If you are riding through mountainous areas, you and your bike could suffer from altitude sickness.

It’s an illness caused by high altitude with symptoms including hyperventilation, nausea, headaches, nose bleeds and exhaustion resulting from a shortage of oxygen.

Meanwhile, your bike can also suffer power losses. Carburettored bikes suffer more, while really high altitudes can even affect fuel-injected bikes with computerised engine mapping that adjusts the air/fuel mixture according to information from the oxygen sensors. However, they simply can’t manufacture extra oxygen.

To compensate, use a higher octane fuel or an octane booster and if your bike has varied engine maps, select the highest output. Turbo or supercharged bikes will function better. If you can adjust the air/fuel mixture, make it leaner (less fuel and more air).

Most people are only affected when they get to about 2400m (8000ft), which is higher than Koscuisko, so it’s not something most Aussies experience.

My first experience of altitude sickness was in the Rocky Mountains in Colorado where, even at 1200m (4000ft), I felt mildly hungover despite only having had one beer the night before.

I’ve since ridden to 14,110ft (4300m) to the summit of Pikes Peak and when I arrived at the top I could hardly get off the bike. My arms and legs felt like lead.

Within minutes my head began to ache, my eyes felt like they were popping out of their sockets and I felt slightly ill. I stupidly had coffee and a donut and felt worse.

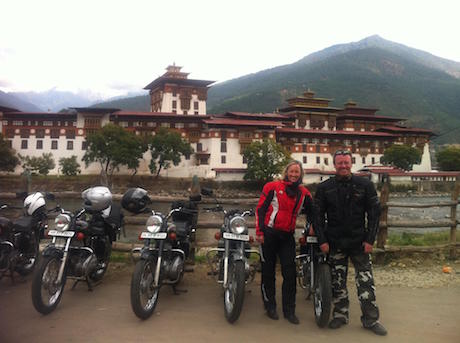

Mike and Denise Ferris of the famed Ferris Wheels Motorcycle Safaris touring company have heaps of experience in high altitudes with their tours in the Himalayas and South American Andes, so we asked their tips on beating altitude sickness.

“The most successful preventive strategies are simple and logical; spend a couple of days and nights preparing at intermediate altitudes, take it easy with no exertion, drink plenty of fluids, go easy on the alcohol. This doesn’t mean we can’t enjoy a drink or two, but it should be taken in moderation,” Mike says.

“Probably the most important rule-of-thumb is to not allow yourself to become dehydrated. Mild altitude sickness on its own can be uncomfortable; you may experience mild head throbbing, sleep disturbance, dizziness, shortness of breath, anorexia (loss of appetite), lethargy. But if you complicate this by becoming dehydrated, it can become much more debilitating; heavy fatigue, nausea/vomiting, nosebleed, cramping, blinding headache, racing pulse.

“A few bloodspots when you blow your nose is not a big concern. Your sinuses are a series of tiny capillaries containing blood and air. The reduced external air pressure at altitude results in a relative increase in the internal air pressure and these capillaries sometimes burst. No big deal unless you’re haemophiliac.

“Perversely, unfortunately, it is much easier to become dehydrated at high altitude. The reduced atmospheric pressure draws moisture from your skin without you even realising it. Our skin is the largest organ in the human body and it ‘breathes’ water constantly.

“At the humidity of sea level, you’re aware when you’re sweating. At high altitudes however, with 0% humidity, the moisture evaporates from your skin without you even knowing. Just sitting at a table eating breakfast, you are perspiring much more than at sea level even through heavy motorcycle clothing, because of course the manufacturers of modern clothing are very quick to point out that their fabrics are waterproof from outside, whilst facilitating the rapid dispersal of moisture from within.

“So it’s very important to drink a lot of water — much more than you would ordinarily consider comfortable. Some guidebooks recommend 5 litres of water per day but we regard this as excessive; 2-3 litres daily generally keeps us out of trouble. But our body can only assimilate about 300ml of water at a time, so don’t ride for an hour then drink a whole litre in one hit as 70% of this will go straight to your bladder and be of no benefit.

“Frequent sipping or small gulps is the way to go. A Camelbak hydration system is ideal but if you don’t have one you must carry a bottle of water with you at all times. You don’t want to find yourself stranded by the side of the road for an hour with no water. Every time you stop for a photo, take a slug of water. Every time you stop for a pee, take another slug of water. Fortunately, bottled water is generally available everywhere we go, even in remote areas.

“How to recognise dehydration? If your urine is strong-smelling or darkly coloured, this indicates a concentration of salts; you are dehydrating. Crank up the sip rate! And don’t go to bed without a bottle of water at hand, because you’ll wake up at 3am feeling like someone’s poured cement powder down your throat.

“Diamox is a synthetic drug designed to counter the effects of altitude, and recently a new drug called Sorojchi (or Soroche) has been getting good reviews. They thin the blood, allowing more efficient transport of oxygen around your body. Some authorities suggest taking them for a few days before you encounter altitude, but we tend not to subscribe to this school of thought.

“Why take a drug unnecessarily if you might not need it? They’re a lot cheaper where we’re going than at home, so we’ll have them available and suggest you keep a few in your pocket, and take one if you feel you are struggling. They are very fast-acting and will give relief in 15 minutes or so.

“We no longer carry bottled oxygen with us. We used to in the early years but found we never needed to use it. Our itinerary is designed to allow us to acclimatise gradually over the space of a few days before we get to the seriously high sections of the tour. All you have to do is ride the bike, smell the roses and enjoy the scenery.”