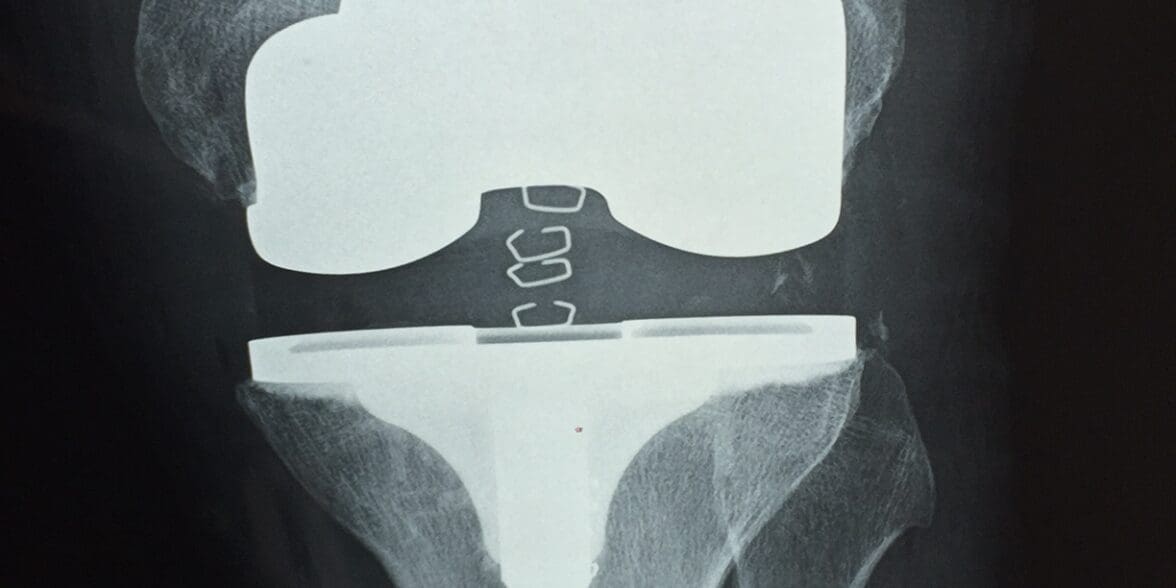

My first ride on a motorcycle after almost a month recovering from surgery for a new, bionic knee (see photo above) taught me four valuable lessons about riding.

How to get back on the bike after surgery or a crash

One lesson

First, I love it! The acceleration. The noise. The mastery of the controls. And the wind smashing against your arms, body and legs is a far better “drug” than anything the nurses pumped into me while in hospital.

Two lessons

Second, I found that I had developed the bad habit of relying too much on engine braking and not using my rear brake enough.

Let me explain.

I had decided I would ride again as soon as I could bend my left knee far enough to put my foot up on the footpeg.

Every morning, when my knee felt better after a night’s rest, I would go straight to the garage and sit on my Bonneville T100 and try to lift my left foot on to the peg.

However, I cut that short when my neighbour offered me a ride on her Indian Scout Sixty with forward controls. You don’t have to bend the knee near as far!

So, 25 days after having my knee sliced open and bones ground down to fit titanium pieces that look like pistons, I took my first ride.

I could reach the Scout’s footpegs easily enough, but it still hurt like fury to change gears up and down.

However, muscle memory is a funny thing. My left foot kept wanting to change gears frequently, especially through a series of messes on Mt Glorious, and my right foot wasn’t activating the rear brake.

The rear brake is there for a reason, so I had to consciously re-train myself to use it.

If used in conjunction with the front brake and the right gear, the rear brake does a great job of settling the bike dynamics through a corner.

Three lessons

The third lesson I learnt is that you don’t need much strength in your legs to hold a bike upright.

At its precise balance point a bike actually weighs nothing. You can hold the biggest bike upright with only one foot on the ground.

When you stop at traffic lights or a stop sign, you should put your left foot down and cover the rear brake in case you get shunted from behind. It will help prevent you being thrown forward into oncoming traffic.

The first time I stopped, I pulled my left foot off the peg too soon and when it landed it went down with a thump and the bike pitched on to my bad knee.

It was excruciating, so I decided to think more carefully about stops.

After that, I didn’t take my left foot off the peg until the very last second and thought about keeping the bike close to its balance point.

The result was that my foot touched down much more gently and the bike was still upright and secure.

Read how to avoid ‘pelican landings’

Four lessons

In the past couple of decades I’ve only ever been off a bike for more than a week on the two occasions I crashed and was recuperating.

This time, it was a voluntary decision to undergo knee replacement surgery after damage caused by years of running, and playing soccer and squash.

I could barely walk, but it was actually the fact I couldn’t ride for long without getting a painful left knee that finally convinced me to have the knee replaced.

It was a difficult decision. I knew of the pain coming as I’d had knee repairs performed before.

But the real reason it was a difficult decision was that the doctor told me I wouldn’t be able to ride for three months.

So here’s the fourth lesson I learnt that has nothing to do with motorcycles. If you diligently do the daily physio exercises, no matter how painful, and ice the knee as often as possible, you can reduce the recovery time substantially.

Actually it does have a lot to do with motorcycles: There is no greater motivation to do those painful exercise than the thought of riding again!