To think, if you went back even 15 years through some kind of time travel and told the motorcycling masses that electric motorcycles not only exist but might even be the future of riding, you would probably be laughed at. However, here we are, in a time and age where the Big Four out of Japan have made a historic battery-swapping agreement to share battery technology across their brands. While this is mostly for scooters, which are much more prevalent in packed, tight cities such as Tokyo in Japan, the technology is pretty much ready-made for electric motorcycles.

This poses some interesting questions, as most electric motorcycles these days have their batteries built in, with various levels of charging from normal to supercharging available. Companies such as Livewire, Zero, and Energica have their bikes set up this way, but is there actually space in the market for a motorcycle that might take 2 or 3 interchangeable battery packs to run? Or is it better to have a big built-in battery and charge it up when you need to?

It is because of these questions that we’re going to take a look at how both systems operate, dig into the actual costs of each approach, and investigate why both approaches have some really big positives and negatives.

Why Both Systems Are Viable

To answer the first question of there being space in the market, we first need to investigate the viability of both systems.

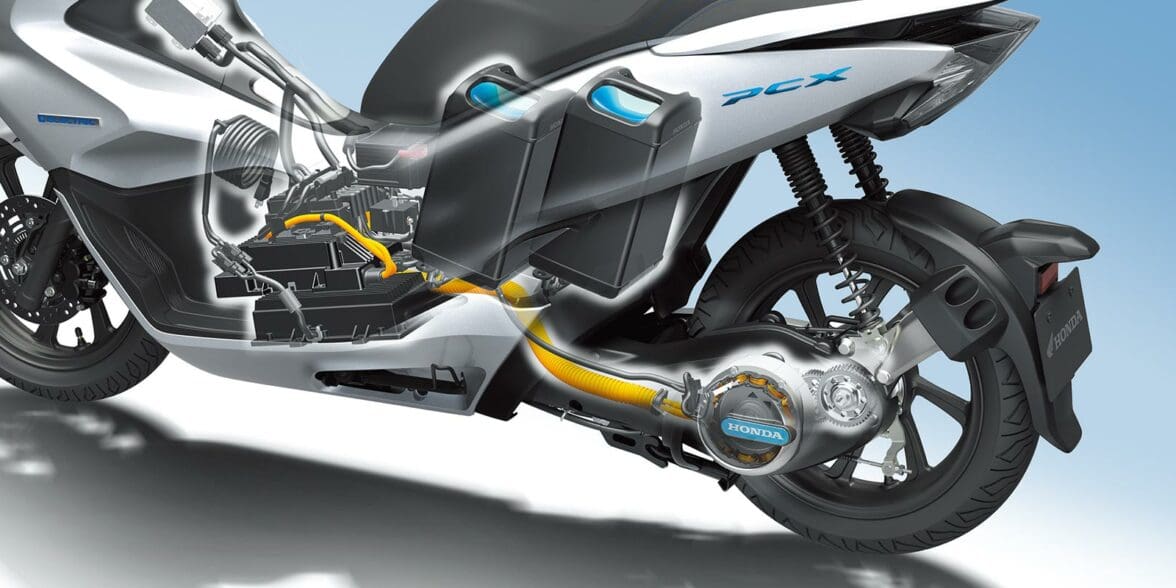

For built-in batteries, the big draw here is that they can hold a larger charge than a size-limited swappable battery. You will see this on most bikes as having multiple “range” batteries, such as normal range, extended range, extended range plus, and the like. Some will simply involve a bigger battery in the bike, while others will add a secondary battery up under where the fuel tank would be in a normal bike.

The counter-effect of putting a bigger battery in a bike is that batteries, by their very nature as densely packed items, are heavy, and the more battery you have, the higher up the bike the center of gravity will move.

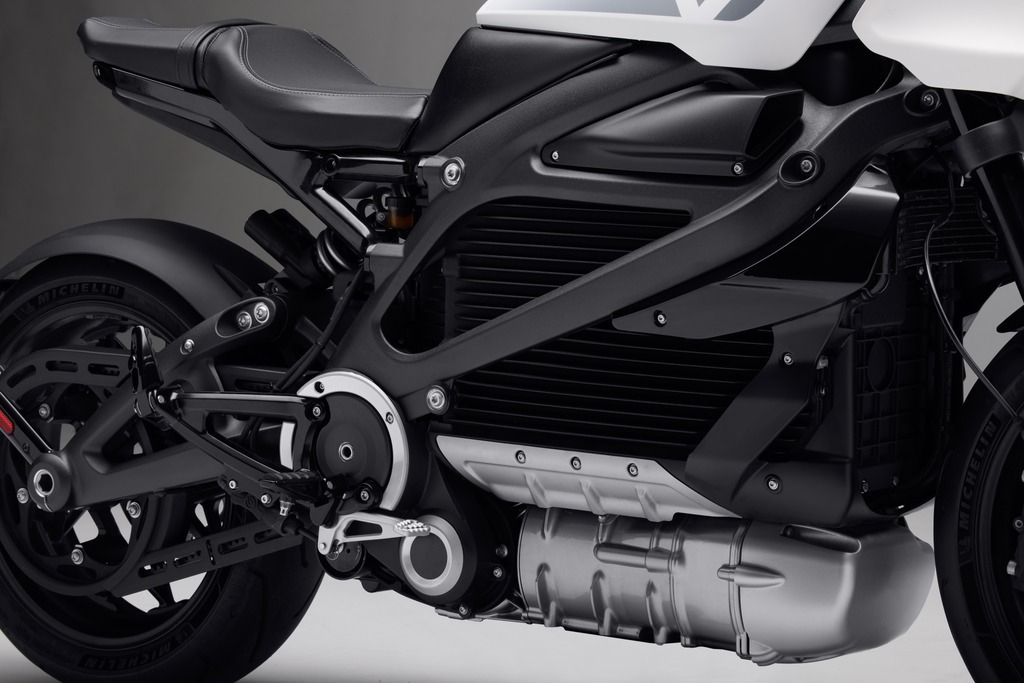

For built-ins, their other major benefit is that since they are a permanent part of the motorcycle, heavy-duty charging cables can be routed to them. This is why some electric bikes, especially those with extended ranges, are high-charge and supercharger-compatible or can be hooked up through a home charging station on 240V power.

Since these batteries are also smaller than what most electric cars carry, they won’t need as much time at the charge station to top off, with the downside that even with supercharging, it might be a 20 to 40-minute wait at the charge station.

It is for that exact reason—wait times at charge stations—that the Big Four banded together to make the Gachaco swappable batteries. In much the same way that a lot of households in the US will have a set of rechargeable AAA’s or AA’s for things like wireless mice, TV remotes, console game controllers, and the like, the Gachaco system is just the same idea, but on a macro scale.

When you’re low on your battery pack, say 15% or so, you simply go to the nearest service station with a Gachaco rack, pull the battery from your scooter, slot it into an open charge space, pull out a fully charged battery, put that in your scooter, and off you go again with 100% battery. In places like Tokyo or Osaka in Japan, or Los Angeles or New York City in the USA, this kind of a-la-carte battery swapping makes complete sense.

The benefit here is that you don’t need to worry about home charging at all, even though you will be able to buy home chargers for the Gachaco system. Simply ride down to the gas station with a battery rack, or a charge station with a few racks, and swap out the batteries.

This also works well for motorcycles, since the battery packs as they are are small enough that you could put two or even three in line under a flip-up fuel tank cover, and have a day’s worth of light riding, or a half day’s worth of canyon carving with your electric bike. Also ensuring that you need to slot in a battery to recharge before you can take out a charged battery means that in most cases there will always be batteries ready to pull from a Gachaco rack.

Which Is the More Affordable Solution: Investigating the Actual Costs

The biggest thing in most people’s minds when thinking about electric vs gas-powered vehicles is cost. That’s why some of us who want a big, powerful Kawasaki Ninja ZX-10R will instead settle for a Yamaha R7 or Kawasaki ZX-6R. They’re all fast bikes, but the latter two are gas sippers against the ZR-10R, which can down a tank of gas on some happy throttle at a track or a canyon in just 150 miles traveled, if that. In that vein, which of the two systems, charging versus swapping, actually has the better cost?

This is actually a bit more complicated than it seems on the surface. While there is a fixed rate at most charge stations per kWh recharged on each level of charging (normal, fast, super), do those values also apply to a swappable battery? In other words, while the entire reason that the Gachaco alliance was made was for easy swapping, who is paying for the electricity to recharge a drained battery pack?

As far as we can find out through some pretty extensive research, there are two solutions to the swappable battery question. One is a system already in use in Taiwan with their very-similarly-named Gogoro eScooters. You can either buy an eScooter or rent-on-the-street, much like Car2Go or Lime in US cities, and pay a subscription fee per month or per year.

There are multiple tiers of subscription, from low-cost flexible plans perfect for someone doing only a few swaps a month, to high-usage tiers for someone that is swapping every day. Using an app on a smartphone and NFC, or a Gogoro prepaid card, you slot your drained battery into the charging wall, tap when the system prompts you, and if it sees you have a valid subscription and enough money on the card, it pops out a fully charged battery for you.

From what we could find from Gogoro’s own website, a “high usage” flex plan, which encompasses 600 KM (373 miles) and charges NT$2.3 per Ah used, is NT$1,269 per month for the base subscription. In USD, those values are 7 cents per Ah used, and just about $42.70 per month, which translates into “mighty affordable.”

Each swappable battery carries 1.3 kWh of charge, which is more than enough for an eScooter to get around for quite a while, and assuming you swap every other day, for 15 days per month, that adds only $1 to $2 a month on top of the subscription fee.

For bikes that have a built-in battery, using as an example a Harley-Davidson Livewire One, the kWh of the battery is the biggest draw. Instead of using a small 1.3 kWh pack, the Livewire One has a 15.4 kWh battery built-in and is equipped to charge from a 120V wall socket in 11 hours, or 0% to 80% in 40 minutes on a 400 Volt DC fast-charge station.

For those looking to charge at home, according to Business Insider, the average rate per kWh in the US for 2021 was 13.73 cents, meaning that to charge the Livewire One overnight on the 120V wall charger from absolutely drained to 100% would be $2.10. If you ride daily as a commute, with an average of 20 business days and one or two Saturday rides a month for 22 total days, you’re looking at $46.20 per month.

The real cost comes when you access a DC fast-charge station, with the average cost there being 25 to 30 cents per kWh, with some very high-traffic regions being much higher. The reason for the added cost is that charging stations themselves are not exactly inexpensive and have to be paid for, and the infrastructure to ensure that high voltage electricity is safely provided may have had to be built before the charge station could be put in place.

While you do get a much faster charge (40 minutes instead of 9 hours for 0% to 80%), if you charge all 15.4 kWh of a Livewire One, you are looking at a median average of $4.21 for a “full tank.” If you follow the same 22-days-a-month schedule as the home charge, that’s $92.62.

Potential Issues with Both Systems

As seen in the investigation above, what really drives the price you are willing to pay for charging versus swapping is convenience, first and foremost. However, the elephant in the room is the type of motorcycle actually in use.

The biggest known issue with the swappable battery packs is that they carry, as stated, only 1.3 kWh of charge. For something like a small Yamaha or Honda eScooter, with a 2 to 4 HP DC motor, that’s plenty. For a Livewire One, which has a DC motor that is equivalent to 100 HP, that’s enough to get you down the street, around the corner, and maybe a few miles after that.

If you had a much more lightweight motorcycle, such as a Zero FXS, even the base spec there carries a 3.6 kWh battery and has a 36 mile combined range city/highway.

Realistically, it would be a supermoto or dual-sport bike that would benefit the most from swappable battery packs, but as they are already carrying twice the weight of an eScooter, it would affect the range just as much. To get to the same 3.6 kWh on the FXS, you would need three battery packs, which also would add a touch more weight than the built-in battery. It’s one of those cyclical issues where there are benefits to one side, but it brings up more issues on the other side.

The biggest issue that arises with built-in batteries is that unlike the swappable battery packs, there is no “I need it now” recharge option. Even the top tiers of EV motorsports, Formula E, Moto E, and Extreme E Rally, with 900 Volt or higher superchargers, still need at least 30 minutes between heats to recharge to at least 80%. Since the Livewire One does not have a Tesla supercharger compatible connector, as it uses the CCS1 EV connector, that means if you are riding and hit 5% battery, better bring a lunch along because you’ll be sitting around for at least 30 to 40 minutes at the highest charge rate a CCS1 can handle (400 Volts).

Both systems have their pros and cons. Swappable batteries and eScooters make much more sense for densely packed cities like New York in the US, Toronto or Vancouver in Canada, and the like, and if you outright buy one, it’s much cheaper than buying an electric motorcycle. The flipside is that to use it, you’ll be paying a subscription fee or a per-swap fee. Built-in batteries carry much more charge, and while heavier, have a longer range than most eScooters have unless you are pinching pennies and get a low-range motorcycle.

Things are looking good in the future, however, as battery power density is becoming a major area of interest to many car manufacturers that are bringing out EVs before 2030. The more energy you can pack into a smaller area, the better efficiency you will get out of a battery. Density is one thing, the battery materials are another, and advances there include graphene, lithium-tungsten, and even sodium-based batteries that hold more charge than the standard lithium-ion batteries of today. Then there is the whole discussion to be had about hydrogen-powered cars and bikes, which really is an article in itself. Even sustainable ethanol fuels could enter into the discussion.

Ultimately, it’s like the old adage says: “Wait and see.”