The History of the BMW GS-Series

It’s hard to believe that it’s been 30 years since BMW introduced a radical new motorcycle to the public. The original BMW R 80 G/S received a “love it/hate it” reaction from everyone who laid eyes on it, and not a single person thought the concept would succeed.

But here we are, 30 years later and the GS-series is not only one of BMW’s best-selling models, it has spawned an entire new motorcycle segment called “Adventure Touring”.

This is the official BMW history of the BMW GS-series, along with a special 49 photo slide show with rare images of GS versions through the years. It’s a great story and we hope you enjoy it as much as we did!

1980: A New Era in Motorcycles

The BMW team were all smiles as they presented the brand’s new production motorcycle at the IFMA international bicycle and motorcycle show in Cologne in September 1980. Here, under the critical eye of industry experts and the astonished gaze of visitors, it was clear that the BMW product developers’ latest creation had hit the bull’s eye.

The brand new R 80 G/S – a bike designed to offer fun in spades with its ability to both dive through the corners and clock up the touring miles – saw BMW Motorrad buck the established trend at the time towards specialist machines.

The G/S in its designation referred not to “Geländesport” (off-road sport) but rather to its “Gelände/Straße” (off-road/road) crossover skill set. 30 years ago the idea of the universal-use motorcycle appeared to be dead in the water. Clearly defined parameters of engineering and design were setting the tone for the mass market, but BMW resolved to swim against the tide.

The Munich-based company created a new breed of motorcycle with the R 80 G/S, one designed to reverse the prevailing trend. The boldness of the BMW decision-makers was to be rewarded with a wave of success which has now endured through three decades and shows no sign of petering out.

The R 80 G/S was the first volume-production machine to offer respectable off-road capability without asking customers to compromise when it came to road riding, touring and everyday practicality. Up to that point, motorcycles on which two people could travel in reasonable comfort were restricted to the established road network.

At the other end of the scale, if you wanted a motorcycle that could handle Alpine gravel paths, Tunisian desert tracks and the sandy roads of the Finnish tundra, you would have to make do with a stripped-down off-road machine lacking touring ability, on-road performance, range and ride comfort.

Although growing in numbers by the year, the legions of two-wheel touring enthusiasts were forced to make do with stopgap solutions and unsatisfactory compromises. That was until BMW introduced the R 80 G/S, a new landmark in motorcycle design for both on and off-road use.

BMW’s new boxer model offered the first convincing evidence that off-road capability, a high degree of active safety, cornering fun and touring comfort for two people and their luggage could be brought together in the same machine. The R 80 G/S paved the way for this new breed of “Reiseenduro” (touring enduro) motorcycles to conquer roads and showrooms around the world.

The Origins of Travel and Adventure

The German term “Reiseenduro” is an amalgamation of two nouns. “Reise” is a Germanic word originally meaning not only a change of location, but also “to stand up” or “to rise”.

The word “enduro”, meanwhile, has its roots in a Romance language; the Spanish “duro” (“tenacious” or “dogged”) also makes an appearance in the English verb “to endure”. A “touring enduro” is therefore a motorcycle with which you can set out for faraway destinations and reach beyond both your own limits and the boundaries of the familiar.

BMW still represents the benchmark in this market segment today. Indeed, more than 500,000 customers around the world can vouch for the talents of the GS models and their incomparable boxer engine.

How Was the G/S Created?

How Was the G/S Created?

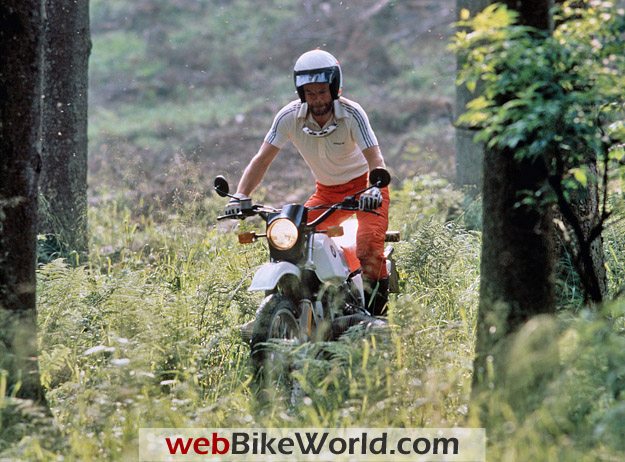

The history of the GS models is actually grounded not so much in dramatic long-distance treks as in the energetic weekend entertainment enjoyed by two engineers and an off-road enthusiast from the BMW Motorrad testing department.

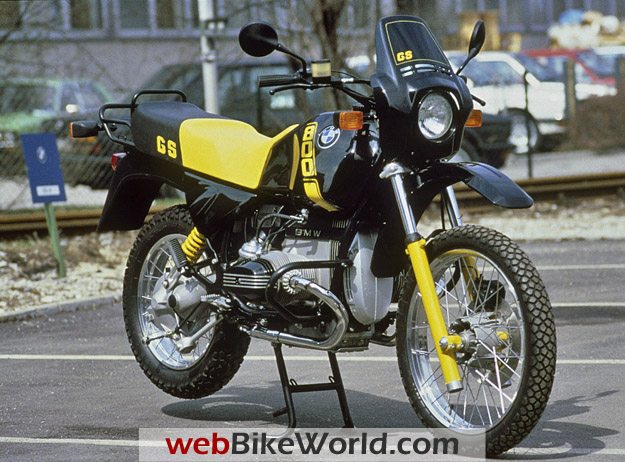

The early R 80 G/S can claim to have several different parents. The role of icebreaker was played by BMW motorcycle testing engineer Laszlo Peres and his GS 800, which emerged from the BMW testing department in late 1977 to lay the groundwork for the later G/S models.

Alongside Peres’ purpose-built 800 cc sports machine, the motorcycle testing department had built privately ordered, close-to-series enduro conversions. These models showed that the boxer concept possessed off-road capability not shared by other large-capacity rivals. Indeed, even the /5, /6 and /7 models designed from the mid-1960s could claim a certain degree of off-road aptitude.

Early prototype trials had been taking place since 1964 as part of the German Off-road Championship. But come the 1970s, requests from customers had prompted the BMW developers to tailor the new model series more towards high-speed road use.

On January 1, 1979 a new management team took over in the corridors of power at BMW Motorrad GmbH. Their priority was to get the motorcycle business – which had been on the wane since the previous year – moving in the right direction again.

The BMW G/S was launched in model year 1979 against a background of falling sales following nearly a decade of growth. The causes of the downturn were identified as the weak dollar, which was hindering performance in the main export market of the USA in particular, and an excessively conservative model strategy. Given its relatively small unit figures – BMW Motorrad GmbH’s sales at the time were a third of today’s levels – BMW decided to retain its tried-and-tested modular system rather than develop a special drive unit for each model. The company’s Japanese competitors took a different line, pursuing what could almost be described as an inflationary model policy.

Karl Heinz Gerlinger, then head of sales and marketing at BMW Motorrad GmbH, looks back at that period:

“First you have to take yourself back to the situation at the time. The competition from the Far East was overwhelming. The Japanese manufacturers were the dominant force in world markets, both where motorcycles provided purely a mode of transport and where they were already being used for leisure purposes. “HOKASUYA Inc.” was the king of the market.

The Japanese brands offered something for every taste, at every price level, and occupied every conceivable market niche. New products were rolled out in rapid succession, and the resultant sale of old stocks led to an extreme drop-off in prices. The motorcycle market was booming, but BMW could only look on from the sidelines as sales tumbled. For BMW dealers, it was like being left off the guest list for the biggest party in town; they were demoralized. BMW Motorrad was in danger of becoming a ‘nostalgia brand’.”

With its boxer models perceived as conservative, BMW was under massive pressure from its competitors. A t this point, the three and four-cylinder K-Series machines with their state-of-the-art engine technology were still three to four years away, the far-reaching project to develop a totally new model series having been launched just a few months earlier.

The obvious course of action for the BMW product planners was therefore to highlight the virtues of the proven boxer engine to new customers and strengthen its popularity for a seventh decade, as Karl Heinz Gerlinger recalls:

“Part of the solution cam from within the walls of the development department, where a BMW enduro quietly took shape. A boxer with a single-sided swing arm – what a wonderful new creation! However, the sense of excitement was tempered by a host of questions. Can boxers really ‘fly’? Is it possible to present such a large motorcycle to customers – credibly – as an enduro?”

Can Boxers Fly?

Can Boxers Fly?

The answer to this question was to be found in the sporting arena. In 1978 the German motor sport authorities introduced an over-750 cc class of off-road competition for the first time.

Backed by the head of motorcycle testing, Peres – an experienced off-road rider – teamed up with two employees to create a registration-approved off-road machine powered by an 800 cc boxer engine and weighing just 124 kg. Peres rode the machine to the runners-up spot in the German championship, showcasing BMW’s off-road potential.

The brand went one better the following year, claiming the championship title in the large-capacity class with rider Richard Schalber. The BMW factory team delivered another show of strength in the International Six Days Trial in Siegerland, West Germany, in 1979; Fritz Witzel Junior and Rolf Witthöft won a brace of gold medals in a competition attracting significant public interest.

The Six Days Trial was very much the Olympics of off-road motorcycling at the time, a gold medal reflecting elite performance in terms of both riding ability and bike technology. BMW had made the breakthrough.

The valuable knowledge the brand built up through its highly publicized involvement in sporting competition was channeled into the development of the new enduro. It wasn’t only the endeavors of the competing machines that was so valuable here; the experience gained with the support bikes – based on the R 80/7 – also played an important role. These motorcycles had to be able to follow the competition machines wherever they went and yet remain as close as possible to a series production blueprint.

Serial Winners

The BMW testing department condensed all this knowledge into the new bike presented to the international press in Avignon, France on 1 September 1980.

The concept of a touring motorcycle with off-road ability was a new phenomenon in the global motorcycle industry, as was single-sided suspension on a large-capacity machine. Together, they caused a genuine sensation.

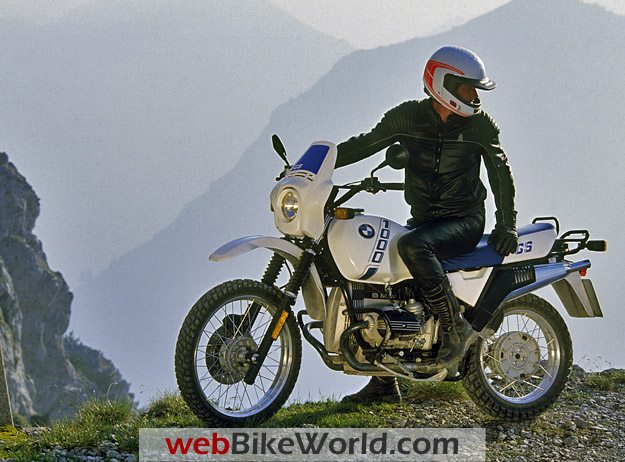

Skeptics had wondered aloud how an 800 cc model with a shaft drive and weighing 200 kg could be even vaguely suited to off-road riding, but a press event for the new machine left the attendant journalists vociferous in their praise – “The best road motorcycle BMW has ever built,” summed up German biking magazine Motorrad.

On the road, the 800 cc model producing 50 hp ticked every box, while off the beaten track it proved more usable than the prophets of doom had predicted. The critics who, ahead of the presentation, had dismissed the new BMW as a poor compromise quickly fell silent as the new arrival proceeded to establish a whole new class of motorcycle.

BMW promoted the versatility of the R 80 G/S with this phrase: “Sports machine, touring machine, enduro… Welcome to a motorcycle concept with more than one string to its bow.”

This summed up the appeal of what was a stylistically fresh and innovative machine with unrivalled all-round capability. With no dramatic loss of ride comfort or on-road performance, BMW had created a motorcycle which could easily hold its own on any kind of road – or mountain track. Its scope of usage comfortably surpassed that of any other all-rounder that had gone before, and was complemented by both the ease of maintenance that had become typical of the BMW brand and an image that exuded reliability.

The R 80 G/S weighed some 30 kilograms less than the R 80/7 road model. This weight saving promised to be a recipe for stand-out handling characteristics, and lent the machine a visual lightness.

Cutting-Edge Technology With Timeless Style

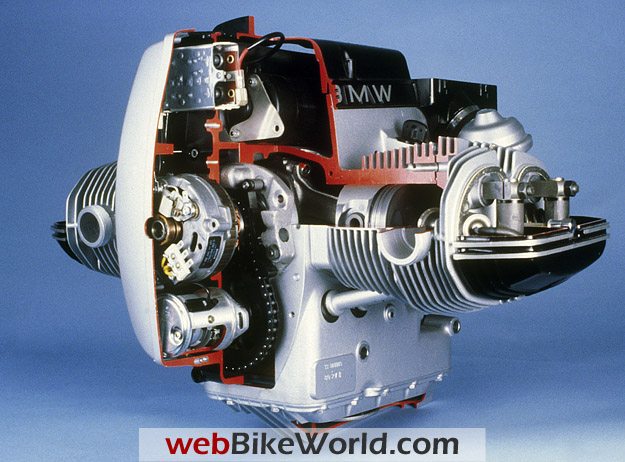

However, it was the single-sided swing arm – hotly debated among BMW fans and beyond – that remained the most talked-about feature of the new machine.

Christened the “Monolever”, this suspension system had no swing arm or spring strut on the left-hand side, as the concept did not feature an axle as such. The wheel hub was fixed to the crown wheel housing of the rear drive with three bolts, like on a car. Whichever way you looked at it, this was a step forward.

This configuration was two kilos lighter than a conventional solution, and the swing arm had greater torsional rigidity, was cheaper to manufacture and made maintenance and repairs that much easier. Plus, there was nothing on the left-hand side of the bike to obstruct the compact installation of the two-into-one exhaust system.

Aside from the pivot point of the spring strut on the upper right loop, some small brackets and the positioning of the footrests, the frame was identical to the main frame of the R 45 and R 65 models. The proven OHV engine had been revised well beyond the scope of its scheduled update, setting it up for another decade and more of service.

Strengthened engine housing with improved lubrication guaranteed greater thermal stability and a longer service life. The sump, meanwhile, was protected by a perforated plate. Elsewhere, the lighter-weight cylinders with coated contact surfaces sliced 3.4 kg off the bike’s weight, while the new 40-per-cent-lighter clutch on the G/S saved a remarkable 4.7 kg.

This clutch, which also served as a flywheel, enhanced the smoothness of the 5-speed transmission and increased the engine’s agility.

Also making its debut on a BMW was the maintenance-free, contact-free electronic ignition system from Bosch, which likewise saved weight and occupied less space with its twin ignition coil. Plus, the new low-profile air filter allowed easier assembly and reduced intake noise. All the modifications helped to ensure that the G/S engine was lighter, more agile and durable than its predecessors.

The clearly arranged central electrics were also sourced from the R 45 and R 65. The twin ignition coil and all relays were located under a 19.5-liter fuel tank – with familiar enduro screw cap – which had been specially designed for the G/S.

The fork and brake disc were taken from the R 100/7. Never before had there been an enduro bike with a disc brake. And never before had an enduro reached 168 km/h in type approval testing, the engine drumming up 50 hp from its 798 cc displacement at 6,500 rpm.

New plastic parts, such as the cover for the H-4 headlamp (used for the first time on an enduro bike), the front fender fixed to the lower fork bridge, the side cover, the seat bench with lightweight and corrosion-resistant plastic base and the functionally designed rear fender, rounded off the lithe appearance of the R 80 G/S.

Up to that point, motorcycles equipped for off-road use were not up to speeds of more than 140 km/h and never weighed more than 150 kg. The G/S also broke new ground when it came to its tires; their off-road tread now had to withstand a top speed of 180 km/h. With this wide range of modifications, the R 80 G/S represented the most fundamental revision yet of the BMW motorcycle technology introduced in 1969.

Boldness Gets Rewarded

The excitement at the IFMA stand was reflected not only in the large number of spontaneous orders taken at the show, but also in sustained customer interest.

By the end of 1981, a total of 6,631 motorcycles – more than twice the number originally planned – had left the halls of the Berlin plant; one in five BMWs sold in 1981 was a G/S. The company’s boldness was rewarded with the establishment of a new market segment – the touring enduro – playing a critical role in reviving BMW’s sales figures. Indeed, this market segment remains hugely important for BMW today.

Out of nowhere, the R 80 G/S became the model of choice for the adventurous at heart and fans of long-distance treks.

One such rider was Hans Tholstrup, born in Denmark but resident in Australia since 1965. Having already completed the fastest motorcycle circuit around the world in 1974 – also on a BMW – Tholstrup undertook a similar expedition with an R 80 G/S in 1981. This made him one of the first motorcycle globetrotters to place their trust in the G/S for such epic journeys.

Anyone for Desert?

At the same time, BMW was stepping up its involvement in off-road sporting competition. Next up on the radar after the European competitions was the world’s toughest and most publicized off-road event: the Paris-Dakar Rally.

First held in 1979, the Paris-Dakar route covered 9,500 kilometers, just 30 per cent of which was over surfaced roads. In 1980 Jean-Claude Morellet – better known by his pseudonym “Fenouil” – finished in fifth place on a BMW.

The brand returned to the race in 1981 with increased vigor. This time the factory machines were prepared by HPN, based in Seibersdorf in Bavaria, in close cooperation with BMW Motorsport.

This small specialist firm called on its deep well of endurance racing expertise in creating the technical basis for the R 80 G/S, which Hubert Auriol rode to a stunning victory in the rally. Auriol finished three hours ahead of his nearest challenger, while “Fenouil” came home fourth.

A privately-entered BMW ridden by French policeman Bernard Neimer crossed the finish line seventh, highlighting the potential of a series-production BMW motorcycle showing only minimal modifications. The market picked up on BMW’s success in the Dakar and sales figures for the G/S rose around the world.

BMW chalked up overall victory once again in 1983. With experienced BMW tuner and off-road rider Herbert Scheck having boosted engine capacity to 980 cc and output to 70 hp, Hubert Auriol stormed to a second Dakar triumph on his factory BMW. The Frenchman then followed up this success by winning the Baja California race.

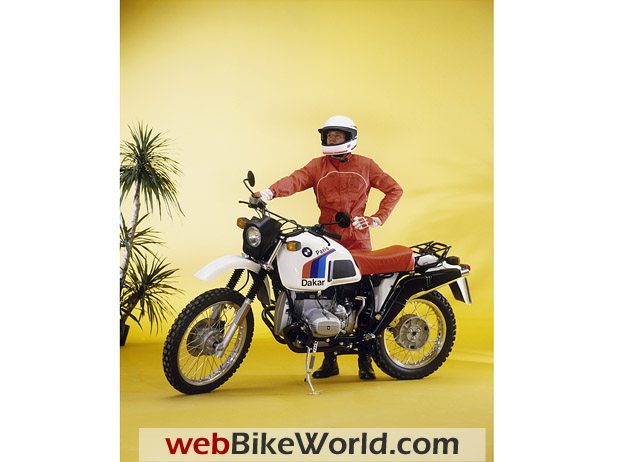

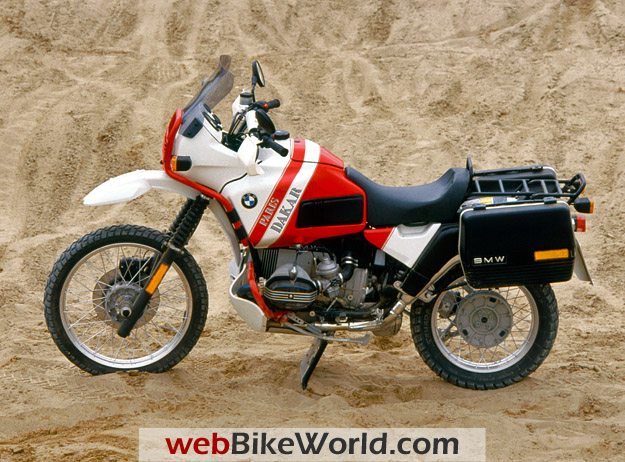

Victory in the 1984 Dakar went to BMW’s Belgian rider Gaston Rahier. Slight in stature but a fearsome competitor, the professional motocross specialist steered his factory machine across the finish line ahead of Auriol on the second BMW. The brand’s one-two inspired a desirable special-edition R 80 G/S bearing the Dakar name.

The R 80 G/S “Paris-Dakar”

The “Paris-Dakar” version of the GS was released for general sale, its 32-liter fuel tank and a comfortable single seat with luggage rack (in place of the double seat) setting it apart from the standard G/S. The “Dakar” – as it soon became known – was delivered from the factory with a combination of protective bars and side stands, which made good sense for anyone contemplating hard enduro riding. Standard Michelin rough-tread tires set the seal on the package.

The Paris-Dakar components were also available individually or as a kit. Almost 3,000 customers – in addition to the kit buyers – chose the 800 cc Dakar over the standard R 80 G/S.

With the first examples of the R 80 G/S “Paris-Dakar” delivered to customers in late 1984, it was fitting that Rahier should be the first rider into the Senegalese capital once again in 1985, giving BMW its fourth Dakar victory in five years. This remarkable record of success put to bed those early concerns as to whether the company could make a credible case for a boxer BMW as an enduro machine.

Impressive evidence of the boxer BMW’s off-road potential came not only in the form of those four victories in the Dakar; there was also success to report on the American continent.

Baja California – the 1,200-kilometre-long peninsula on the southern tip of North America’s west coast – had hosted a legendary desert race for motorcycles since 1975. It was an event characterized by long stages and big variations in terrain. BMW riders Gaston Rahier and Eddy Hau celebrated victory in the large-capacity class in both 1984 and 1985, vividly highlighting the G/S’s rugged talents to North American customers.

The BMW R 80 G/S was also a big success for BMW on the balance sheet, the company delivering 21,864 units to customers by July 1987.

The R 80 GS / R 100 GS

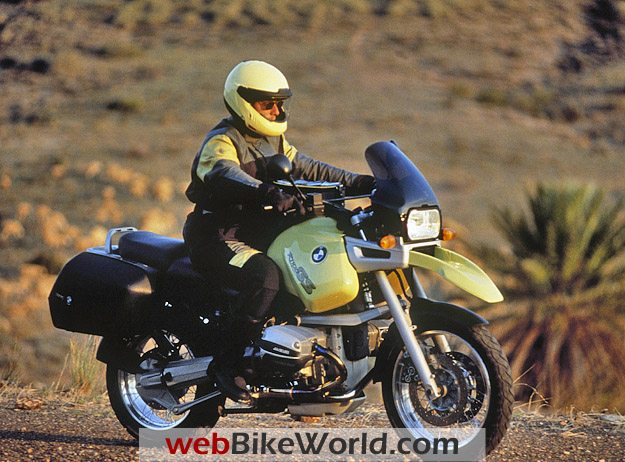

Success remained a constant companion of BMW as the company set about addressing a host of customer requests with the next model off the line. The result was presented in late summer 1987 in the form of the R 80 GS / R 100 GS duo, which promised greater comfort, improved performance and better brakes.

The engine on the R 100 GS was familiar from the previous year’s R 100 RS, and its brawny characteristics made it an excellent match for the touring enduro.

The existing variant with output of 50 hp from 798 cc displacement at 6,500 rpm was now joined by a unit delivering a full 60 hp from 980 cc at 6,500 rpm. However, much more significant than the larger displacement were the enhanced handling and comfort of the new models.

A new rear-wheel swing arm construction, christened the “BMW Paralever”, largely eliminated the negative side effects of the shaft drive system, whereby the rear would lift under acceleration as the suspension stiffened up. Engineers had known about this “shaft effect” phenomenon, which was a particular problem under heavy acceleration on poor surfaces, for decades. Indeed, BMW engineer Alex von Falkenhausen had fitted the BMW factory racing machines with a double-joint swing arm as early as 1955 in order to improve handling.

However, this technology – for which BMW secured a patent – was not initially carried over to series production and BMW motorcycles retained the standard rear swing arm with universal joint until 1987. The trick of using a parallelogram-type suspension system to decouple the rear-wheel swing arm from drive and deceleration forces meant this “shaft effect” was almost entirely absent on the new BMW models.

BMW was keen to make good use of this stand-out technical feature. Indeed, with a sound set of test results under their belt they soon decided to adopt the Paralever single-sided swing arm for the successor to the R 80 G/S, the R 80 GS.

Innovations could also be found in the front wheel location of the GS. In order to introduce travel-dependent damping – a new technical development at the time – into the much stronger fork, a conventional construction in the left-hand strut was combined with a conical bushing working in conjunction with a valve in the right-hand unit.

As a consequence, the compression stage in the fork through the first stage of suspension travel barely had any effect. The result was outstanding ride comfort; however, when the fork compressed, the cone caused the annular gap to shrink, stiffening up the damping and ensuring that the fork could even withstand landings after jumps.

Added to which, the fork now suffered barely any contortion thanks to the installation of a hollow, and therefore lightweight, 25-mm-diameter axle.

But the innovations on the R 80 GS / R 100 GS did not end with the swing arm and telescopic fork. The construction of the new cross-spoke wheels also represented a world premiere. These wire-spoked wheels also allowed the use of tubeless tires, and individual spokes could be replaced without having to take off the wheel or tire.

However, the most important achievement concerned the flat spoke angle, which enhanced elasticity and gave the wheels incredible robustness against impacts and overloading. And there was also more space available for the upsized brake callipers of the larger brake discs.

Both the individual chassis components and the chassis as a whole were newly thought-out and developed, as was the frame. The cross tubes above and below the likewise revised swing arm mounting were stronger than those of the R 80 G/S. And the pivot point of the right rear spring strut on the main frame had also been modified. The only brand new element was the stiffer, longer and heavier rear subframe, which was bolted to the main frame, as before.

In response to requests from a large number of customers, BMW also upped the capacity of the fuel tank to 26 liters. The new tank offered a good compromise between the predecessor model’s standard 19.5 liters and the Dakar version, which could hold a seldom required 32 liters.

A larger and more comfortable seat bench was a longstanding fixture of many customers’ wish lists, and refinements were also made to a range of smaller details.

The new, longer rear subframe allowed the engineers to fit a more powerful battery. Four wheel bolts ensured the rear wheel was safely secured, hinged clamps instead of screw clamps held the bellows to the fork, and the large tank cap was now lockable and made it easier to refuel from a can, as you often need to when riding off-road.

A large light-alloy plate in front of the centre stand with wide floor rest protected not only the sump, but also the machine’s exhaust manifold.

More than a third of the extra 15 kg in weight carried by the BMW R 80 GS over its predecessor, the R 80 G/S, could be attributed to the larger fuel tank capacity.

The remaining ten kilos were accounted for by the improvements mentioned above, and thus represented a sound investment of weight. The windshield and standard-fitted protection bars with attached oil cooler of the R 100 GS marked it out from the lower-priced 800 cc model.

Press and customers alike were won over by the new model, and sales even trumped those of the R 80 G/S. In Germany the BMW R 100 GS shot straight to the top of the new bike registration lists. The 1,000 cc version was by far the more popular model, despite its higher price tag, fully vindicating BMW’s decision to increase engine output.

The “27 hp” GS: Welcome to the R 65 GS

BMW had also been keeping an eye on the interests of novice motorcycle riders in West Germany who, starting on April 1, 1986, were not permitted to ride models producing more than 27 hp.

In December 1987 the R 65 GS duly went on sale – exclusively in the German market – with the 27 hp engine from the BMW R 65 fitted to the chassis underpinning the BMW R 80 G/S.

BMW was keen to set the new machine apart from the new mid-range R 80 GS enduro and there was also a realization that new riders might be slightly out of their depth with the heavier R 80 GS on a day-to-day basis – something that wouldn’t be an issue with the comparatively light and dainty R 65 GS.

Sales reached 1,727 units, which fell short of the figures normally recorded by 800 cc models. And yet the 146 km/h R 65 GS was very much a typical BMW GS: capable, strong and comfortable. The 650 cc engine, which was 56 mm slimmer than the 800 cc engine, did wonders for handling. Visually, the only difference from the R 80 G/S came in the decoration on the fuel tank.

The smallest GS avoided criticism in the press, but was lost in the shadows of its new, larger siblings, which had arrived to such tumultuous acclaim. Production came to an end in 1991, and the R 65 GS was duly replaced by a 27 hp variant of the R 80 GS.

The Popular “Ship of the Desert”: The R 100 GS Paris-Dakar

Much more successful was a spin-off variant of the R 100 GS. Similarly to the R 80 G/S Paris-Dakar, the R 100 GS Paris-Dakar was born out of a desire to offer a fully-fledged touring motorcycle for the most remote roads on the planet.

A few months earlier, Eddy Hau had imbued the project with a handy portion of sporting credibility by winning the Marathon class at the Paris-Dakar Rally on an HPN-modified production G/S. Hau was the leading independent rider in the race.

Initially only a conversion kit went on sale, but it was followed in March 1989 by the complete machine. The kit included a 35-liter fuel tank with a lockable compartment on the back, as well as an engine protection plate complete with comfortable single seat. This could be combined with an extra luggage rack in place of the pillion seat.

Fixed to the front of the tank was a slim plastic fairing with a rectangular headlamp and a small windshield. On the inner side of the fairing was an “instrument cluster” containing a speedometer, warning lights, a rev counter and a clock. With BMW having notched up four motorcycle wins in the Paris-Dakar, the notorious desert rally was the best possible ambassador when it came to extolling the virtues of the super-durable touring model.

Privateers Celebrate Success With the GS

BMW decided to wind down its works involvement in the Dakar from late 1986, so it was left to privateers Eddy Hau, Richard Schalber and Jutta Kleinschmidt to provide the fireworks which would illuminate the GS Boxer’s sporting talent.

Particularly worthy of note were Hau’s victory on a privately-entered HPN GS in the Marathon class of the 1988 Dakar and Jutta Kleinschmidt’s fifth place in the Marathon section of the 1992 Paris-Cape Town Rally. An engineer at BMW at the time, Kleinschmidt reeled off over 12,700 kilometers to cross the finishing line on what was – with the exception of the spring elements and exhaust system – a standard-issue R 100 GS Paris-Dakar.

Her successful voyage over exacting terrain proved to be the perfect advertisement for the rugged qualities of the boxer model. The impressive and comfortable 1,000 cc machine quickly became a popular favorite and remained in the model range until 1995.

Improved Touring Comfort for the GS

Improved Touring Comfort for the GS

The touring comfort of the Paris-Dakar model was welcomed by customers and the majority of GS buyers did most of their riding on asphalted roads. It was therefore no surprise that the extensive update package introduced for the model year 1991 R 80 GS and R 100 GS reflected these preferences.

The simple windshield on the R 100 GS – available for the 800 cc as a cost option only – disappeared along with the small round headlamp. They were replaced on the GS models by a semi-fairing mounted firmly to the frame. This included a rectangular headlamp which was similar to the one on the R 100 GS Paris-Dakar but adapted to accommodate the 26-liter GS fuel tank.

As on the Paris-Dakar model, protective bars were once again fixed to the frame tubes. Another new feature promptly carried over to the Dakar was the cockpit with two 100 mm circular instruments.

The enduro filler cap gave way to a screw cap with hinged lid and lock. All models were fitted with an improved seat bench and different handlebar switches.

The switches used up to that point were replaced by the handlebar controls from the K models, which also worked excellently when the rider was wearing thick gloves. The rear spring strut was replaced by a higher-quality component with an adjustable damper rebound stage.

Like all other boxer models, the GS models could also be specified – as a cost option – with the pollutant-reducing secondary air system. This technology, which was already tried and tested in the USA and worked according to the principle of exhaust afterburning, cut carbon monoxide emissions by 40 per cent and hydrocarbon emissions by 30 per cent.

As these upgrades were hinting, the old boxer engine was reaching the limits of its design and the BMW Motorrad range was due for another revision. After all, sales of the R 80 GS / R 100 GS models had reached over 45,000 by 1996, confirming the importance of the boxer enduro in the BMW range.

Giant Strides: The R 1100 GS

13 years after the world’s first touring enduro was launched, new environmental regulations, advances in production technology and evolved customer demands meant it was time for the tried-and-trusted two-valve models to make way for a new generation.

January 1993 saw the arrival of the first four-valve boxer engines in the R 1100 RS, with the R 1100 GS following close behind in September of the same year. Its striking styling and clean, functional lines were an instant hit, and were backed up by the some sensational engineering that had already impressed and astonished the motorcycle world in the R 1100 RS.

BMW Motorrad had reviewed the bikes from top to bottom and made sweeping changes. The resulting machine not only provided the basis for what is still an excellent motorcycle concept but also set new standards in sustainability. This was the first enduro that could be specified with a factory-fitted closed-loop catalytic converter and anti-lock braking system.

All the plastic components were labeled for easy recycling, the exhaust system was now made entirely of stainless steel and therefore was no longer a “consumable” item, and service intervals were increased to 10,000 km, previously unheard of for an enduro.

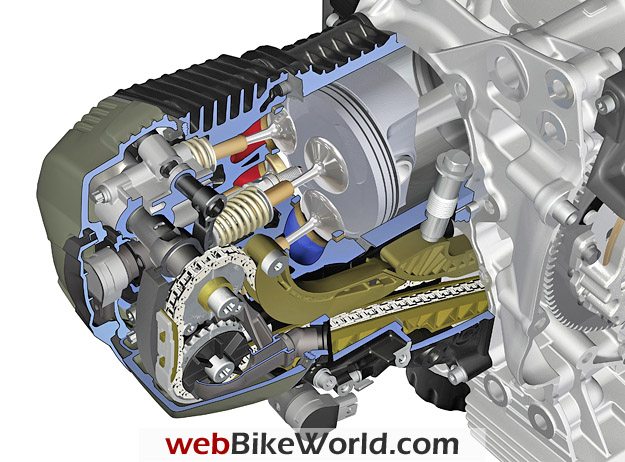

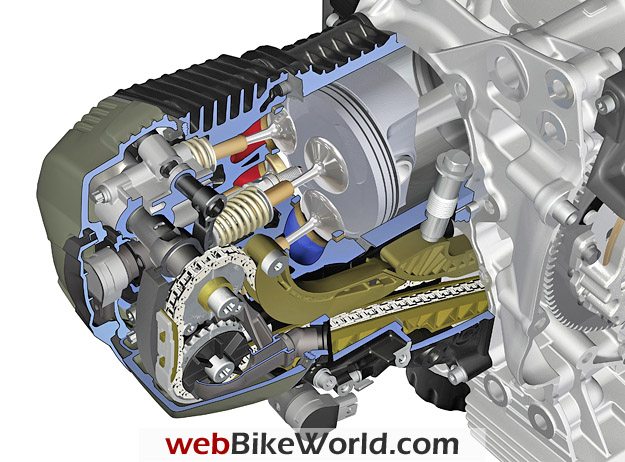

The proven and unique principle of the air-cooled boxer engine with a driveshaft rotating inside the Paralever swing arm was retained unchanged.

The new four-valve engine featured side camshafts, mounted at valve height, which were driven by three timing chains and one intermediate gear. This unusual camshaft positioning was intended to reduce width compared with an OHC valvetrain, and also to ensure rpm stability.

Electronic engine management, fuel injection, an increase in displacement to 1,085 cc and an increased gas flow rate produced 80 hp at 6,750 rpm, an increase over the previous two-valve models. At the same time emissions, noise and specific fuel consumption were reduced.

The new GS model’s driveline was modeled on that of the R 100 GS, and it inherited the tried-and-trusted cross-spoke wheels as well.

The chassis, on the other hand, was an all-new development. The engine and transmission formed a load-bearing unit. Bolted in place above them was the steel tube rear subframe, which provided support for the spring strut in the rear swing arm. The spring strut was continuously adjustable by hand for spring preload and rebound damping.

The front wheel was located by a revolutionary front wheel suspension system, the “Telelever”, which was a combination of a swing arm and a telescopic fork.

Although BMW Motorrad had already pioneered the hydraulically damped telescopic fork, with the Telelever it went one better. The telefork-style combination of fixed and sliding tubes simply serves to locate the front wheel, allowing it to respond quickly to bumps.

The actual suspension and damping is provided by a central strut in front of the steering head. This strut is supported at the top by the cast front frame section and at the bottom by an A-arm. The front end of this suspension arm is mounted by a ball joint in the lower fork brace of the telescopic fork-type wheel locating system.

The upper fork brace accommodates the handlebars, with instruments, and the fixed tubes. It is mounted in the steering head.

Separating the wheel location from the suspension function gives extremely comfortable, yet also precise, handling and steering characteristics. At the same time, the suspension geometry is designed in such a way as to reduce the brake dive that would normally be expected on a bike with soft suspension and long spring travel.

Fitted with a dual-disc brake at the front and single-disc brake at the rear, the R 1100 GS was also the first enduro to be offered with optional anti-lock braking system, which could be disengaged for off-road riding.

Impressive performance, with a top speed of 195 km/h, and torque were mated to superb ride comfort and handling. There were also neat features like the height-adjustable seat, a windshield adjustable for rake and the removable pillion seat which lifted off to give access to a luggage carrier.

The double front mudguard became a cult feature and customers were soon flocking to buy the new GS. By the Spring of 1994 it had become the top favorite among BMW customers.

One customer who didn’t have to put his hand in his pocket, however, was globetrotting adventurer Helge Pedersen. Pedersen had been one of the very first R 80 G/S customers and had now, along with his 800 cc bike that he nicknamed “Olga”, become something of a legend.

The Norwegian photographer had bought his BMW R 80 G/S new in 1981, and before embarking on a world tour had equipped it with a 40-liter fuel tank with attached luggage system. That tour, now completed, had taken ten years, in the course of which he covered 350,000 kilometers.

The R 80 G/S didn’t disappoint, and Pedersen’s travelogues, pictures and books showed just how robustly the G/S had coped with all the challenges along the way. In 1994, Pedersen donated his faithful R 80 G/S to the BMW Museum, and in exchange was allowed to pick up a brand-new R 1100 GS.

New BMW Single-Cylinder: The F 650

More powerful, larger and heavier than its predecessor, the BMW R 1100 GS could be slightly intimidating for entry-level customers. But the expanding BMW model range now offered alternatives.

Since autumn 1993, customers for whom the 1100 models were too powerful and too large could opt for the F 650. Powered by a 650 cc single-cylinder engine developed in close cooperation with Rotax the F 650, built at Aprilia, was soon dubbed the “Funduro”.

Developing a healthy 50 hp from its 650 cc liquid-cooled, four-valve single-cylinder engine, the new BMW outshone established competitor models that were still making do with less advanced engines.

Initially, traditionalists and purists complained that a “real” BMW had to have a boxer engine and shaft drive, but the F 650 quickly made its mark. BMW expressly dubbed it a “Funduro”, rather than an “enduro”, to emphasize that the F was an all-rounder that was fun to ride both on and off the road.

It was cheap, easy to handle, and amazingly fuel-efficient. It also offered a level of comfort previously unheard of for a single-cylinder model. Customers who sampled this new offering were impressed, and the F 650 was soon selling so well that this model, which has been continuously improved on and refined over the years, is still part of the BMW range today.

A Legend Comes Full Circle: The R 80 GS “Basic”

In 1996, traditionalists and purists were treated to one last two-valve GS model, which drew on components from throughout the model range to allow the “old” boxer to end its career on a high note.

This production run came to an end – along with the two-valve boxer era at BMW – in 1997, by which time 3,003 “Basic” models had been produced.

The no-frills, off-road-capable R 80 GS “Basic” brought the two-valve GS models full circle, following closely in the tradition of the very first two-valve prototype, from which the R 75/5 production model was then derived. That prototype too was a sporty off-road/street enduro.

The R 80 G/S was responsible for a boxer renaissance in the early 1980s, and it was with this model that BMW Motorrad launched its touring enduro segment. Now, finally, the two-valve boxer engines bowed out and passed on the baton to the four-valve models, which went on to become an even bigger success than their predecessors.

In 1998, BMW celebrated 75 years of motorcycle production, marking the occasion with a lavishly equipped anniversary edition of the R 1100 GS.

The “Better” R 1100 GS: The R 1150 GS

But while good is good, better is better. By 1998, engineers were already busy testing the R 1150 GS, ready for its market debut the very next year.

Before that, however, a smaller-displacement GS was launched, whose 848 cc engine, taken from the entry-level R 850 R Boxer model, developed 70 hp at 7,000 rpm. But this refined four-valve enduro fell far short of the 1100’s sales figures.

In fact, the whole episode turned into a rerun of the experiences with the R 65 GS and R 80 GS. Only 1,954 R 850 GS models were sold, as against 43,628 R 1100 GS models. The lesson was that BMW Boxer customers are fond of high-capacity engines and tend to subscribe to the dictum “no half-measures”.

Launched on the market in September 1999, the R 1150 GS (more) promptly set about becoming even more successful than its predecessor. Not only did this model boast larger displacement than the R 1100 GS, it also used a neat trick to increase output, delivering maximum power of 85 hp, at 6,750 rpm, from a displacement of 1,130 cc.

The cylinders and pistons were taken from the BMW R 1200 C, and the crank assembly and cylinder heads from the BMW R 1100 S. This lavish package was completed by a more compact clutch, the six-speed transmission as used in the R 1100 S and a performance-enhancing exhaust system.

Fresh Ideas: The F 650 GS and F 650 GS Dakar

Customers who didn’t want a full-blown 1100 GS quickly got over the demise of the R 850 GS when new versions of the F 650 – the F 650 (more) and the F 650 GS Dakar – were brought out in spring 2000.

Production was now transferred from Italy to the BMW motorcycle plant in Berlin. At the same time, the BMW engineers had subjected this popular seven-year-old compact model, which had helped to introduce many new motorcyclists to the brand, to sweeping revisions that went well beyond the normal run of updating and modernization measures.

Both bikes retained the same overall concept as the popular F 650, but along with fresh new body styling there were technical improvements as well, which helped to keep the popularity of the single-cylinder models alive and thriving.

The single-loop frame was replaced by a perimeter frame and the twin carburetors were superseded by fuel injection. A three-way catalytic converter was fitted as standard, making this emission control technology now universal on all BMW models.

The fuel tank was now fitted in the frame triangle, lowering the centre of gravity. With its fuel injection system and new tuning, the F 650’s engine again set new standards on fuel consumption, torque and power.

Off-road fans meanwhile were delighted with the all-new F 650 GS Dakar, which boasted longer spring travel, a 21-inch front wheel and a robust windshield. Initially, this bike had simply been intended as a special-edition model, but it sold so well that it remained in the range right up until 2007.

The 650 models were approximately on a par with the R 80 G/S in terms of power and weight, but they offered better ride comfort and fuel consumption. Incidentally, BMW had already returned to long-distance off-road competition in 1998 with the robust single-cylinder 650 models, and had gone on to win the 1999 Paris-Dakar Rally with an F 650 RR.

Four-Valve GS: The R 900 RR

But the fans had a soft spot for boxer models, and in late 1999 a BMW R 1150 GS piloted by Britain’s John Deacon and Californian rider Jimmy Lewis launched its preparations for the 2000 Dakar by contesting the UAE Desert Challenge.

For the Dakar, its displacement was reduced from 1,085 cc to a punchy 900 cc. BMW ended an extremely grueling contest with a sensational one-two-three-four finish in the legendary Africa Rally to mark the start of the new millennium. Lewis came third on the R 900 RR boxer bike, while the other top-four finishers were riding the F 650 RR.

The Globetrotter’s Favorite Ride: The R 1150 GS “Adventure”

The R 1150 GS “Adventure”, which entered BMW showrooms in the 2002 model year, was an ideal machine for globetrotters.

With its longer spring struts with travel-dependent damping, anodized wheels, large windshield, single-piece seat and sturdier oil sump guard, the Adventure was just the job for world traveler looking for an all-terrain long-distance bike with plenty of staying power.

BMW also offered a well-stocked range of accessories, from model-specific equipment like a 30-liter fuel tank and an extra-robust aluminum luggage system to more general, classic BMW accessories like heated grips or the further improved ABS II. There were thoughtful details as well, like a side stand with larger pad for parking the machine on soft ground.

Only a few weeks after the release of the “Adventure” model, all the four-valve bikes went over to twin-spark ignition to meet Euro 3 emissions standards, and to ensure smoother running at low load and rpm.

Worldwide Success for the GS

The big four-valve GS models had already long been the top favorite with German motorcycle customers and their popularity now spread to other European countries as well, particularly Britain and Italy. In the course of its production run, satisfied customers took delivery of 71,137 R 1150 GS models (including Adventure models).

The best-known Adventure pilots were the British duo of Ewan McGregor and Charley Boorman, who made an unescorted round-the-world trip that was also documented in a BBC TV series “Long Way Round“, which attracted large audiences all over the world.

Since the bikes gave an impressive display, demonstrating the staying power of the GS to a large European television audience, GS motorcycles for long-distance touring now became increasingly popular. In the English-speaking world particularly, these models were soon attracting more interest than ever before.

Although the Adventure’s specifications met virtually any and every need of long-distance riders, these amenities also had the effect of increasing the bike’s weight and raising its centre of gravity. So one of the top priorities for the next-generation four-valve models was to shed as much weight as possible.

Next Up: The R 1200 GS

In summer 2004, BMW presented a new generation of its classic enduro model. Rather than facelift the existing R 1150 GS, the company decided to create a new motorcycle, the R 1200 GS (more), which would offer all the advantages of the predecessor models but in a far more dynamic form.

Even more impressive than the further increases in displacement (to 1,170 cc), torque (an amazing 115 Nm at 5,500 rpm) and power (98 hp at 7,000 rpm) were the “belt-tightening” measures: fuel consumption had been cut by 8 per cent and, even more importantly, the BMW R 1200 GS was almost 30 kilograms lighter than its predecessor.

The dry weight of 200 kilograms set new standards for a large touring enduro. Weight was reduced right across the board, with almost every component of the new BMW making its contribution. The swing arm, the frame, the wheels and the cable harness – thanks to CAN data bus technology – all lost weight.

Even the engine was now three kilograms lighter, despite being more powerful, and despite the weighted balance shaft rotating counter to the crankshaft that served to maintain the legendary BMW refinement even with the large cylinder displacement.

The innovations extended to the electronics as well, with a simplified cable harness now transmitting CAN data bus signals, a standard-fitted flat screen display providing information about fuel level, oil temperature, time and other data, and new fully sequential fuel injection with computer-controlled ignition helping to make the BMW R 1200 GS both faster and more fuel-efficient than its predecessors.

A practical feature for long-distance riders was anti-knock control, which altered the spark timing at each of the four spark plugs as and when required. This meant that lower-quality fuel could be used without damaging the engine – which was just the job on trips through areas where filling stations were few and far between.

Also new was the transmission, which featured quiet helical gearing throughout, and the extended maintenance intervals. The new, lightweight rear differential, which was filled for life, and the standard-fitted steel flex brake lines were further good news on the servicing front.

The front frame was of welded steel rather than cast aluminum, for improved robustness – particularly off-road.

The styling, too, had a leaner look, so that the weight loss didn’t just bring improved performance but could also be appreciated when the bike was in repose.

The cross-spoke wheels had now become an option, with lighter cast wheels fitted as standard, while the optional ABS that could be disengaged was a semi-integral version, with a hand lever that braked both the front and the rear wheel, and with a brake booster providing further support.

All these improvements were also featured just over a year later on the BMW R 1200 GS Adventure (more), which now replaced the BMW R 1150 Adventure.

With all this going for it, the R 1200 GS couldn’t fail to be a success, and since 2005 it has been the undisputed number 1 on the German market. The talented all-rounder is also winning more and more friends in markets throughout the world. After just three years, sales of the two large BMW enduros had already topped the 100,000 mark.

The HP2 Enduro – Powerful Boxer for the Down-and-Dirty Work

The HP2 Enduro (more) was the first ever production BMW motorbike with a seat height of 920 mm. But the robustly uncompromising nature of the HP2 Enduro, unveiled in 2005, was all part of its charm. The name alone – HP stands for “high performance” – was an indication that this is very much a sports machine.

For many boxer fans, this was a dream come true. Never before had a boxer model been this light and athletic and had such radical off-road capabilities.

Project manager Markus Theobald had the pleasure of designing the pared down yet highly sophisticated HP2 Enduro. There had already been plans for a radical off-road boxer years before, but not until the relatively lightweight R 1200 GS was a suitable technical basis available for developing such a machine.

The engineers had already gained experience with the tubular space frame from working with the R 900 RR, while for the engine and driveline they were able to draw on the R 1200 GS. The air spring strut and TDD telescopic fork gave the bike competitive speed on the worst imaginable off-road trails.

Here the HP2 Enduro went way beyond all previous GS models. The handling, heavily influenced by the 21-inch front wheel and the light weight of the bike, was unrivalled too. But obviously such an ex-works collector’s machine could neither be cheap nor meet a wide spectrum of wants and needs. The production run was consequently limited to 2005 and 2006.

Long Way Down…And Other GS Adventure Stories

In 2007, the popular McGregor/Boorman team were back in the saddle again. The TV series, DVD and book of this new trip were entitled “Long Way Down“.

The three-month trip and media spectacle saw the pair ride from Scotland through Western Europe to South Africa. Not too surprisingly, the duo once again chose BMW bikes for their 25,000-kilometer journey. This time round they were riding the BMW R 1200 GS Adventure.

Germany’s most famous globetrotting motorcycle adventurer has to be Michael Martin. Since 1992, Munich-born Martin has been using the large BMW GS models for numerous sensational expeditions – for example between 1999 and 2004 he visited all the world’s deserts. Martin has documented his creative, but often physically extreme tours in 15 books and more than 1,000 slide shows.

Helge Pedersen, too, continues to rely on the big BMW GS models for his long-distance journeys. In 2008 he took part in the GlobeRiders Worldtour, making a 16,000-kilometre trip from Beijing to Munich.

While McGregor, Boorman, Pedersen and Martin use state-of-the-art GS models, some world adventurers remain loyal to their long-serving two-valve machines. Austrian triathlete Felix Bergmeister, for example, made a round-the-world trip on a BMW R 80 GS Basic.

And British motorcycle traveller Tiffany Coates has no desire to part with her 18-year-old BMW R 100 GS, on which she has already clocked up 280,000 kilometers in every continent – further proof of the reliability and long life of the large BMW enduro.

Meanwhile, after spending 11 years working in Hong Kong, another loyal devotee, Scotsman Mike McCabe, is now back in the saddle and returning to his native Scotland on his R 1200 GS Adventure.

F Models as Popular as Ever: The F 650 GS / F 800 GS

The GS boxer models are not the only ones to have acquired more powerful engines over the course of time. In 2008, the F 650 GS Funduro, and its sister model the F 650 “Dakar”, were replaced by a new F 800 GS twin-cylinder model (more information | wBW Review). The new models are powered by a parallel twin-cylinder engine taken from the F 800 S and F 800 ST street models, which were launched in 2006.

The F 800 GS enduro is not only equipped with the same engine as the 800-Series street machines but also with the same tubular space frame.

In terms of engine size and weight, this model follows in the tradition of the original GS boxer models. With a 21-inch front wheel, large ground clearance and more than 200 millimeters of spring travel, it can take on any type of terrain, while on the road its agile, 85 hp engine powers it vigorously up to the 200 km/h mark.

However, with the parallel twin-cylinder engine, liquid cooling and chain drive to the rear wheel, this was a completely different technical concept from that of the tried-and-tested boxer models. Not that this worries the customers – who are delighted that BMW is not just confining itself to classic boxer models.

The BMW GS range offers the right concept for any and every need. The particular strengths of the twin-cylinder 800 model, for example, are its compact design, outstanding fuel economy, agile performance and robust design.

In 2008, the company then brought out a new version of the F 650 GS. This nomenclature erred very much on the side of modesty, since the displacement of this model – 798 cc – was the same as that of the F 800 GS.

The only difference was that it was a little more softly tuned than in the F 800 GS version, making it more suitable for less experienced riders or those with a more leisurely riding style.

With 71 hp on tap, the F 650 GS too packs plenty of punch, while a seat height of just 790 mm and a 19-inch front wheel with precisely calibrated steering geometry make for an extremely manageable and maneuverable all-round bike that inspires confidence right from the word go.

The predecessor – the single-cylinder F 650 GS – is still in production in Berlin and Brazil, but only for specific markets.

The GS Just Keeps Getting Better

In 2007, three years after its launch, the BMW R 1200 GS underwent a facelift that introduced a large number of detail improvements.

For example, the large GS bike became a little more agile with the incorporation of the six-speed transmission from the boxer-engined HP2 Sport street bike, with sportier gear ratio spacing.

The GS now shares its pistons and camshaft with the R 1200 R and RT, raising maximum output to 105 hp at 7,500 rpm. Seat comfort, already good, was further improved by somewhat more lavish padding in the front area of the seat. The light-alloy tapered handlebars are more flexible and more comfortable, while newly developed clamps allow better adjustment of the handlebars to the rider’s individual physique under a wide variety of off-road and on-road conditions.

Visually, the revised BMW R 1200 GS can be identified by the striking light-alloy side covers on the fuel tank and by the failsafe LED rear light, features which give this functionally superb machine a certain technoid charm.

A further innovation demonstrating BMW’s commitment to user-friendly engineering is the Enduro ESA system, which has been available since 2008.

ESA (Electronic Suspension Adjustment) allows the rider to adjust the shock absorber spring preload and rebound damping on the fly, via a handlebar control and step motors. This user-friendly innovation allows the suspension components to be adjusted to different road and load conditions, or the personal preferences of rider and passenger.

The Enduro ESA system, adopted from the sport models and further refined, is a perfect example of the GS’s strategy of adapting as closely as possible to every conceivable customer requirement.

Modernized Yet Again: The GS at 30

To mark its 30th birthday, the evergreen GS boxer engine was given a sporty makeover, with the 2010 models inheriting the high-tech cylinder heads of the meteoric HP2 Sport (more), with two overhead camshafts per cylinder.

The new radial valve arrangement resulted in improved rpm stability and volumetric efficiency and a more efficient combustion chamber design.

Since an all-out focus on maximum power would have conflicted with the versatility that continues to be the hallmark of the boxer engine in this latest incarnation, the increase in output, to 110 hp at 7,750 rpm, is relatively moderate. A more important priority was to ensure a further increase in torque over a wide rpm range.

The increased compression ratio allows the GS to achieve outstanding fuel efficiency and, thanks to the extremely advanced combustion chamber design and the anti-knock control for the centrally located spark plugs, there are no problems on long-distance tours through countries with variable fuel quality.

The cams have been designed with a new conical cam profile to take account of the radial valve arrangement. The increased valve diameters and throttle valve housing diameter improve volumetric efficiency.

An air filter with higher air flow rate completes the performance enhancements. For the German market, the 2010 GS model is alternatively available in a derated 98 hp version, which takes into account the German insurance categories.

A modified valve cover ensures that the revised engine can be distinguished from its predecessor even at first glance.

The GS and its sister model, the Adventure, have for many years been not only the most popular BMW motorcycles, but in some countries the bestselling motorcycle per se.

Clearly, the fathers of the original R 80 G/S had the right instinct when they went against the trend towards increasing specialization and opted instead to create an all-rounder with strong touring qualities. In the three decades since the first G/S was presented, the large touring enduros have cornered an impressive market share.

But it would be wrong, when looking back with justifiable pride on all the achievements to date, to succumb to nostalgia or complacency.

“Life can only be lived forwards, not backwards…” according to Mike Carter, who gave up his career in London to learn to ride an R 1200 GS prior to embarking on a round-the-world trip on a 1200 GS Adventure.

The globetrotting journalist’s words are a reminder that continuous evolutionary development is vital if the GS is to retain its character and the position it has consistently held over the past three decades as the benchmark among touring enduros.

Owner Comments and Feedback

See details on submitting comments.

From “D.H.” (May 2015): “Just a quick note to thank you for the excellent article on the GS motorcycle.

I have been a fan of BMWs for a long time, way before they were “cool”. I had the joy of visiting the Berlin factory in the early 90’s and was highly impressed by the skill and dedication of the workforce — I still have my visit brochure!

Regarding the Ewan and Charlie comment about being “unescorted”, I think that it is actually correct to state that they were unescorted.

Whilst they did have a support crew, in London and on the road, this was primarily to support the filming. They were unescorted by BMW. Those guys rode every mile themselves.

I do not know why people choose to criticise them. They have done an excellent job of popularising our chosen past time and deserve credit for this.

As a point to ponder, do we criticise the brave men and women who ride in the Dakar rally (or similar)? No, not even when they are supported by the manufacturers.

Anyway, thanks for the great article. It was interesting and informative.”

From “H.S.” (January 2015): “That was a good article on the BMW GS. As a matter of clarification, it was stated toward the end of the article that Ewan McGregor and Charlie Boorman took an ‘unescorted’ around the world tour on BMW GSs. In fact, they were highly escorted with a rather large support team. They traveled from west to east in late spring of 2004 and wrote a book ‘Long Way Round’.

On the other hand, my riding partner Dennis O’Neil and I traveled roughly the same route, at the same time, from east to west on BMW R1150GSs. We were ‘unescorted’ with virtually no support team. That can be verified in my book ‘Lucille and The XXX Road‘.

I can tell from my book, and their documentary, that we crossed at, or near, Chita, Russia. They were told at that time that they would need to put their bikes on the train to get across the mammoth swamp ahead of them – and they did that. In fact, Dennis and I had just completed that section, the Amur, on our bikes, without using the train. The locals told us we were the first to cross that section. It was a very rugged ride. Thanks for the article.”

Editor’s Note: I should have caught that; the info about Boorman and McGregor’s trip came directly from BMW Motorrad!

From “C.L.” (4/10): “What an excellent article, with some great pictures!

I bought an R80 G/S just like the one in the top photo in 1981 to ride down to Cape Town. Long story short, I got married instead and with HUGE regret, had to sell the bike in ’85.

I am an industrial designer and I can’t tell you how impressed I was with that ‘monolever’ – what superb minimalist elegant design.

In my view BMW lost its way after that model with each successive model getting bigger, and heavier, and more powerful, and more complicated (OK, the 1200 shed a few kgs, but it’s still a monster). The beauty of the 80 G/S was its utter simplicity – it didn’t need more power for its purpose, and every additional kg was to its detriment. And as for the styling – that ugly ‘beak’ has to be one of the most nonsensical, useless styling features on any motorbike!

When I decided recently that it was time to return to biking, I supposed that motorcycling technology would have advanced by leaps and bounds in my absence – I am extremely disappointed to see how little has changed. And what an earth can BMW have been thinking about when it reverted to the loathsome chain on the F80GS?!

I have bought a ’98 R850R to get back into it, and then will have to look around. I might just seek out a good, or restored R80 G/S!”

From “T.C.” (4/10): “In a motorcycle context “enduro” is North American English, despite the root in the Latin word for “hard”. And the reason it had to be combined with another word is that Yamaha claimed the trademark on “Enduro”, that being the name of their pioneering dual-sport DT-1 of 1968.”

Editor’s Reply: Interesting – can anyone confirm the first use of the word “enduro”? I couldn’t find a Yamaha trademark for the word. Unfortunately for Yamaha, they apparently did not keep tight control over the use of the word and it has now gone so far into general use that a trademark would be invalid.

How Was the G/S Created?

How Was the G/S Created? Can Boxers Fly?

Can Boxers Fly?

Improved Touring Comfort for the GS

Improved Touring Comfort for the GS