The explosion in popularity of cafe racers over the past 10-odd years was a challenge to Australia’s old-school motorcycle journos in more ways than one. Seeing the existential writing on the wall for their typewriters and booze, they began to snipe willy nilly at the new kids on the block. Their hipster fashions. Their questionable riding abilities. Their lack of alcoholism. It was all fair game for the soon-to-be-extinct species, but nothing crystallized the generational differences quite like the young whippersnapper’s love of the Honda CX500.

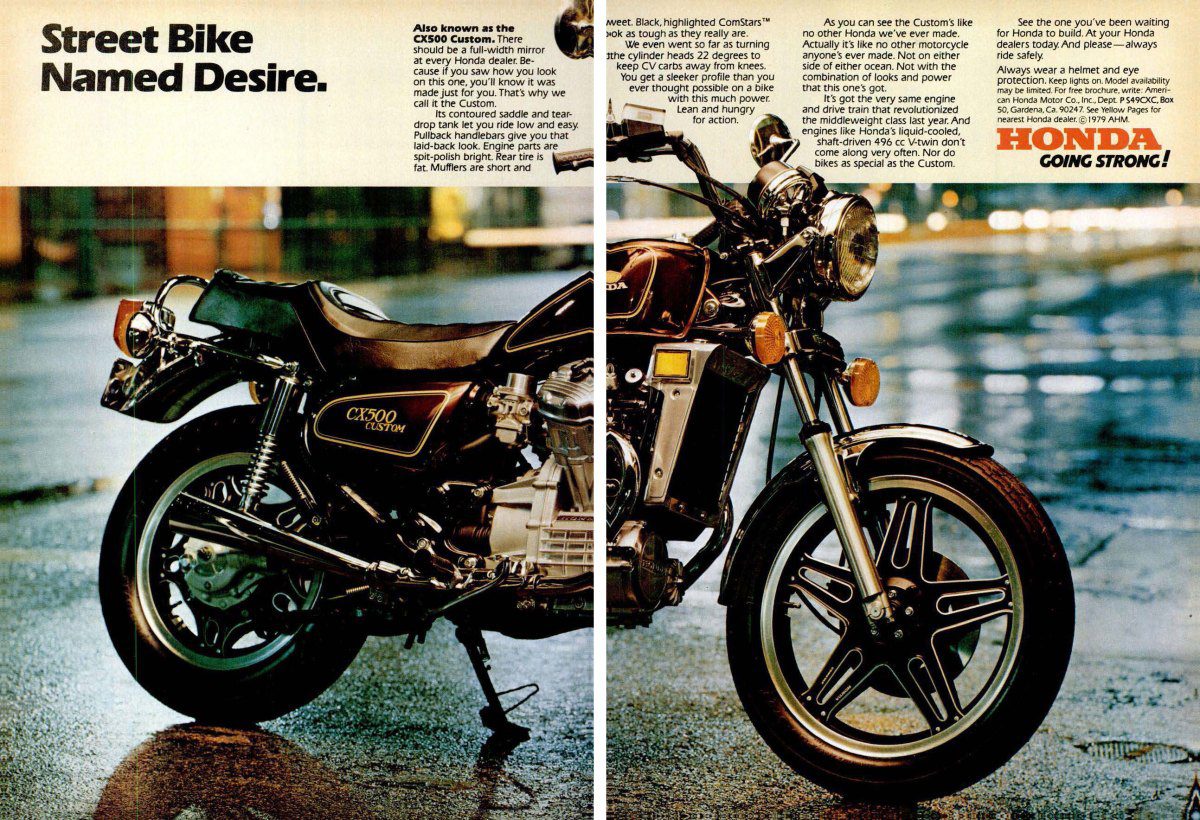

As a base for a 21st Century cafe racer, they were a great bike. Cheap, brutally reliable, and offering a v-twin engine that had a whole bunch more appeal than Honda’s vanilla twins or in-line fours. They were a little – dare I say it – Italiano in their vibe. And so without a clue as to the history of this much-maligned Hamamatsu ‘horror’, off the kids went to make some of the scene’s best custom bikes. But why were the bikes so hated in the first place by some Aussies, and was it really deserved?

The Tortoise and the Hair

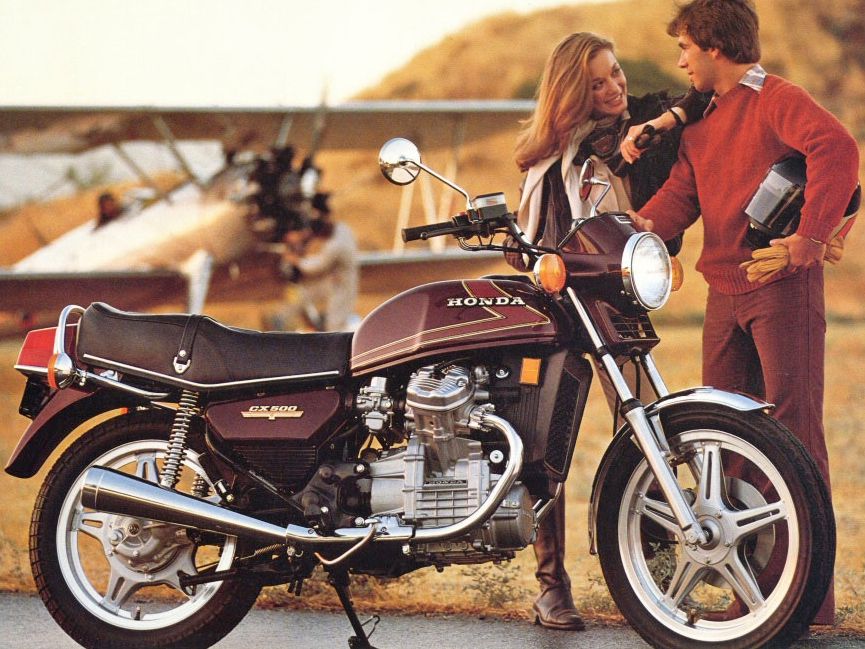

First revealed in 1978, it would be a gross understatement to say that the CX split opinions. But to really understand why, you have to transport yourself back to Australia in the 1970s. As a culture dominated by men, beer, and sport, riding a motorcycle was still seen as quite the rebellious act. And not rebellious against the dominant mustachioed paradigm, but – if it were actually possible – towards it. Only a man’s man rode a bike in public back then. Real men and proper outlaw bikers. Then along comes this uppity Japanese motorcycle company with the balls to not only make bikes that didn’t break down but to also dare to release a v-twin. Didn’t Honda know that v-twins were sacred?

Journos both locally and overseas were clearly befuddled by the bike. Its lack of horses and plain looks really didn’t help matters. Neither did the fact that globally, Hondas were selling like hotcakes and that the company’s production figures were through the roof. So in a response belying their own biases and predilections towards the hairy-chested Italian sports bikes of the era, they condemned the CX500 as an overweight and underpowered flop with a perceived lack of sex appeal, no doubt further damaging their already questionable chances in attracting the local sheilas.

Bike of the Year

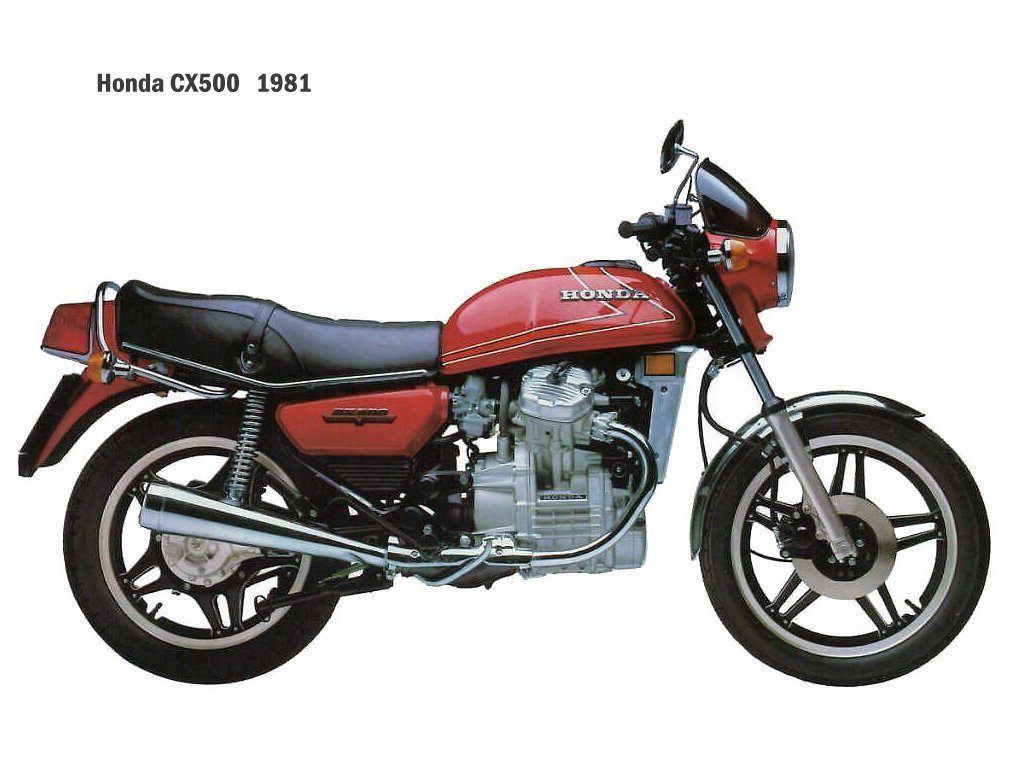

Cam chain tensioner and big end issues sprung up early in the model’s life cycle, adding fuel to the CX doubter’s fires. Quickly rectified by dealers, the general public was not perturbed and the bike’s comfort, handling, adequate performance, and refinement were traits that shone through during test rides undertaken by potential owners. It should also be said that not all the media at the time were negative about the bike. Indeed, Wheels Australia made it their Bike of the Year in 1978, no doubt in part to ruffle a few old-school feathers.

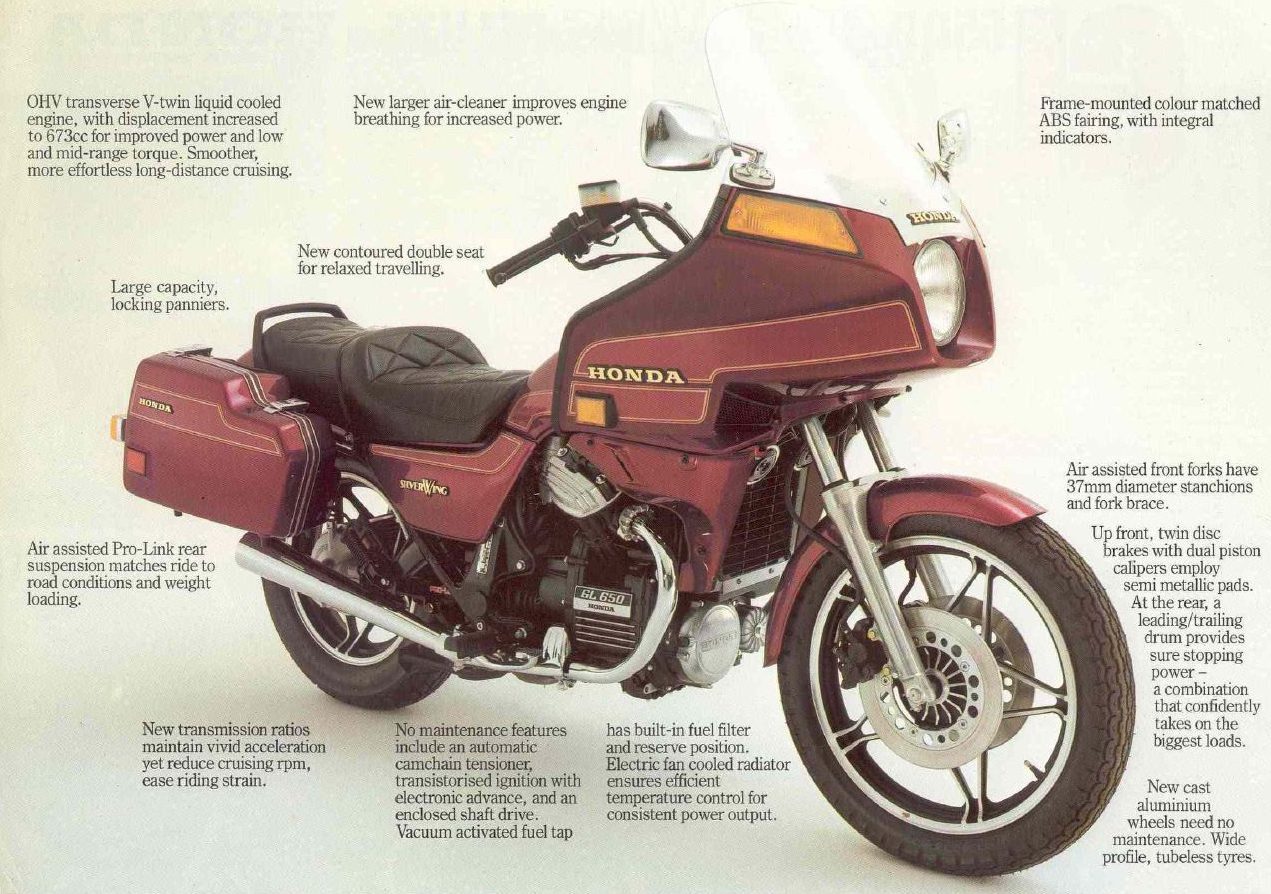

But why ‘Plastic Maggot’ you say? There’s no doubt that on paper, the bike did look rather slow. With 200-odd kilos (441 lb) wet and ‘only’ 50 horses, it was most definitely not going to pull your arms out of their sockets. And Honda saw fit to repackage the platform in a few faired variations that were quite generously clad in Japan’s best injection-molded tech. Notably, there was the GL500 ‘Silver Wing’ with its panniers and full front fairing, along with the most famous of all the CX models – the CX500 Turbo – with its undeniable 80s aero cladding and plentiful go-faster stripes.

World’s Fastest Maggot

Once the dust had settled and the macho Aussie bike journos had turned their questionable attentions to other anger-inducing topics like feminism and cirrhosis of their livers, the CX would soldier on like so many of its brethren. Fed a regular diet of oil, plugs, and tires, the bikes became the favorites of couriers both locally and in the UK, where stories of CXs exceeding 200,000 miles (320,000 kilometers) were not uncommon.

And there’s even a turbo CX500 that set a 141 mph (227 kph) land speed record at Bonneville in 2017. As Lucas Anderson, the bike’s owner stated in 2017, ‘We have beat on and abused that engine for years and it still keeps running, and it has three land speed records under its belt. The engine that was in the bike for the record runs is the original engine that came with our bike in 1979, which I think is pretty cool.’

The moral of the story is one as old as time itself; only fools judge books by their covers. For as underwhelming and unexpected as the CX Honda may have been, it went on to sell over 300,000 units in all its various 500 and 650 guises, proving the critics wrong and the Honda engineers so very right. But that’s not to say that Honda didn’t learn from the CX. For them and their engineer-led design processes, it was an important lesson in ensuring that bikes not only had superlative engineering but that they also looked the part. Enter stage right Honda’s VF1000R in 1994 and the start of the world’s next big moto obsession – sportsbikes.

Read more on custom Honda CXs here.