There is a wise saying about inventions that says that “the invention has to make sense in the world it finishes in, not the world it started.” That quote comes from the founder of O’Reilly Books, Tim O’Reilly, and while it is ostensibly about the rise of the digital age, it applies perfectly to motorcycles.

In the beginning, motorcycles were pedal bikes (or as the British say, push bikes) with a small motor attached that could take over the pedaling for you. That made perfect sense in the early 19th century, before the automobile rose to popularity. Once the automobile started to make its lasting impact on history, motorcycles morphed from being what we now call mopeds into dedicated, purpose-built machines. It took quite a few tries to get it right, but then names like Royal Enfield, Harley-Davidson, Indian, Norton, and many others started to carve out their own niches.

The thing about all these bikes, however, is that while they were amazing inventions, they didn’t really make much sense outside of some very specific uses. They began to make more sense after World War II, as Harley-Davidson had supplied patrol bikes for overseas forces, and their ruggedness and size meant that they could get places quickly that larger vehicles could not. It was, in fact, Germany that inadvertently helped create the wheels that moved history.

The Origins of the Super Cub

Honda Soichiro and his business partner, co-founder of the Honda Motor Company Fujisawa Takeo, were touring Europe, promoting their new company, motors, seeking distributors, and eventually ending their tour by entering Honda racing motorcycles into the Isle of Man TT race, when they happened to visit Germany in 1956.

Honda, who was as dedicated an engineer as you could possibly get, and Fujisawa, the salesman and money man who fulfilled a role that we would call Chief Financial Officer today, witnessed the German populace enjoying small, lightweight motorcycles and mopeds, using them for everything from travel to going to the corner store for groceries.

It had actually been in Fujisawa’s mind for a while that in the post-war economic boom surging through Japan and parts of Europe, a high-performance but small motorcycle could be exactly what densely packed cities needed. In a marked change of pace compared to other Japanese manufacturers, he didn’t simply want to increase the number of larger, more powerful, and more expensive motorcycles being sold, but target a market that many (except the Germans) seemed to be missing out on.

His thought was that as the world rebuilt from a devastating war, bicycles were naturally the starting point for travel. As the economy recovered, people would then buy a clip-on motor to make their bicycle a moped, then move on to scooters and finally small cars.

Dedicated motorcycles didn’t enter into that upgrade path because the bikes of the day were sometimes as expensive as a new car. It took a lot of convincing for Honda, who simply wanted to build engines and go racing on two or four wheels, to see that there was a ripe market for a small but high-performance motorcycle that was inexpensive, technologically simple, reliable, and efficient.

Honda was, at the time, a very popular company, with their automotive and scooters selling well, but they were at a turning point. They needed a mass-market item—something that would stamp the Honda Motors name into the history books—and so design work began on what was originally just called “The Cub.”

Fujisawa is quoted as famously giving Honda the requirement that if he could design a motorcycle that could hide all the wires and tubing under the seat, was reliable, powerful, and could be ridden with one hand while carrying a tray of soba noodles in the other hand, he could sell it. Honda accepted that challenge, and began pulling development from all of the projects he had engineered.

From the Juno scooter, fiberglass reinforced plastic was used to create leg fairings. The high performance 50cc single-cylinder four-stroke engine from the lightweight class of race bikes for the Isle of Man TT became the beating heart of the Cub, providing 4.5 HP.

The frame would be made out of steel, but in a stroke of genius, the entire spar from the front forks to the rear mudguard holder was one continuous piece of metal, negating the need for complex welds. It also didn’t need a clutch lever—while it did have a sequential three speed gearbox, it used a centrifugal clutch that would disengage if the revs were high enough when you requested an upshift, then change gears and automatically re-engage as you came off the shifter.

The finishing touch was that all the electronics and all of the oily bits were, as Fujisawa had set the challenge, underneath the seat and hidden away. It was extremely simple to maintain, as the entire engine could be dropped out by undoing just three bolts. The chain was also hidden behind a full coverage chain guard, keeping even that oily bit out of sight, which could be removed by undoing a clip, one bolt, and giving it a good tug.

It was introduced to the world in 1957 at motor shows, and especially around smaller industry conventions in Japan—and to say that it landed with a thud is understating the fact, as the recession left behind by World War II was just starting to recover. The newly named Super Cub C100 still went on sale in 1958, however, and sold decently, but it wasn’t the mass market adoption that Fujisawa had envisioned.

Three months after the first motorcycle rolled off a dealership lot, complaints started to come in that the clutch on the Super Cub was slipping. It was approaching a Japanese national holiday week, and both Honda and Fujisawa knew that they needed to fix the issue immediately.

As the saying goes, the best advertisement is word of mouth, and as many traveled across Japan to visit friends and family, bad public relations could not only mean the death of the Super Cub, but also cast doubts on whether the Honda Motor Company actually supported their products.

As such, during the national holidays, everyone that worked at Honda, quite literally everyone, from salesmen to secretaries, factory workers to even Honda and Fujisawa themselves, gave up their holiday time and were instead sent out in a PR move of military precision. Honda had found the issue and changed the design of the bike slightly, but the already-sold Super Cubs would need to have new clutches put in and a small part to fix the issue.

In a testament to just how easy the Super Cub was to repair, during that one week holiday period, every single customer that owned one of the bikes was visited personally by a Honda Motors employee who would repair their bike right then and there, free of charge.

The PR impact of that move shot Honda Motors way, way up the consumer satisfaction metrics, which approach near mythical status in Japanese culture. It was no longer “my Honda motorcycle was built poorly and has a slipping clutch”—it was “Honda Motors came out and fixed my bike, for free!”

The Wheels that Liberated Asia… Quite Literally

The news that Honda Motors not only had an inexpensive, highly efficient and powerful lightweight bike for sale, but that they stood behind their product and proved how easy it was to fix spread around the world. All of a sudden, markets that had shown no interest in the Super Cub were suddenly asking about distribution deals and opening of Honda showrooms and dealerships.

The only country that didn’t seem all that bothered to join in on the excitement was the United States, as Indian and Harley-Davidson, in their cruiser war without end, along with some imported British bikes, had saturated the market.

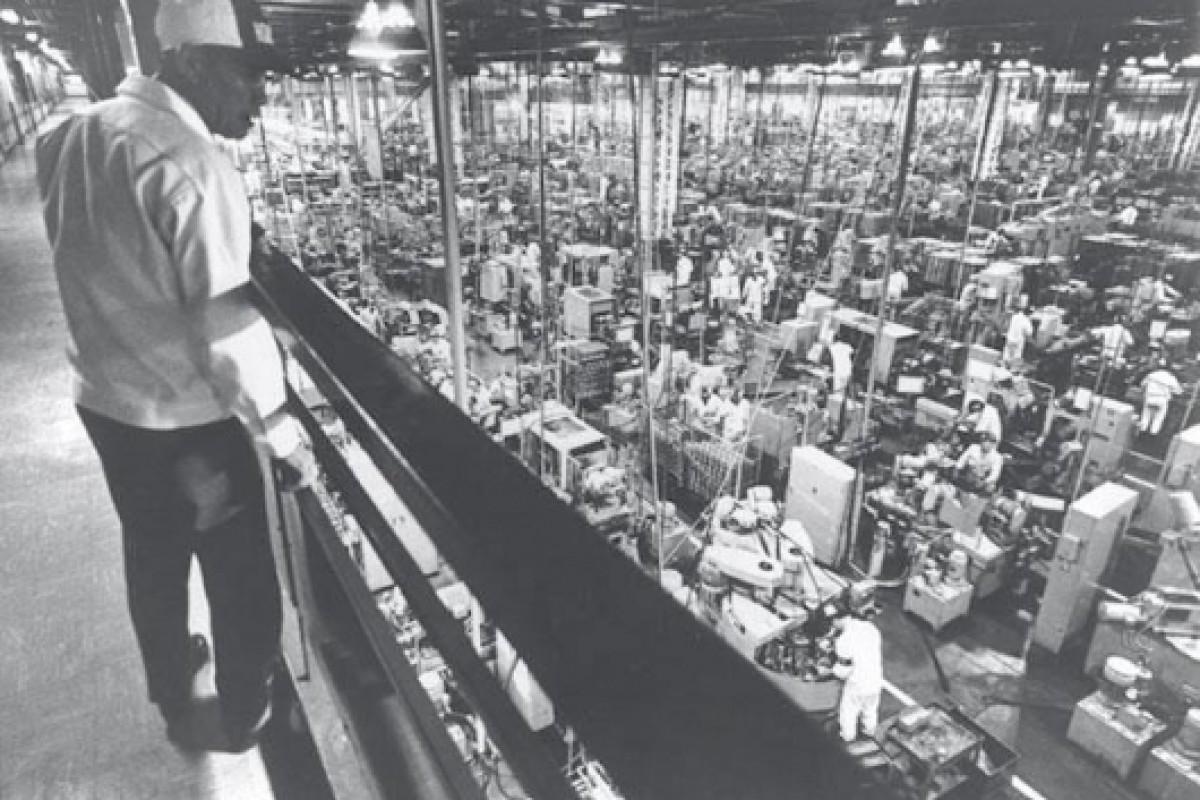

The demand became so high, in fact, that Honda Motors built an entire factory dedicated to the production of the Super Cub in Suzuka, Mie Prefecture. At a cost of 10 billion yen, or approximately $443,140,000 USD in 2022, the new factory was modeled on the VolksWagen Beetle production facility in Germany that Honda had seen just two years prior.

It was built to produce at first 30,000 Super Cubs per month, and started operating the moment the main production line was completed. That number rose to 50,000 Super Cubs per month once the secondary production line and the whole factory was finished.

However, it seemed that Honda might have jumped the gun by dumping so much cash into one production facility. While the demand was high, the avenues of distribution were taking longer to establish.

For each country that wanted to import Super Cub, government approval, permits, taxation and tariffs all had to be negotiated. This proved to be such a delay that the Suzuka factory almost ran out of room to store finished Super Cubs. Some industry analysts at the time even said that the expenditure was too risky, and for most of 1959, it seemed to be true.

When all those distribution and import negotiations were finished, however, Honda Motors received a massive return on their investment. Super Cubs were quite literally leaving the end of the production line, ridden out the factory doors to the inventory parking space, and by the time their engines had been switched off, they had been sold.

The biggest factor driving this once-in-a-generation sales boom was that Fujisawa’s initial concept of an inexpensive, high-performance motorcycle that could be fixed with a hammer and a rock caught on in Asia. During the 1960s, much of the Asian continent, especially in the Southern regions, was coming out of colonial occupation, or were developing nations where cars were simply too expensive of an item to own.

When the Super Cub came along, it was an attainable vehicle that suddenly opened up the possibility of intercity travel not requiring several days, and of efficiently moving around town to be able to free up more time to actually do things.

Countries such as Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, and Thailand were suddenly bursting at the seams with the Super Cub, and revolutionized the delivery driver concept across all those countries as Fujisawa had set the goal of the motorcycle needing only one hand to control, leaving the other hand free to carry delivery items.

If it broke down, replacement parts were dirt cheap—something especially important in developing nations—and instead of having to take it to a repair shop, you could fix your own bike by the side of the road.

No other motorcycle in history has ever come close to the impact that the Super Cub had on one of the most populated parts of the planet. Within the decade, the entire culture of many countries shifted from being isolationist, separate villages and towns and maybe visiting a city once in a lifetime, to liberating untold millions of people to make a day trip to the big city and be back in town before the sun set. What had once been something that people had only read about happening in the “rich nations” like the UK, parts of Europe, and North America was now something very real in their own part of the world.

This explosion of popularity was again down to Fujisawa, who may go down as one of the best sales managers in history. He had the Honda marketing department place ads for the Super Cub in every newspaper, general interest magazine, in the back of shopping catalogs. He made sure that instead of targeting the niche rider market, he targeted the general market, those that would never pick up a motorcycle magazine in their wildest dreams.

The other stroke of genius he had was speaking to the culture of the Super Cub, not only its technical specifications. Instead of the ads stating “50ccs of Earth-churning power,” they stated “Wouldn’t you love to be able to visit your mother more often?” or “What would you say to a motorcycle that lets you go to the market in the city down the road and be home in time to cook for your family?”

By making the core of the ad campaigns the issues of the time, the Super Cub became the liberator of the Asian continent—and even today, nearly 40% of all new Super Cubs being made go to Asia.

Built Since 1958: The Best Selling Road Vehicle of All Time

Some cars have a reputation of being sold at a prodigious rate. The VW Beetle comes to mind, as well as the Ford F150, “the truck that built America.” However, if you combine the total number of VW Beetles and Ford F150s ever sold (23 million and 41 million respectively for a total of 64 million), that still pales when put next to the Super Cub.

As of 2017, the Super Cub had sold a nigh unbelievable 100 million units. It is very likely nearer to 110-120 million in 2022, and it is safe to say that Fujisawa’s and Honda’s desire to have a mass market product that would leave its mark on history has been attained 100 million times over.

The Super Cub hasn’t just affected the motorcycle markets either. Riding the popularity of their engines being ultra-reliable, Honda stormed the US, UK, and EU markets with their cars, including the S600 and S800 Roadsters. These were sold as efficient, fun little sports cars, sedans that were comfortable and could easily handle a family of four, and entry-level cars that someone in their first couple of years of working in the real world could afford without breaking the bank.

It is quite safe to say that with the Super Cub, another one of Honda’s most dominant vehicles was able to come to life. We are, of course, talking about the Civic. Even today, in 2022, the Civic is to a recent college or university graduate in North America as the Super Cub was to the Asian continent in the 1960s: affordable, easy to fix with a hammer, and reliable for getting you from point A to point B even if you abused the hell out of it.

The Lasting Legacy of the Honda Super Cub

What is astounding is that the Super Cub is still a desirable motorcycle in many markets that scoffed at it or shunned it during its first export years. In the UK, it is one of the best selling runabout bikes for for those that have just obtained their A1 motorcycle license, and its now-iconic plastic leg fairings keep your pants dry when it rains (which happens a lot in the UK). In Europe, where the retro-styled scooter is the more chic option for two-wheeled travel, the Super Cub has a timeless classic style that never gets old.

We could go on listing why the Super Cub is still a sales leader today, and why Honda has cashed in on the fun of small motorcycles with their miniMOTO line of the GROM, Monkey, and Navi, but it would just be the same reason over and over. It was the right bike, at the right time, in the right place, to liberate Asia and introduce reliable, efficient motorcycles to the world. The only issue that is even possibly going to affect it is the current push towards electrification of vehicles.

An Electric Future? What the Next Decade Holds for the Super Cub

Much as the Super Cub revolutionized history when it appeared in 1958, the EV Cub is set to revolutionize electric motorcycles. In a market that has seen many promises, some bikes, and a lot of wondering where all the electric bikes are, Honda is steadfast in proving that electric motorcycles and scooters are the way of the future for two wheels.

Part of this strategy was finally signed and certified earlier this year, when Honda, Yamaha, Kawasaki, and Suzuki all officially adopted the same standard for electric motorcycle batteries.

The core idea is that at gas stations and charge stations as they are now, there will be a wall of batteries with an easy to grab handle. Instead of having to plug your bike into a supercharger or the wall at home, which will still remain options, you simply park your electric scooter or motorcycle, lift the battery out, go to the wall, pull a fully charged battery out, place your drained battery in the now-free cubby, and slide the charged battery into your bike—then off you go.

This system is already up and running in Japan, where it is known as Gachago. The Honda Benly-E scooter, which can hold two of the swappable batteries for extended range riding, is now the default vehicle used by the Japan Post Office to get to places where cars simply will not fit. It is expected that by the end of 2022, a battery swap version of the PCX maxiscooter, the EV Cub, and the just-announced, Japan-only Gyro-e will be on the market in the island nation.

There is also ongoing research by all of the Big Four into sustainable fuel, as motorsports series under the auspices of the FIA and FIM have set targets to have 100% bio-ethanol generated from sustainable non-food sources by 2026.

Motorcycle engines as they are today don’t like ethanol-hydrocrabon mixtures in general, which is why no bike on sale today can run on E85 unless it is modified heavily. With the trickle down effect of motorsports to the mainstream, however, we might have the EV Cub and the Super Cub Bio-Fuel by 2030.

All we know is, there is no way Honda will ever stop making the motorcycle that stamped their name into history. Nor should they.