It’s something that we take for granted these days: that 99.9% of the jackets, gloves, pants, and boots we buy to ride in will have some form of CE Level 1 armor. We expect it at the heel and toe, over the ankles, and at the knees, elbows, and shoulders. In fact, it’s become so ingrained into the sport and hobby of riding that it doesn’t seem real that not even 50 years ago, even the concept of dedicated motorcycle riding gear outside of tourist trophy and grand prix racing was yet to be established.

With the motorcycle now approaching 125 years old, that means that helmets, riding gear, and eventually armor all came about in just a third of the total time since Hildebrand & Wolfmuller sold their first production motorcycle. The fact that in one third of the motorcycle’s total lifespan, research and development has proceeded at a pace rivaled only by the explosive development the motorcycle itself experienced through the 1970s to give us all the major niches we have today is astonishing.

As such, let us take a look back through history, and investigate just how we got to where we are in terms of personal protective equipment—plus, we’ll look at the new technologies and materials that are still being invented or discovered to this day.

Origins: Cafe Racers, Leathers, & British Motorways

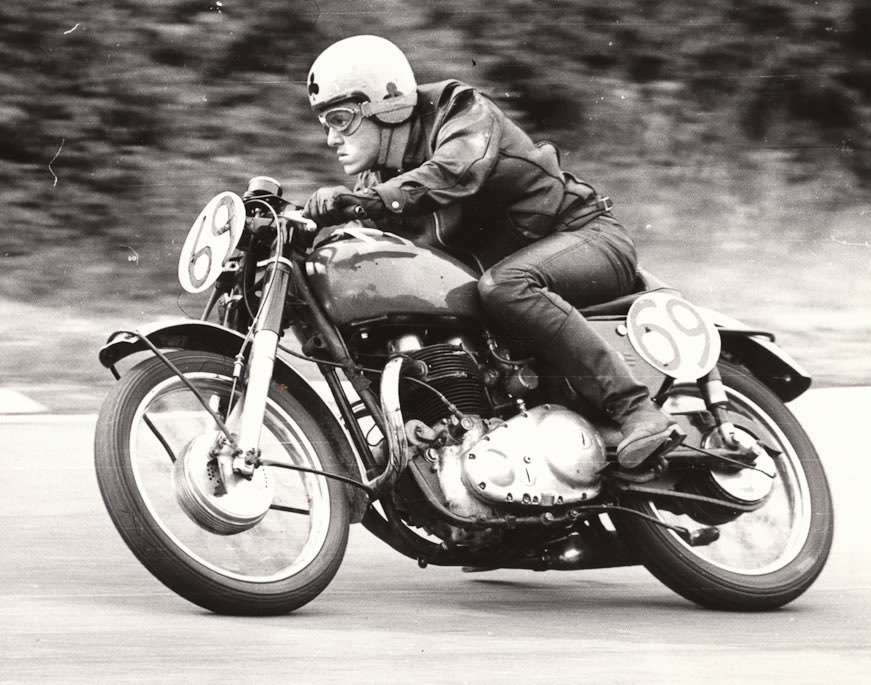

To be completely frank, if the entire cafe racer movement of the 1960s and 1970s had not happened, motorcycle armor would have probably not developed as quickly as it did. These were the original speed freaks, the guys (and a few girls) that modified their bikes and would race them down the British motorway system in short sprints. It was these brave—and sometimes completely insane—souls that pushed motorcycles to speeds never reached before cafe racing.

It was through cafe racing that the first motorcycles capable of sustained speeds over 100 MPH were brought about. While some bikes before the 1960s could reach 100 MPH, they would only last a few miles before overheating or suffering a failure of some kind. It was also through those sustained high speeds that accidents started to happen, where a racer would lose control and crash, or have a tire blow, or be subjected to any of a hundred different scenarios, and would go sliding, tumbling, or cartwheeling down the pavement.

In the aftermath of some of those crashes, the uniform of the cafe racer changed. It started out with a leather riding jacket worn zipped up and fastened tightly, and cafe racers were also some of the first to make consistent and regular use of helmets. Leather driving gloves started to get bought up in droves to protect riders’ hands, and soon, motorcycle specific gloves appeared on the market.

Full leather race suits, once thought only necessary for things like the Isle of Man TT, became the thing to have if you were seriously into going the maximum speed to get the minimum time between checkpoints.

Throughout the 1970s, specialist gear manufacturers started to appear. One of those companies was started in 1972, in Colceresa, Italy, by one Lino Dainese, who was only 20 at the time. The first piece of gear made was a set of leather motocross pants, but soon enough, there was demand for his gear in other forms of racing, as he actively promoted the use of protective gear and rapidly adjusted his production to target as many of the blossoming markets as he could.

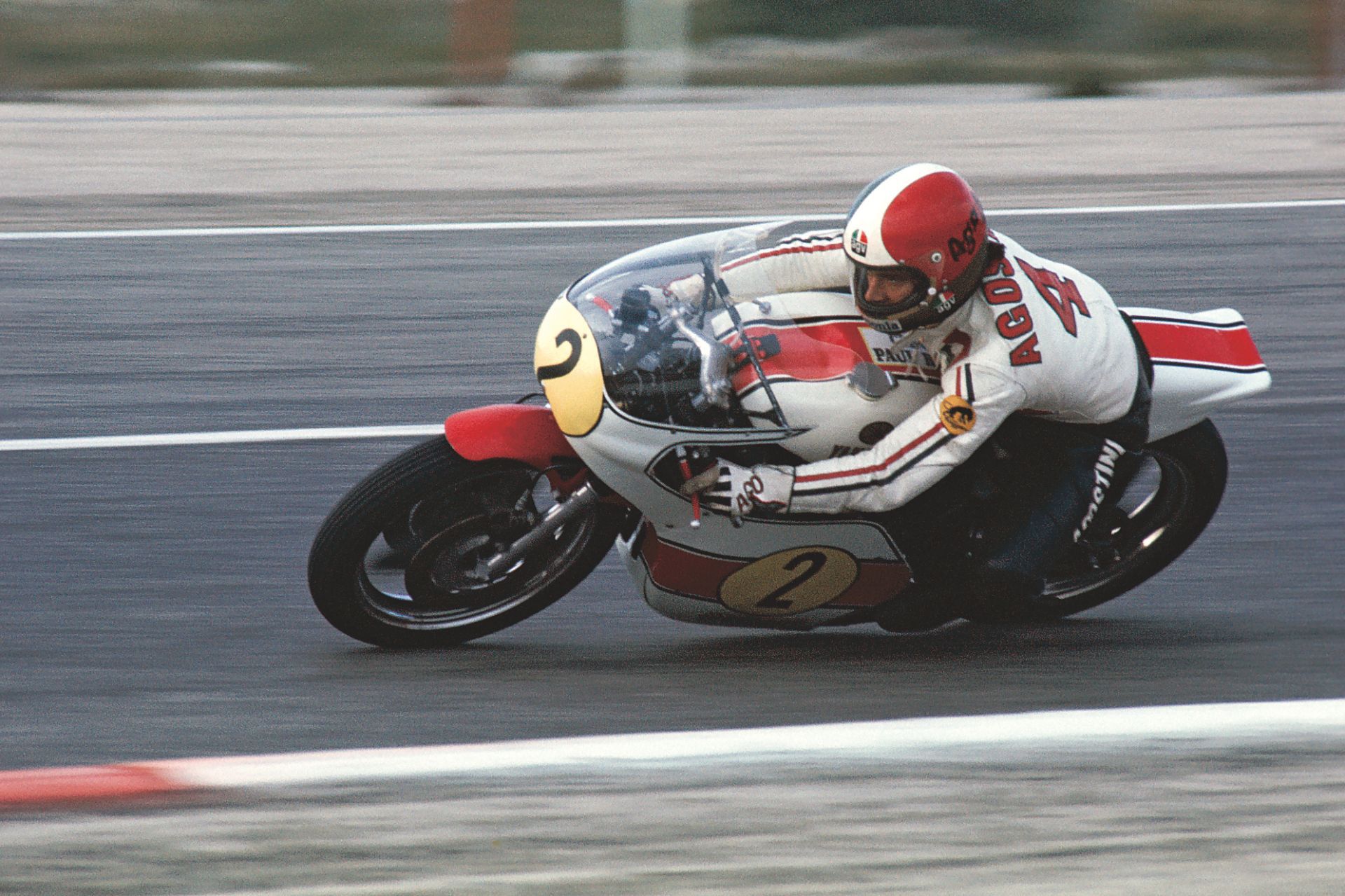

In 1975, 15-time world champion racer Giacomo Agostini became the first professional rider sponsored by Dainese, and raced in a full set of leathers produced for grand prix-level use. As the cafe racer movement, now a global one, started to slowly lose steam through the 1970s, those who were still dedicated to the cause would almost always be seen in a set of Dainese leathers.

Flush from the sales of so much of his gear, Lino Dainese tasked his design teams to start to think about more than just the leather that a rider would wear. Was there any way to increase the protection without increasing the bulk? Was there any way to prevent riders from getting abrasion burns through their leathers as they slid out in a crash? What could be done to protect the riders’ backs and spine? That last question, the most pertinent one, was the one that started everything.

Armor Through the Years

The year in question is 1979, and Dainese designers, tasked with the questions listed above, were deep in thought about how they could add more value and protection to their products without sacrificing comfort or being ridiculously bulky. No one knows for sure how it started, but one of the designers, for some reason, thought of a lobster, and the light bulb went off over their head.

Lobsters have, as you well know, articulated but armored tails. If they didn’t, they wouldn’t be able to “leap” forward to catch prey in their claws with a solid kick of their tails. This armor is a series of rigid, interlocking plates, evolved to be strong yet lightweight. In the second half 1979, Dainese released the first ever motorcycle back protector, a series of rigid interlocking plates made of strong but lightweight plastics, backed by impact foam.

Of course, it didn’t sell well at all. Few riders wanted to think about wearing “armor” to go riding, and while the more safety conscious riders, and a lot of professional racers bought and used them, it was still seen as a weakness to need to use armor to ride. One event, however, changed everything, and proved that armor was here to stay.

Lino Dainese, still passionate about motorcycle racing, insisted that any of the riders sponsored by his company wear the back protector under their leathers. Since the Italian gear manufacturer was now bringing in serious sponsorship money for teams and riders, everyone agreed. One of those sponsored riders was Freddie Spencer, better known as Fast Freddie, one of the greatest professional racers of the 1980s, who was given a back protector just a few days before the World Championship round at the fast and technical Kyalami Circuit in South Africa.

Lino Dainese insisted that Freddie Spencer wear the back protector, and since he was sponsored, Freddie slid the armor piece into his leathers before setting off for the first practice session. As he was going rapidly down one of the straights at the circuit, the carbon back wheel of his Honda race bike exploded, sending Freddie into an almost immediate highside. He came down hard, directly on his back, on one of the curbs that denote a corner, which was a raised bit of tarmac in those days.

Spectators held their breath, as it was commonplace to see riders that had crashes as severe as that one being stretchered off the course in pain and sometimes paralysis. To everyone’s shock and amazement, Freddie stood up. Not only that, he then proceeded to walk off the track, no sign of injury at all. Pulling the back protector from his leathers later, it was clear that a couple of the armor plates had cracked, but his spine was uninjured.

Since that day, armor development has proceeded at a rapid pace. Other motorcycle gear manufacturers, such as the newly created motorcycle gear department at Alpinestars, started to research and design their own back protectors. New materials were researched, such as viscoelastic foam, hardshell plastics, and even lightweight aerospace grade aluminum in the same lamellar style as that first back protector from Dainese.

Motorcycle leathers also received a massive rethink, with the first knee sliders appearing as racing bikes got faster and faster, and deeper and deeper leans were needed to corner. Motorcycle gloves started to get hard plastic knuckles backed by memory foam—and by the mid-1990s, driven mostly by Dainese, Alpinestars, and the newly formed and popular Rev’It gear company, permanently attached armor, sewn into the shoulders, elbows, and even forearms of their first jackets set the standard that we now expect every gear manufacturer to follow.

The original armor in the Rev’It gear was often a hard plastic backed by comfort foam, or in the higher-end pieces, aluminum backed by that same foam. But the next major discovery was that there was a certain type of plastic that could be made malleable or rock hard—and when used in its soft, malleable form, it showed excellent force distribution. Given a hard enough whack, it would even shatter itself to dissipate energy.

That material is known as thermoplastic polyurethane, also known as TPU. Soon, it became the material of choice for back protectors, elbow armor, shoulder armor, boot armor caps, knee sliders, and the whole lot. No one truly knows who discovered that it was excellent material for motorcycle gear, but in the space between 1995 and 1998, it was suddenly in everything.

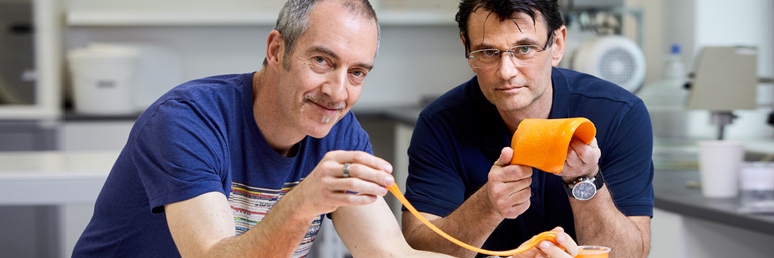

Just before the new millenium, the next step in armor came from, of all places, a pair of snowboarders. Richard Palmer and Philip Green were material scientists by day, and skilled snowboarders on the weekends. During their day job, they had begun experimenting with a dilatant (rigidity induced by shear forces) liquid that was showing non-Newtonian properties. The liquid could be handled, poured, and sloshed around like water, but the moment it was forcefully struck, it went instantly rigid and became a solid.

Inspired by their snowboarding hobby, the pair drew inspiration from the natural shape of snowflakes, and mixed the liquid with polymers to make a flexible, rubbery plastic material that was a matrix of hexagons. It moved with the body, but the instant it was struck, it went stiffened. As the matrix was a set of hexagons filled with triangles, one of the strongest shapes in nature, it only added to the ability of the armor to both take and distribute the energy of impacts.

They incorporated their new material into their snowboarding jackets, and found that the material was extremely light, moved with the wearer, but would also “take the hit” for them when they wiped out or sometimes intentionally fell over to test it. After filing a patent for their newly discovered material, D3O was born.

Motorcycle gear manufacturers almost immediately saw the benefits of the stuff, and within a year of the patent, D3O armor was being proudly incorporated into gear by Icon, Alpinestars, KLIM, and pretty much any other name you could think of.

This inspired some of the big companies to invest heavily into non-Newtonian materials, with Alpinestars developing their Nucleon series of armor pieces by the end of the first decade of the millennium. However, there was another newly established gear company (originally to make snowmobiling gear) that innovated the “next big thing” in armor, and carried us to where we are today.

The Present & Future of Motorcycle Armor

KLIM, founded in 1999, saw the efficacy of non-Newtonian materials—and although it took them a long time to develop it, around the year 2010, they released the first versions of what came to be known as impact foam. Unlike the soft foams of previous gear company products that were used to back the armor in gear for comfort, this time around, the foam was the armor. By making a lightweight foam out of non-Newtonian materials, their gear was ultra-lightweight, but still offered the same level of protection as D3O or TPU.

Soon, other manufacturers were on board with the ultra-lightweight foam, with Rev’It innovating an entire series of back protectors made out of tightly married plates of impact foam. But KLIM wasn’t done innovating yet. Their most recently-developed armor, which appeared just a few short years ago, Poron XRD, was the evolution of the original non-Newtonian impact foam.

Poron is packed much more tightly together at a molecular level, using a different set of materials than the original foam, but is extremely lightweight. It allows air and moisture to pass through it, yet will go harder than carbon steel when impacting something.

Looking back through those breakthroughs, it’s clear that armor is showing no signs at all of slowing down when it comes to innovation and evolution. We’ve come this far in just over 40 years, so what are the most likely steps that are going to be taken in the next decade?

There has been some serious research and development recently into interweaving non-Newtonian foams with a fiber known as Dyneema. It appears to the naked eye as a sort of denim, but don’t let that fool you, as the material is 15 times stronger than steel, 40% more effective at dissipating energy than aramids and Kevlar, naturally waterproof, and won’t fade or break down under intense UV. It’s also light enough to float on water, and is naturally oleophobic and chemical resistant.

Dyneema has been used in motorcycle jeans for a few years now, often backed by an aramid or Kevlar layer, as it provides 5x the abrasion resistance than normal denim does. If you were to slide in equivalent thickness denim jeans and Dyneema jeans, you’d wear through the denim in half a second, whereas you get just short of 4 seconds of wear from the new material.

The thought is that with the strength of Dyneema mixed with the non-Newtonian aspects of impact foam, a super-lightweight armor “sandwich” can be made, with alternating layers of foam and Dyneema. As impact foam is extremely flexible, and Dyneema is a woven fiber fabric, the armor would naturally follow your body movements even better than impact foam or D30 alone. When you take a fall however, it would provide an extra layer of abrasion resistance comparable to that of cowhide, and the impact foam would take the energy of the impact and distribute it across the entire sandwich.

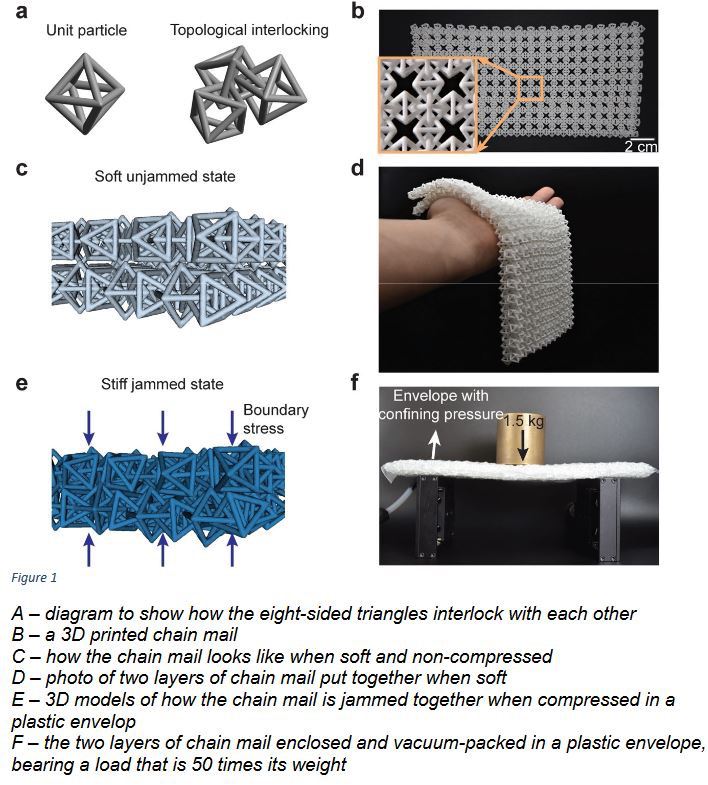

Another interesting form of armor currently being investigated by scientists at CalTech and NTU Singapore is a new type of fabric that is essentially a series of 3D-printed, interconnected octahedrons using a chemical composition that makes each octahedron act the same as non-Newtonian foam. The current working name for it is “Structured Fabric,” and it acts like D3O armor does, but is as thin as a normal cotton t-shirt. In essence, you could ride in a hoodie made out of structured fabric, and instead of incorporating armor into the hoodie, the hoodie would be the armor. Cool stuff.

What is exciting about structured fabric is that it is also tuneable. For example, along the forearms, the elbows, the shoulders, and the spine, you could have the fabric woven in such a way that upon impact, it would go as hard as steel, while the underarms and sides of the body could be tuned to be less stiff. Another amazing property about the fabric is that it is as abrasion-resistant as natural cowhide, yet as flexible as cotton.

If you’re really into the science of it, there is a very complicated and in-depth research paper about it here: NTU Singapore Structured Fabrics Paper.