I feel a bit self-conscious as I park my Toyota Corolla in the yard outside Grant Vlahovic’s workshop. I’d originally planned to ride my bike (a Kawasaki Vulcan 900 Classic LT) out to meet him here in Langley, about an hour east of Vancouver, but the roads have been icy all weekend and I don’t want to risk a spill.

Still, even with Christmas just around the corner (at the time of this interview), many motorcyclists continue riding here in British Columbia’s Lower Mainland, where conditions are considered mild—for Canada, anyway. I’m reminded of this fact and make a mental note to stock up on winter riding gear as Grant steps outside to greet me, wearing a heated vest and Gore-Tex jacket.

The Canadian-born Mr. Vlahovic is a man of many talents. At 60 years old, he’s been a preacher, a teacher, and an opera singer (among other things). But our conversation today will focus on the intersection between his life in motorcycles and his life in Vancouver’s bustling film & television industry, sometimes referred to as Hollywood North by the cast, crew, and other creatives who work here.

Photo via Ashley Ross.

A Man of Many Talents (On & Off-Screen)

Grant and I are both actors, as well as motorcycle enthusiasts—although there’s really no comparison beyond those basic facts. He’s a lifelong rider, red-seal mechanic, flat-track racer, and custom bike builder who’s established himself as the go-to motorcycle supplier for the area’s many production companies. He’s also one of the leads in Long Lost Christmas, a new Hallmark movie that premiered in the US on November 19th.

Meanwhile, I’m a 32-year-old freelance powersports journalist and still-relatively-new rider with one or two modest TV roles under my belt, and I still feel accomplished when I can adjust my clutch cable unassisted. We are not the same.

This is something Grant picks up on right away—it’s obvious from the moment we start talking that I don’t have his highly developed wrenching skills or decades of riding experience—and yet, any initial worries I have about being judged harshly by him are immediately put to rest. “This isn’t my world anymore; it’s yours,” he says. “The more people who can get out and enjoy this way of life, the happier I am—that’s the important thing.”

You might expect someone who’s put so much time and effort into their passion to have stronger opinions, but refreshingly, Grant’s no gatekeeper. He exudes a natural, down-to-earth confidence that never once comes across as smug or superior; he’s open, approachable, and friendly for the duration of our interview.

Photo via Ashley Ross.

It’s easy to see why casting directors want to put him in feel-good holiday movies, despite a shaved head and piercing blue eyes that wouldn’t be out of place on Mayans M.C. or The Devil’s Ride. It’s also easy to see how passionate he is about his work—in motorcycles and in movies. This becomes even more obvious when Grant walks me over to the shed to show me some of his favorite builds.

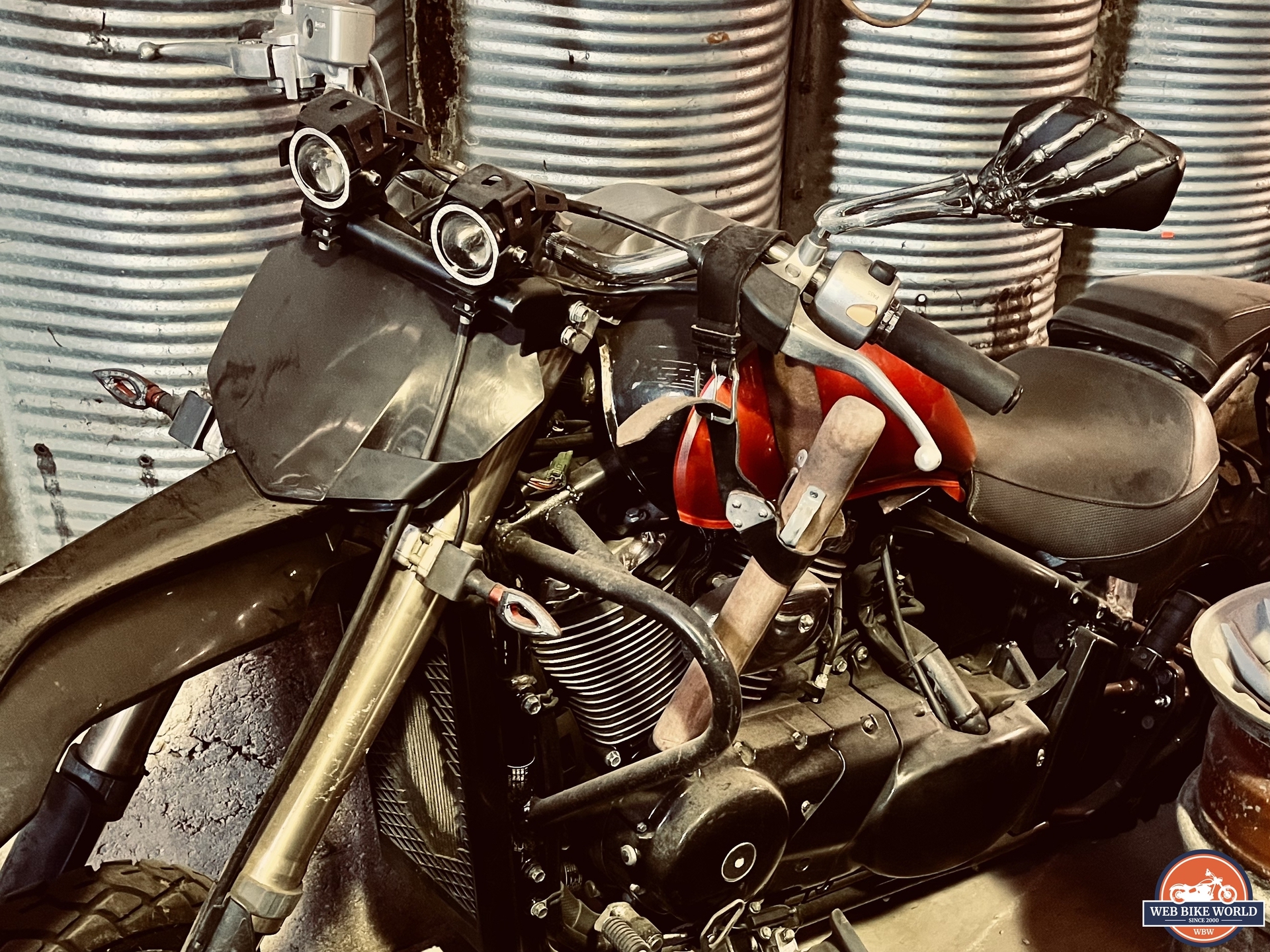

Grant’s three “Indian” motorcycles—actually Kawasaki Vulcan 800s retrofitted with a variety of American (or custom handmade) components.

Japanese Indians in Canada: Three Bikes with Truly Unique Origins

“I build Indian clones”, says Grant when asked about the highlights of his collection. “I started building them for The Man in the High Castle.” For those who aren’t familiar, the series takes place in an alternate-reality version of the 1960s where the axis powers—Nazi Germany and Japan—won the Second World War.

Given that information, it makes a certain kind of sense that Grant’s “Indians” are actually Japanese bikes—Kawasaki Vulcan 800s decked out with American parts. I ask if this was a creative choice to establish the bikes more authentically in the world of the show, but Grant explains that it had nearly as much to do with practical considerations. The production had originally tried using original vintage Indians, he tells me, but the stunt people had trouble riding them because of their kick-starters, left-hand throttles, and tickler carburetors.

“The last Indian bike was built in ‘53, and the last new model came out in ‘47,” he says. “So that’s the era you’re looking at for those bikes—you’re not gonna find a 1963 Indian, because they didn’t exist. But when you go back that far, the bikes are virtually unrideable for someone who didn’t grow up with them.” Vulcans, by contrast, can be retrofitted to look virtually identical to classic US cruisers, but are substantially more economical and rider friendly (a fact I know from experience).

See Also:

Grant’s workbench is littered with tools, towels, and spare parts—like the rest of his workshop, it’s the environment of a man so familiar with what he does that he seems to navigate more by intuition than any obvious set of organizing principles.

So Grant and his son, who’s also a mechanic and racer, went to work. The three Vulcans got new seats, tanks, bars, and pipes—one set of which the two actually made from scratch. After the work was done, the bikes went to a nearby auto body shop to receive a faux-patina that would make them look older and more rugged. “Real post-apocalyptic stuff”, as Grant puts it.

Two of Grant’s custom bikes, including a Yamaha Road Star 1600 (left) used for one of the Predator films.

Predator, Deadpool, & Beyond

The three Indian clones are far from the only bikes Grant’s doctored for highly-stylized productions. Along with a slew of smaller projects, he’s also built bikes for major motion pictures in franchises like Predator and Deadpool.

Not all of these are what you’d call picture bikes. Grant shows me a Yamaha Road Star 1600 that was hired out to one of the Predator movies but never actually appeared in the final cut. “But that’s the life,” he laughs. “You know how it is sometimes—you work your ass off for a perfectly good scene and it ends up on the cutting room floor.” Apparently, this happens to bikes and other props about as often as it happens to performers.

See Also:

Some of the strangest and most intriguing bikes in Grant’s collection are for movies and TV shows I’ve never heard of. “What a beast,” I say, walking over to an absolutely massive motorcycle that appears to be a kind of Frankenstein Monster cobbled together from parts for several different vehicles.

It’s the subtle details—like those giant silver skeleton hands on the mirrors—that really sell this one.

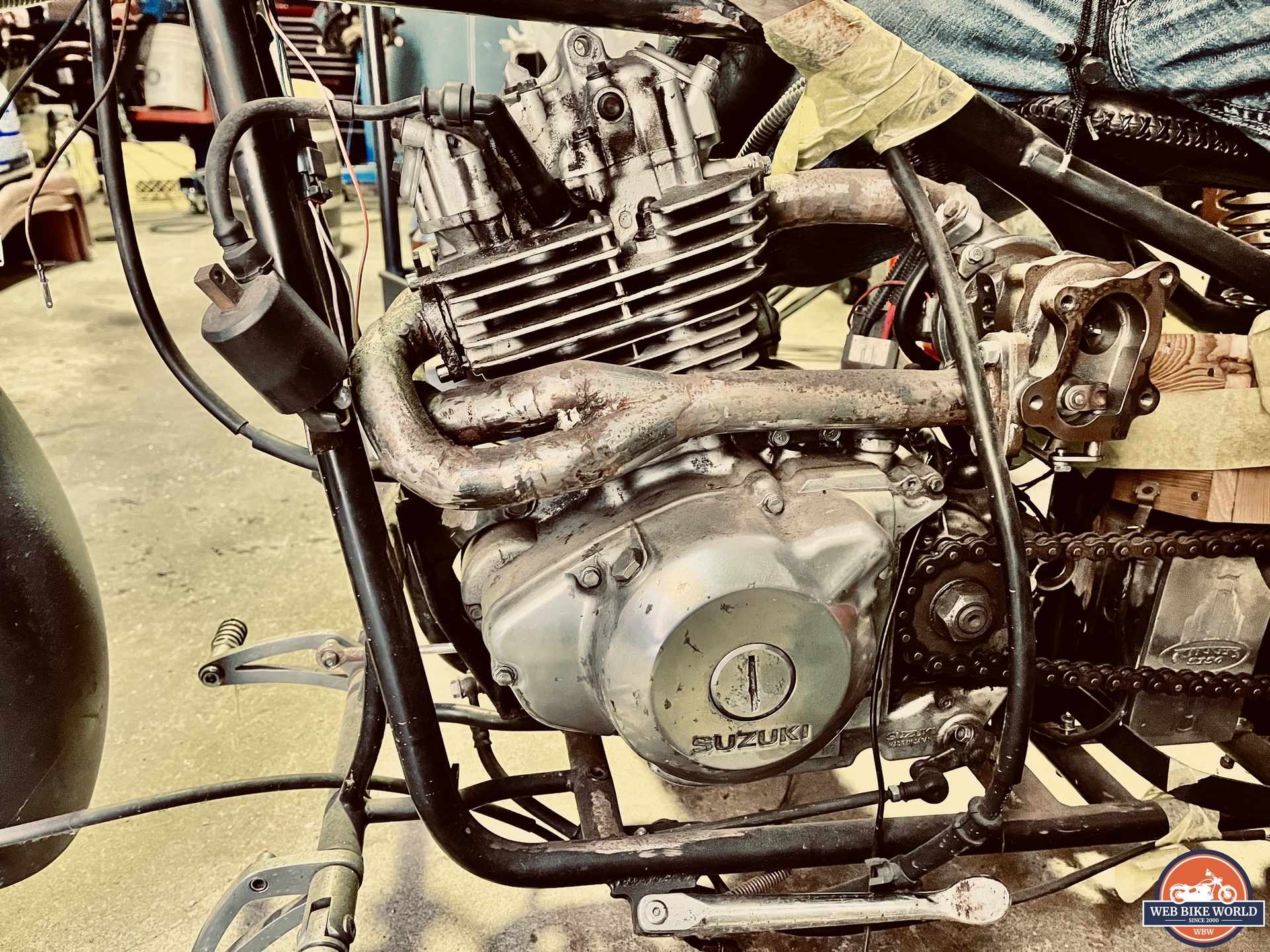

“This was for an independent zombie picture,” Grant explains. “The rear tire is an off-road ATV tire—just huge. And yet, it rides beautifully. The bike was originally an 800 Suzuki Boulevard C50, but the front end on it came from a Husqvarna dirt bike.”

Bill Hutchison, a contact of Grant’s from 6th Gear, was responsible for the initial build, while Grant took care of the final modifications to create the bike as you see it now. “When it’s in full trim,” Grant says, “there are also throwing axes that mount to the gas tank and throwing stars that go along the handlebars. The headlights are HIDs, and they strobe.”

See Also:

Hey, that’s not a motorcycle tire!

But Grant’s projects come in all shapes and sizes—one of his custom-built cruisers is so small he can lift the entire front end off the ground by hand. “This is a 7/8th scale chopper,” he says. “It’s absolutely tiny—which makes the rider look enormous. That’s why it was built.”

And you thought your custom Suzuki was lightweight!

“It was for a project that never happened,” he explains. “They wanted the rider to look gigantic—he was a big guy to begin with, but they wanted him to look even bigger. So it started out as a kit we found,” he laughs, “but then we modified the hell out of it because it was a piece of s***. The front neck assembly is off of a 250 Suzuki, as is the motor. But it’s turbocharged, so it actually goes pretty good—it’s a fair amount of horsepower for 250cc!”

Tiny, but turbocharged.

How Grant Moves His Creativity from Movies to Motorcycles

You’d never see this stuff anywhere else; Grant is one of the only people in the Pacific Northwest who’s doing what he’s doing. “It’s as much of an art form as it is a culture,” he says. “Building bikes is a huge artistic outlet; to be able to put something together and ride it”.

Lots of custom builders describe their work as art—but when you’re creating one-of-a-kind models to fit within the world of a specific movie or series, Grant believes his performing arts background is a major asset. After he finishes showing me his workshop, we chat briefly about life as an actor and how it’s informed his approach to working on bikes for different productions.

Grant’s career in front of the camera has been pretty prolific. Long Lost Christmas is one of the bigger things on his resume so far, but he’s also been in a number of projects you won’t see on the Hallmark channel. Take Shadow of the Rougarou, for instance, an APTN miniseries set in Canada in the 1800s where he plays a ruthless fur trapper stalked by a monster from Indigenous folklore. Needless to say, it’s substantially grittier fare.

Grant (fourth from left), surrounded by his fellow cast members for Shadow of the Rougarou. Via APTN.

But being a storyteller with that kind of range means you have to be thoughtful, sensitive, and versatile—qualities that have also helped Grant in his bike building. He’s passionate, but flexible; while some customs shops live and die by their design principles, Grant demonstrates an ability to create truly unique machines while maintaining a willingness to accommodate the specific needs of each production that hires him.

Striking this balance, he explains, is something he’s learned largely from working in the arts. “Artists can’t be rigid or one-dimensional,” says Grant. “The more you learn, the more valuable you become.”

With that kind of intellectual curiosity and sheer passion for his work, it’s no wonder Grant’s managing to thrive simultaneously in not one, but two careers—film actor and custom motorcycle builder—that most people would consider dream jobs. We look forward to seeing whatever he makes next, whether in his workshop, in front of a camera, or both.