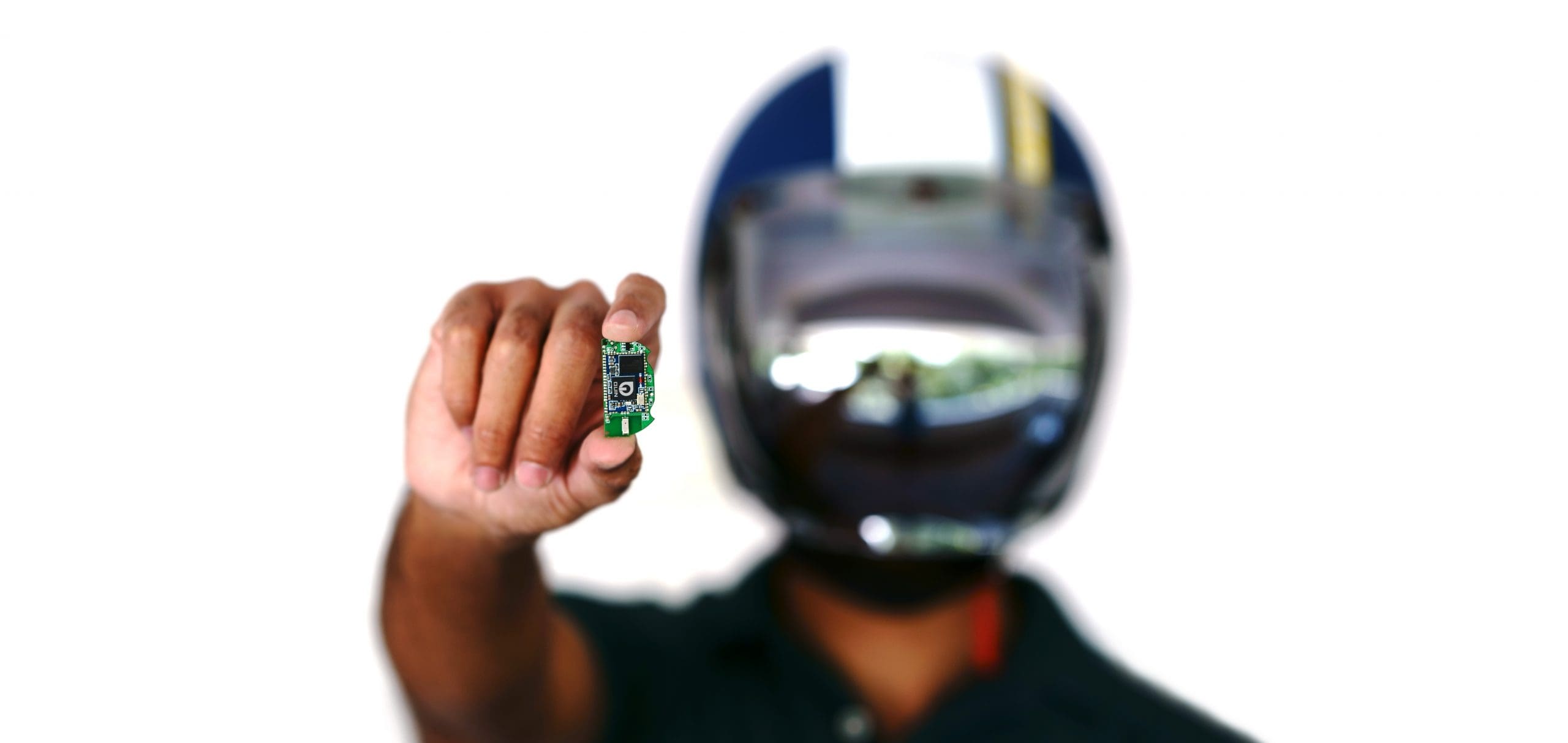

Howe sells the very machines that make microchips. From smartphones to motorcycles to the tablet-mounted kiosks running at full capacity down the road in the nearest Starbucks, Howe’s dealt with them all. Most, Mims writes, are “at least ten years old, since that’s about how long the best-capitalized chip manufacturers – like Samsung, Intel (INTC 1.31%) and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing (TSM 3.36%) – hold onto new chip-making equipment. But they can be much older.”

Howe has also noticed a trend in the microchip industry; since his company’s startup in 1998, the man has had manageable fluxes of supply, “that by turns fill and then empty his warehouses, which are located in Italy, Malaysia, and Texas.”

Since 2016, however, there’s been no filling of his warehouses.

Demand has spiked to such heights with tech made to replace basic to-do’s (like a Wi-Fi-enabled Brita “smart” pitcher that can re-order its own water filters, courtesy of Clorox Corp.) that his company – and others like his – can no longer keep up.

And that was before 2020.

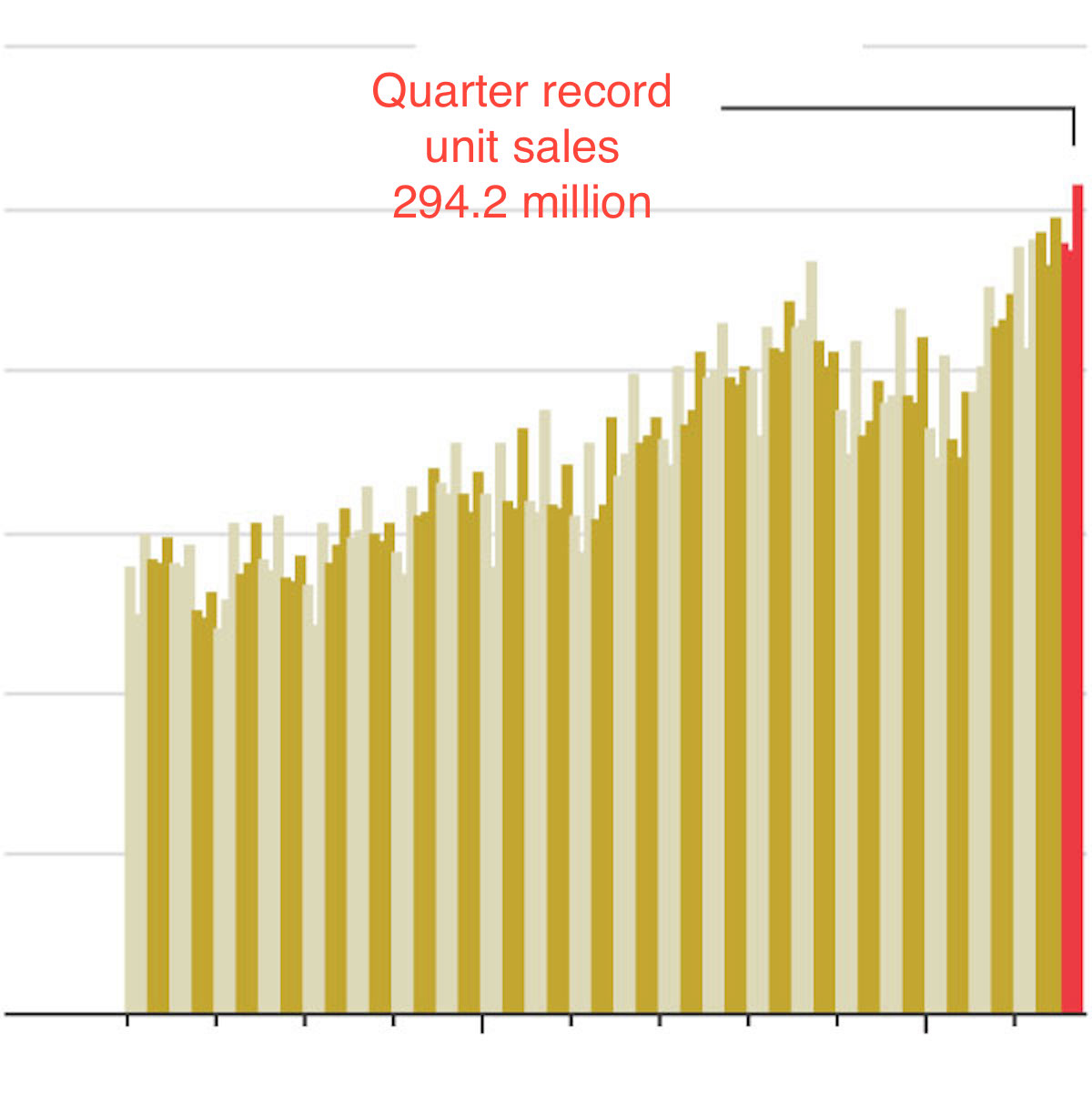

Now in 2021 (a mere year later and despite the shortages), the report tells us that “the semiconductor industry sold more chips than at any point in history.” (according to the Semiconductor Industry Association)

Well, one reason is the aforementioned advancement of technology (dubbed by many as ‘The Internet of Things’) where tech is embedded in items as mundane as a water pitcher.

More techy stuff, more chips.

The other, however, has to do with the industry cycle itself. At the time, it wasn’t created to handle such a mass demand – and it’s starting to really show.

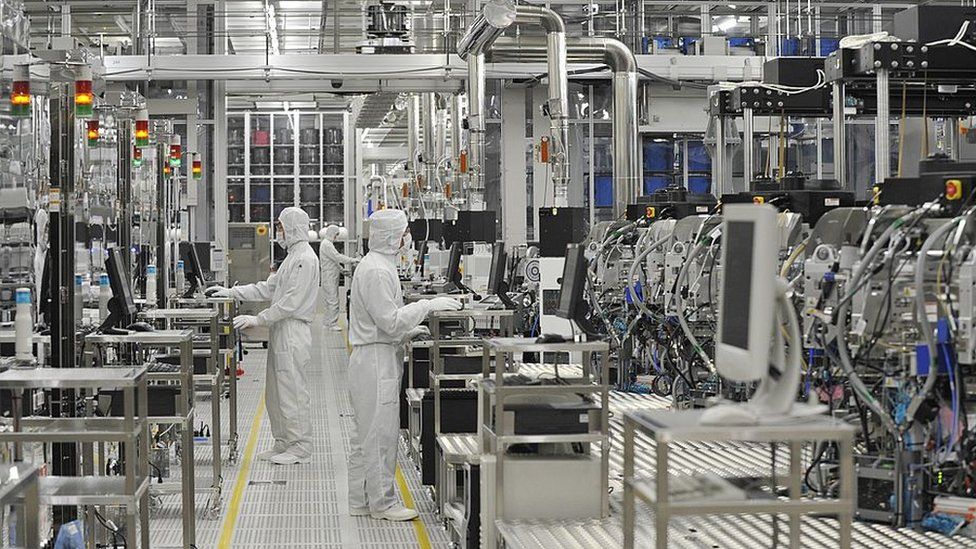

“Chip manufacturers are responding to all this demand by pledging to make more chips than ever, but ramping up manufacturing of the kinds of chips that so many companies need right now is difficult or impossible, for a number of reasons,” explains Mims.

“One is that expanding the capacity of a fab – the factory in which microchips are made – takes months even under the best of circumstances, in part because of the almost unbelievable complexity of making chips – even those using a somewhat older technology.”

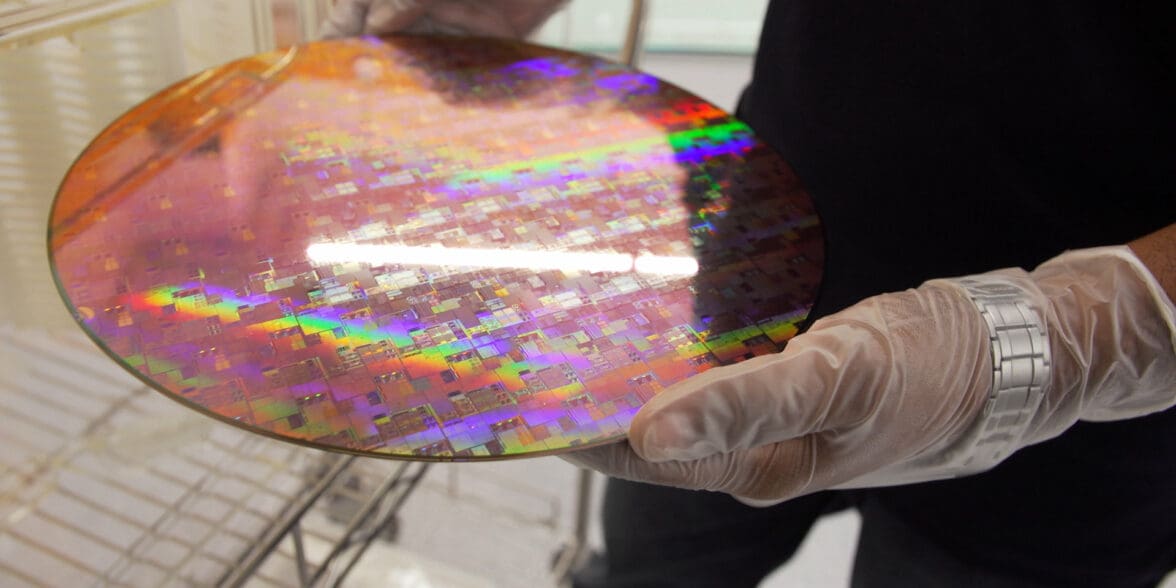

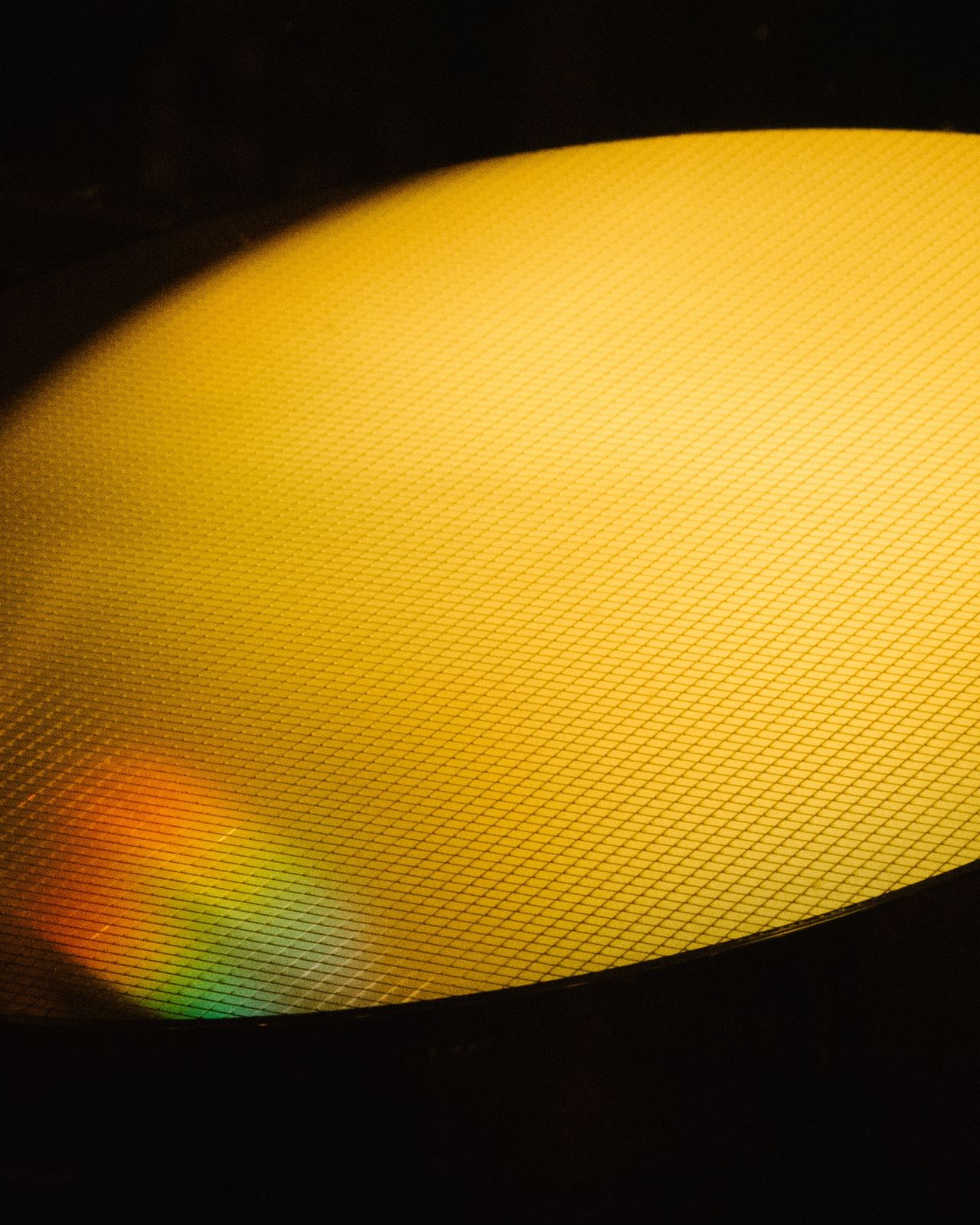

“Making a chip with cutting-edge technology, on 12-inch circles of pure, crystalline silicon known as ‘wafers,’ requires lasers so precise they can create features on microchips just five nanometers, or billionths of a meter, thick.”

To put Mims’s words into a real-life comparison, the span of five nanometers is only slightly wider than the width of a single strand of DNA.

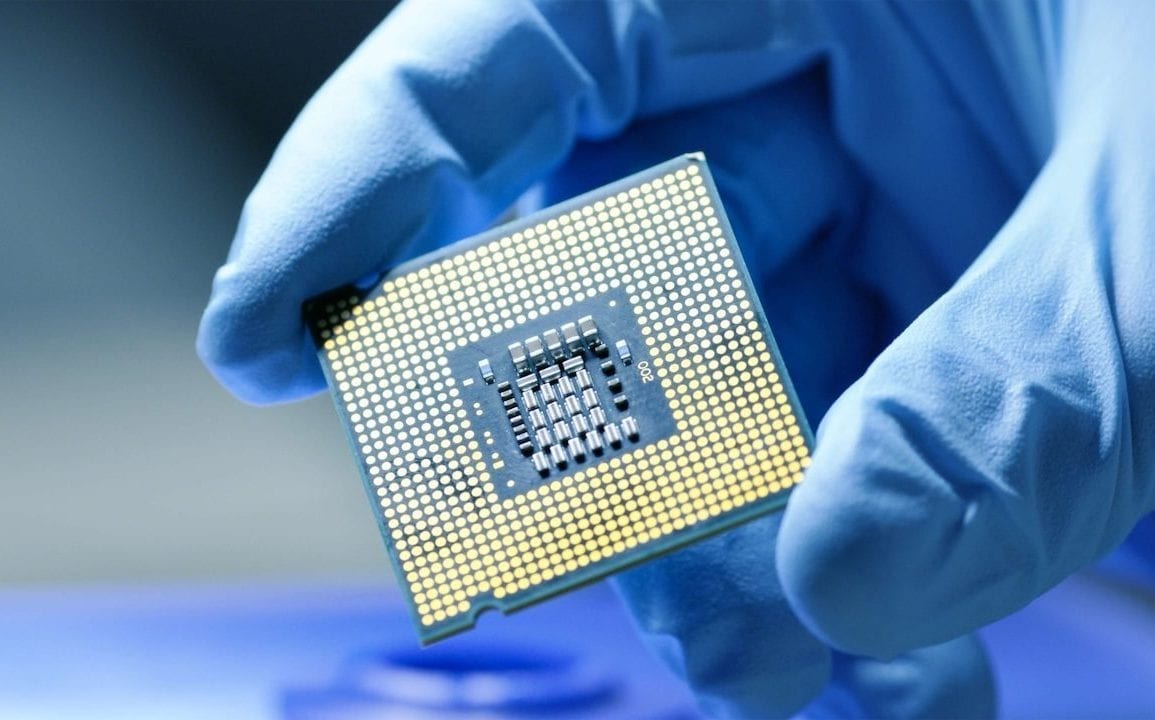

“Those chips, which include the processors that Apple and Samsung tout whenever they come out with a new phone,” continues Jamie Potter, CEO of Flexciton, “may require more than 1,000 passes through different machines inside a chip-making factory.”

“Making chips based on older technology involves 8-inch wafers and circuitry many multiples thicker, but still requires up to 300 passes through one sort of machine or another.”

In short, a new laptop processor chip costs a lot on labor, bumping up the price to hundreds of dollars – a far cry from the older-generation chips that cost just a few dollars (some as little as pennies), given they’ve been around for so long.

Yet we still need both kinds of chips to supply our industry.

Potter is in charge of a startup that makes software to help chipmakers optimize their manufacturing plans – a niche market that is trying to adjust the cycle of the industry into providing for the demand without cinching chip production rates.

“Even if a startup or less-experienced chip manufacturer can obtain chip-making equipment (China has been subsidizing domestic chip manufacturers of this sort for over a decade), it may not be able to make chips well enough to make a profit. Even the best chip manufacturers throw out on average 10% of the chips they make, and getting the percentage that low requires considerable technical expertise,” continues Mims.

What doesn’t help is that the chip shortage has also caused prices to spin out of control. The article states that “a Canon FPA3000i4 (a piece of lithography equipment manufactured in 1995 used to etch circuits in chips) was worth as little as $100,000 in October 2014. Today, it goes for $1.7 million.”

In short, if anybody wants to make older chips to save money (since they’re still used today), they’re either going to have to pay out the nose for the older stuff to start production or hop on a ‘waitlist’ for new equipment.

Currently, today’s waitlist for newer chip manufacturing machines is longer than 6 months out – and the lineup shows no signs of stopping.

Be sure to leave a comment, and as always – stay safe on the twisties.