Like many teenagers in 1980s Australia, I was a willing participant in the Japanese rotary-engined street racer phase that swept the country at the time. Hell, there was even a magazine called Fast Fours & Rotaries that sold here like hotcakes.

But for me, the whole thing crystallized when my mate Daryl rolled up in a red Mazda RX-3 one weekend while I was still in high school. Now, I’d heard about what these rotary engines were capable of, but I wasn’t really prepared for what was about to happen. Not at all.

Fast forward 20 minutes later. I’m in the passenger’s seat, and ‘Dazza is’ behind the wheel at our first set of lights. Things had been pretty sedate up until now, but the moment the lights went green, Dazza stood on the go pedal, and all hell broke loose. I was—for the first time in my life—unable to keep my head straight and my eyes forward while accelerating, thanks to the g-forces that this very humble-looking car could pull.

Though I tried to fight it, I ended up with a shocked look on my upturned face and a set of eyeballs that were having serious issues seeing over my cheeks. Welcome to the wonderful and frightening world of the Wankel rotary engine.

First Things First: What Is a Rotary Motorcycle?

First and foremost, I’m guessing that there may be a few of you who don’t know just how a rotary engine works—or even what it is. So here’s a little backstory.

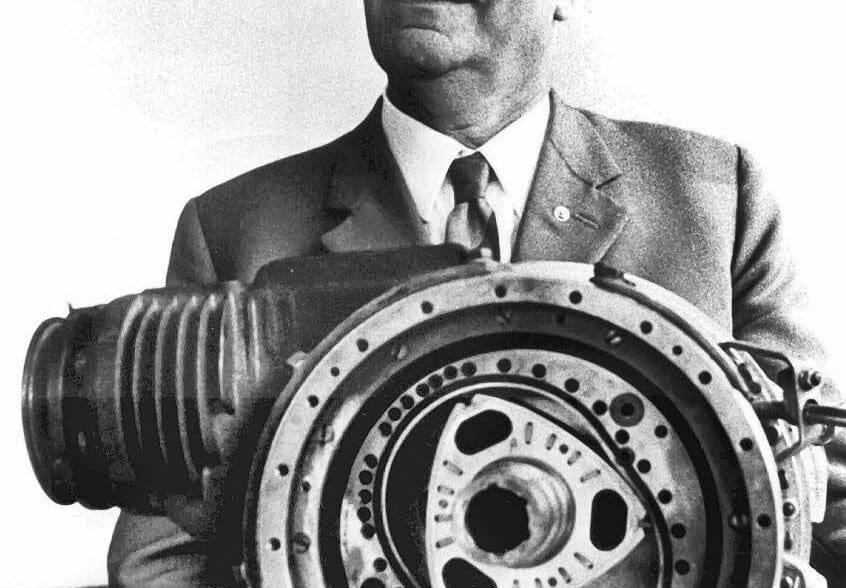

Originally conceived by Dr. Felix Wankel (no laughing up the back, please) in Germany in 1929, the Wankel engine ‘is a type of internal combustion engine using an eccentric rotary design to convert pressure into rotating motion. Compared to the reciprocating piston engine, the Wankel engine has more uniform torque and less vibration and, for a given power, is more compact and weighs less.’ Thanks, Wikipedia.

Despite all these ticks, it took the design a leisurely 20 years to make it into production. And you can crank that figure up to 30 years if you are only counting motorcycles.

The First Rotary Motorcycles: Not So Rad

Early rotary-engine bikes were not what you might expect from quintessential vintage motorcycles. The first rotary-engine motorcycle was the East German, ‘never made it past the testing stage’ KKM 175W motorcycle for the Motorrad Zschopau IFA/MZ factory in 1960. Looking to replace the flat-twin two-stroke smokers they were relying on then for both bikes and the infamous Trabant 3-cylinder two-stroke cars, the rotary with its compact size and impressive power output seemed perfect.

Despite my frothing opening salvo about how rotary engines can tear you a new one, I’m somewhat miffed to say that early rotary bikes weren’t the speed-of-light missiles you might expect—especially if you’re used to riding ultra-fast street motorcycles. And boy, were they thirsty; it’s a common complaint of the design (along with the engine’s ability to blow through gaskets like they were beers at a salted peanut-eating festival). Oh, and the engine’s torque figures tend to be pretty underwhelming.

Whatever their downsides, though, the romance between these engines and motorcycles was a long and glorious one. As further proof of this, the next bike to be handed the Wankel torch was on the other side of the world, at the Yamaha Headquarters in Japan.

Rotary Motorcycles in the Early 70s: A Biscuit Tin That Spins

Licensing the rotary design in 1972, The Iwata giant fabbed up a prototype for that year’s Tokyo Motor Show called the RZ201. Once again searching for two-stroke alternatives, the company claimed around 70 bhp for the 220kg (485 lb) bike; better than their East German brethren but still no screaming bullet. Sadly (you’ll notice a real trend here), they never took the idea into production and eventually shelved it.

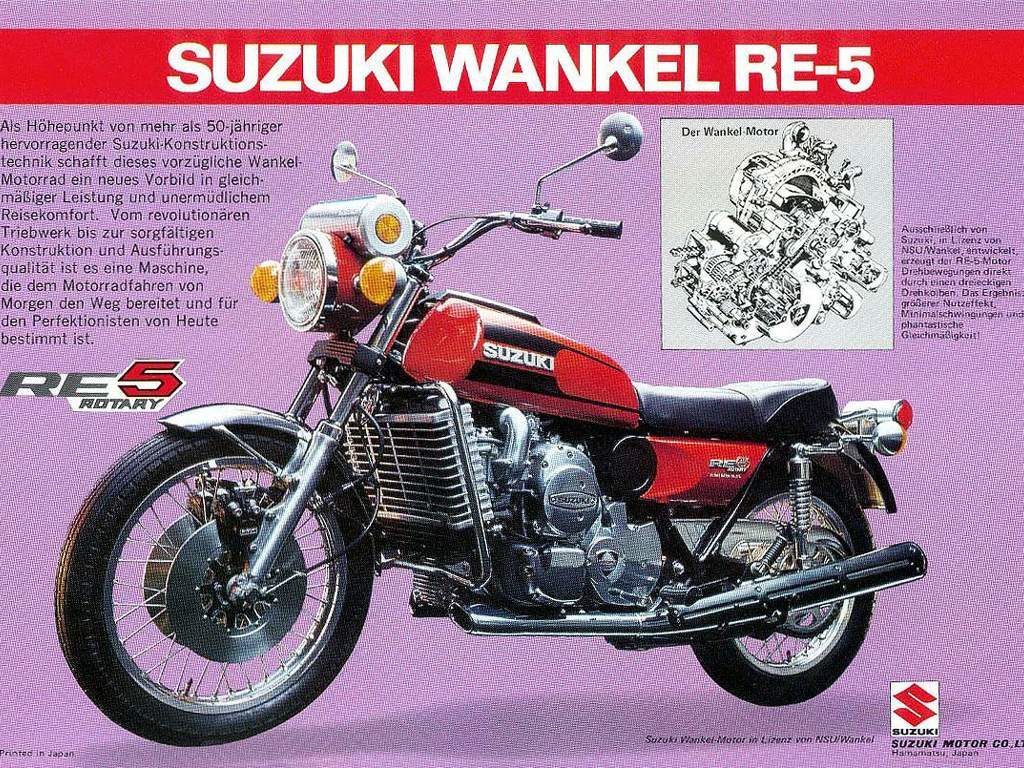

Not to be outdone, Suzuki also got wind of the rotary idea. But this time, they actually delivered. For the 1973 Tokyo show, they revealed the RE-5, probably the world’s best-known rotary motorcycle. The Wankel engine design Sukuzi settled on here was a single rotor, water-cooled spinner that put out about 60 ponies.

And despite the garage door radiator and the rotary engine, the design feature that somehow steals the show on this model is that insane rotating biscuit tin instrument cluster. I’m not quite sure if it’s the best or worst piece of moto design I’ve ever seen. Whatever the case may be, it certainly isn’t boring.

Late 70s Rotary Motorcycles: Der Muskelmann

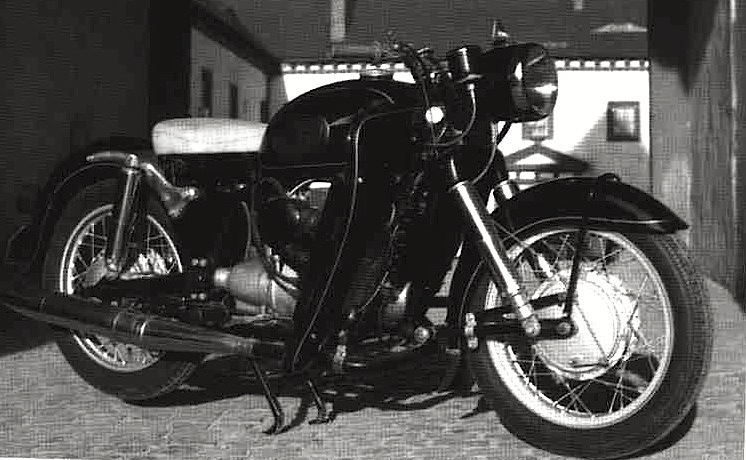

The Germans kept tinkering and ultimately returned to the rotor limelight with the Hercules—aka the DKW—at around the same time as Japan. With much less power than the Suzuki, it nonetheless was made in much larger quantities and was sold all the way through to 1977.

A classic small motorcycle with a 300cc engine and only 20-odd-horses, it was again really quite sedate. Not a sales success, it still managed to sell in decent volumes, no doubt thanks to the German’s love of new tech and the engine design being seen as a German engineering breakthrough.

Personally, I love the look of the engine; it really does sell the idea of the powerplant being all-new, and it would have surely gone down well as a talking point in Sunday ride car parks.

Fearing they might miss the boat on some new breakthrough, almost all of the then-dominant manufacturers—including Kawasaki, Honda, and BSA—got in on the action. After all, this was clearly the future! But in an interesting display of their own conservativeness (or should that be common sense), most corporate engineers made calls to pull the pin on any further rotary developments.

Of course, Mazda took the plunge in as big a way as they possibly could. Leaning into the idea with some serious commitment, they would eventually develop the Le Mans-winning 787B racer that would win that prestigious event in 1991. But that’s a whole different, and non-motorcycling, story.

Rotary Motorcycles in the 80s & Beyond: Smoke ’Em If You Got ’Em

No doubt bolstered by Mazda’s commitment and the thought that rotary engines were tiny powerhouses just waiting for a decent engineer to set them free, the end of the 70s saw Norton take control of the smoking, buzzy torch and push ahead. Their first commercial release was based on test mule bikes they supplied to police. Their 1987 Classic was powerful, fast, light, and properly reliable, clearly making some giant leaps in the development phase.

Seeing the potential here, Norton doubled down and produced what is often referred to as the pinnacle of rotary motorcycles, the John Player Special-branded F1 in 1990. With 95 hp and water cooling, the world finally had a rotary motorcycle that proved just what rotary engines could deliver when the engineering and design stars aligned. This was proven when they took out the British Moto F1 Championship—hence the bike’s nomenclature.

Their final flourish in the space was the early 90s F1 Sport, which was a true refinement of all that Norton had learnt. The bikes were expensive at the time and are still much cherished by Norton enthusiasts the world over as a kind of testament to what British know-how could achieve despite powerhouse countries like Germany and Japan trying the same feats and not quite hitting the mark. Rule Britannia, much?

Many thanks to the studious research of Paul d’Orleans from thevintagent.com.