The 1970s were dark, dark days for Harley-Davidson. After 60 proud years of making great motorcycles and pretty much inventing what a modern motorcycle was, someone decided that it’d be a good idea to take all that heritage, learning, culture and hardware and hand it over to a bunch of corporate suits that had about as much appreciation of Harley and biker culture as Ronald McDonald has for fine dining.

And so the biking world watched in horror as they seemingly tried their best to raize the company to the ground. By cutting every corner imaginable and royally pissing off the entire Harley workforce, the new management may as well just have sold the company to mobsters and blown the proceeds on coke and hookers. And all this was happening right at the very same time that Japan was revolutionising the global motorcycle industry with a bunch of new bikes that quite frankly left most Harleys looking very shit.

And yet Harley survived. But how?

The Good Ol’ Ways

In many ways, the 1960s was very good to Harley-Davidson. They’d spent the last 20 years since the end of WWII both selling a bunch of bikes and luxuriating in a brand following that any company would die for. No matter if you were a New Jersey dentist or a Californian Hell’s Angel, most Americans who wanted to ride motorcycles on the road would have put a Harley on their “must test ride” list. And why wouldn’t they? Harley helped US soldiers kick Nazi arse and were made in the good ol’ US of A. Hell, the only other brand that came close was Triumph, and they were made in England.

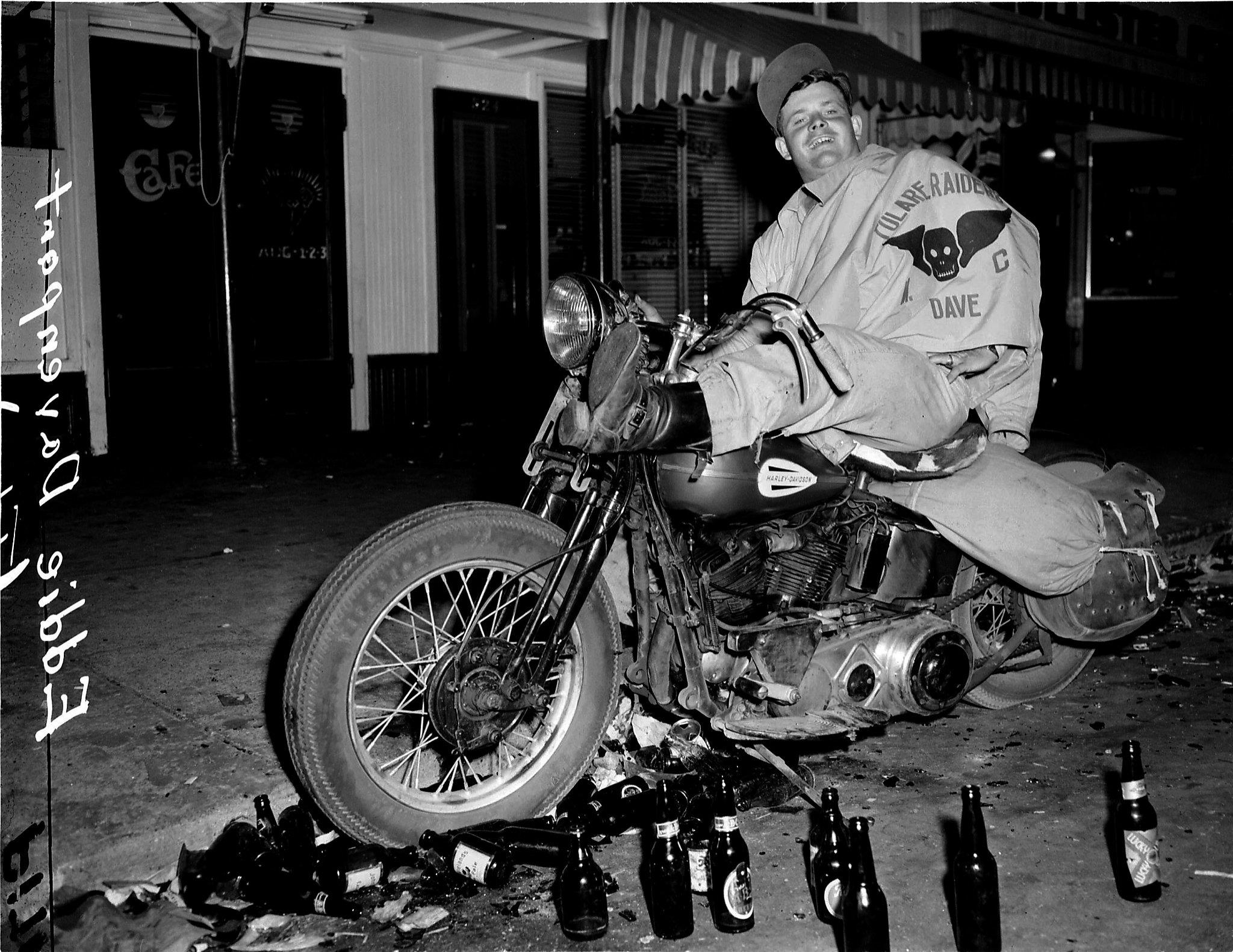

But the rise of ‘The Sixties’ saw a profound cultural shift occur in America. Gone were the gentle, orderly ways of the 1950s, with its buttoned-down conformance and white picket fences. Suddenly men’s hair was long. Music was wild and loud. Drugs were plentiful and clothes were made from rainbows. And by hook or by crook, Harley managed to not only catch this wave, but they rode it all the way into the shore.

Just how you take a motorcycle that was being ridden by cops and soldiers and then make it a counterculture darling just like that is a topic for another time, but against all expectations, Harleys were now totally cool, man.

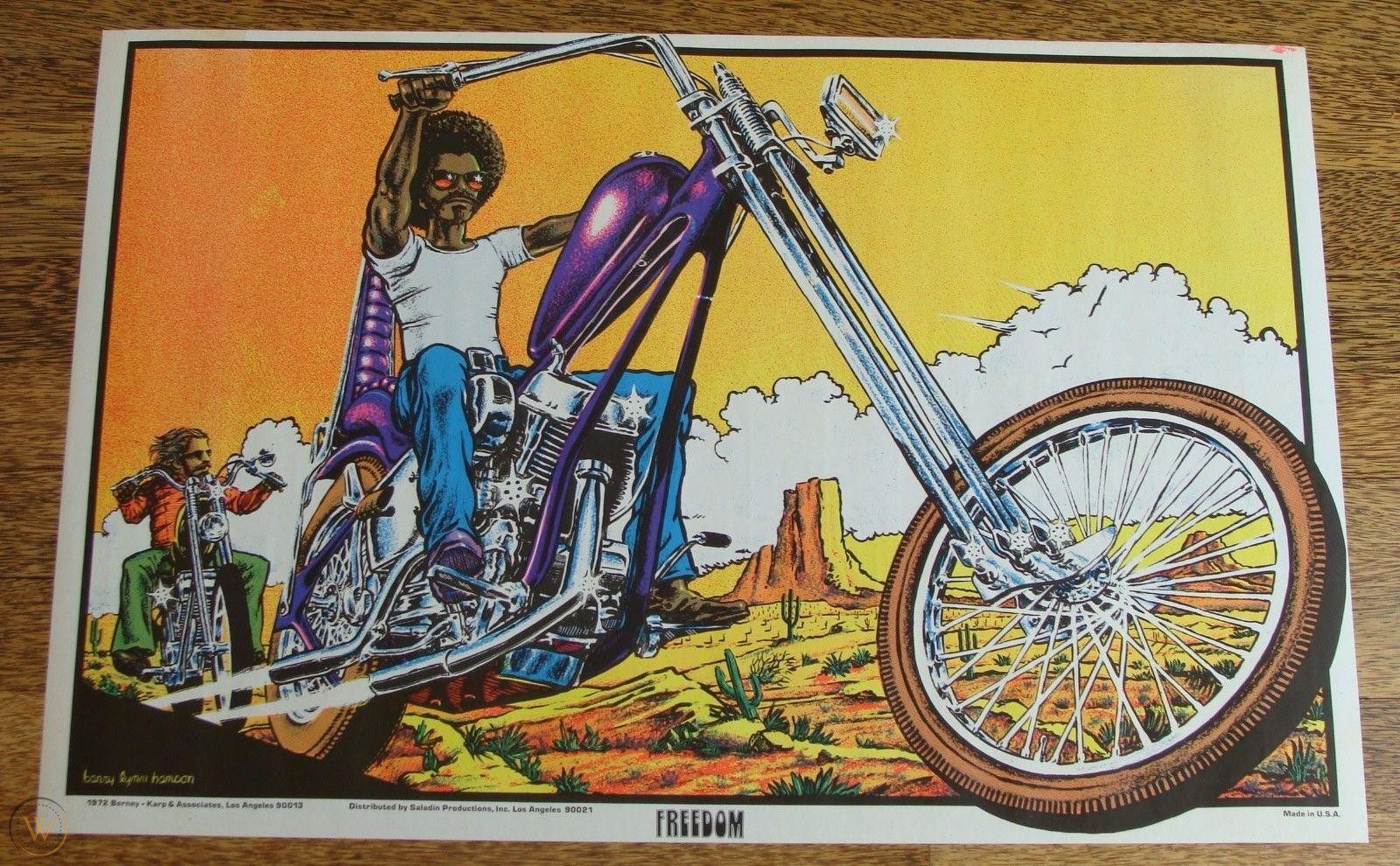

Customisation styles largely helped this; the chopper look that originated in California in the late ‘50s also became a widespread ‘60s fashion, showing many of those attracted to this new youthful rebellion that motorcycles – and in particular Harleys – were just as much at home transporting hippies to music festivals as they were helping cops pull over tipsy little old ladies. The ‘60s were choppers and choppers were forever more chained to the ‘60s. Peace, love and panheads, man.

Brands who gain this type of cultural fandom are like unicorn poop for their owners. It elevates them from the menial task of making shit and selling it for a profit to a level where they really mean something to people. Just like Levi’s means jeans, Apple means iPhones and Coca-Cola means refreshment, Harley now meant cool motorcycles. It’s also important to note that Honda didn’t really mean jack to anybody at this time. Sure, they were made like Swiss watches, but that’s of importance if they don’t make it on rider’s “I really need one of these” lists.

Easy Does It

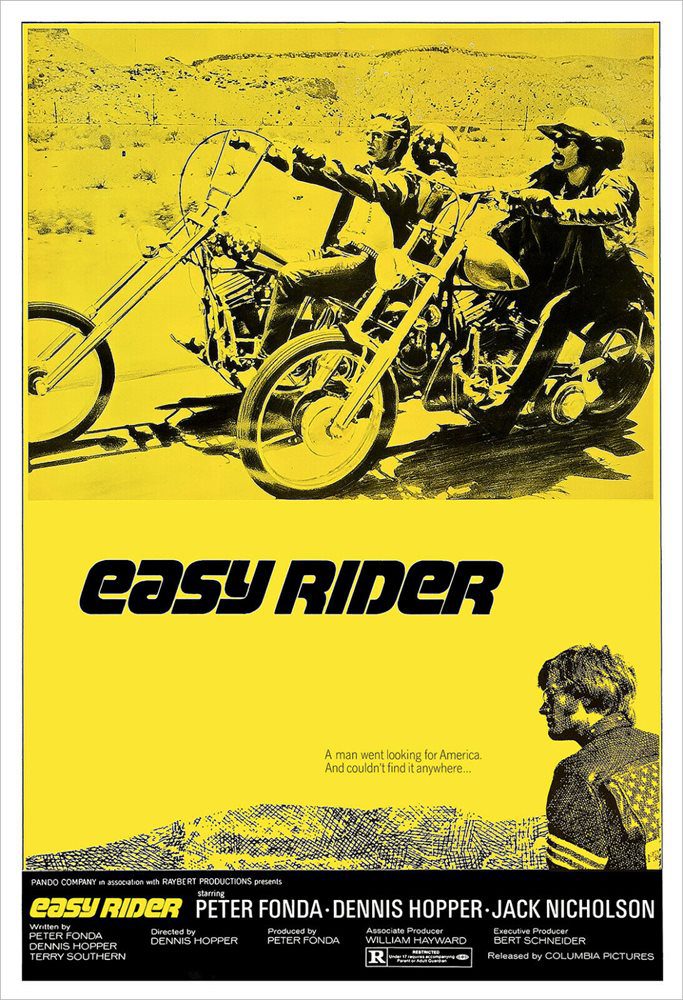

And then came the Easy Rider movie of 1969. Like the Delorean in Back to the Future or the Aston Martins in James Bond, a Harley in a movie like this had almost infinite upsides. As the marketing types love to say, “Money just can’t buy this type of marketing”. It just takes so many variables and coincidences to fall into place for stuff like this to happen, but boy did it happen for Harley here.

And it definitely didn’t hurt things when someone decided that one old ‘50s ex-cop Hydra-Glide should be festooned in the Stars and Stripes. Genius move. Now the hippies and the rednecks were on board. Widespread cult status confirmed.

So like a beacon of motorcycling coolness, Harley-Davidson sailed into 1969 with more ducks in a row than any motorcycle maker had ever had before. Enter stage right, the American Machine and Foundry company of Brooklyn, New York. Even older than Harley, they too were riding high. With connections at the top of the US Government and a list of products longer than the numbers on their top exec’s pay cheques, they were not only convinced of their own amazingness, but they also believed that they could pretty much do anything.

And why wouldn’t they? After all, they’d made everything from remote-controlled toy airplanes to nuclear reactors and ICBM launching systems. Why couldn’t they make a bit more money selling some motorcycles?

But little known to AMF, a storm was brewing. Almost as soon as they’d brought Harley-Davidson, things started to go south for them. Starting in 1972, they began to have trouble with finding stable management and presidents were coming and going like whack-a-moles on meth. Simultaneously, AMF’s middle management were quickly learning that Harley staff weren’t to be trifled with. So while they may have been able to march into companies like Head Sporting Equipment and Roadmaster Bicycles, and pretty much do what they wanted, this definitely wasn’t the case at Harley.

Their ‘our way or the highway’ management style and wholesale cuts across the entire company just made the employees – and their associated union reps – really dig their heels in. Refusing to get their heads around what owning a company like Harley really meant and maybe considering spending some money to modernise its core operations, they simply insisted that they knew best and bulldozed on into the ‘70s.

Hardly Able Son

Soon both Harley and AMF were in dire straits. While AMF’s profits and sales were in a steady nosedive, Harleys were being openly mocked for their lack of performance, quality and exorbitant prices. People now knew that Japanese bikes were better in almost every way than the Harleys.

Those who insisted on still buying Milwaulkee iron were either flag waving patriots, one-percenters, or masochists. But Harley still had one thing going for them that trumped everything else. Mucho cultural cred. And global cultural cred at that.

That bike guy in London that saw himself as a bit of a rebel and had wanted a Harley since he was 5 wasn’t about to let some corporate shenanigans at AMF spoil his fun. Hell, he probably didn’t even know about it. After all, this was 20 years before the internet, and unless you lived in Milwaukee or subscribed to some dull American Manufacturing Industry magazines, the whole debacle would have totally passed you by. And the same goes for Canada, Australia, Europe and the wealthier parts of Asia.

If you wanted a Harley to ride around and pretend you were Peter Fonda, no shits were given about much else. And with the rep that the bikes came with, even quality concerns, piss poor handling, and over-the-top prices wouldn’t have woken you up from your stars and stripes and chrome dreams.

And so, despite the fact that the company was weeks away from bankruptcy and they were making some of the worst motorcycles in their history, the bikes kept on selling. And selling. And selling.

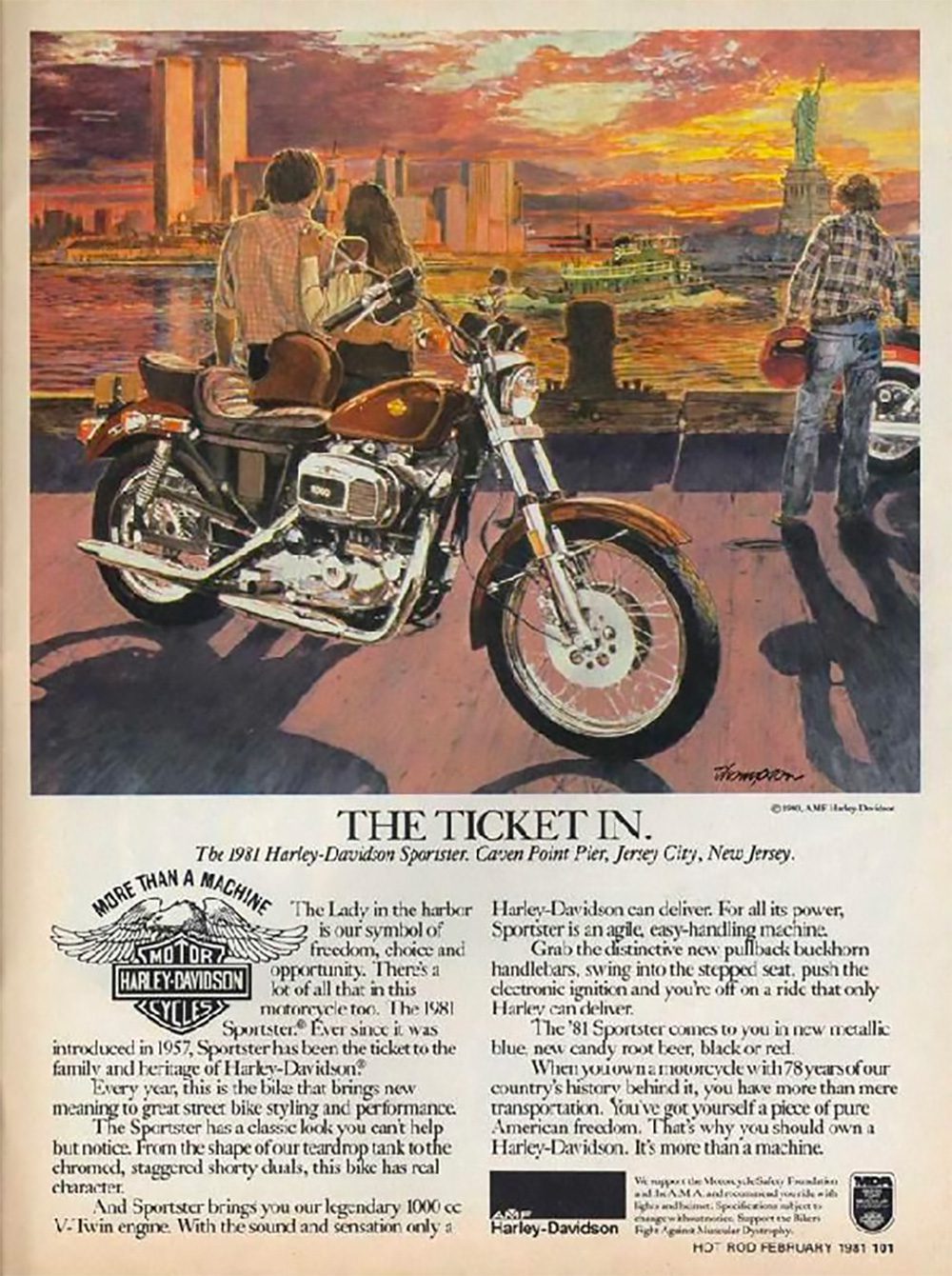

Lucky Thirteen

Then, like some miraculous motorcycle race where the winning bike limps over the line on fire, in pieces and with only one wheel left, Harley somehow pulled victory from the jaws of defeat when in 1981, AMF sold the company to a group of 13 investors led by Vaughn Beals and Willie G. Davidson (the grandson of the original William A. Davidson) for $80 million. Finally, things were looking up for the company. And while they were still to endure some hardships, I think it’s fair to say that they’d looked the grim reaper square in the face, smelt his carrion-scented breath, and yet still lived to tell the tale.

In a sort of final vindication, AMF continued its slide downwards until it was nothing more than a corporate football, being kicked around by a bunch of international sporting goods companies who were no doubt wondering what if anything could be done with it. Screwed in a hostile takeover and stripped of assets, it was left with nothing of any real value bar its widespread collection of bowling lanes and associated manufacturing assets to build bowling equipment. Subsequently, this part of the business was spun off into AMF Bowling which soldiered on in one form or another for the next 20 years.