BSA A65: THE MOVE TO UNIT CONSTRUCTION

The BSA A65-A50 twins, the A65 being a 650 twin & it’s smaller sister-bike the BSA A10 500 twin, were the natural result of the trend, then sweeping the British motorcycle industry, to unitize engine construction. Prior, most engine packages were made up of separate crankcase, primary case & gearbox, all bolted together in mounting plates inside the frame. Known then as Non-Unit construction, now as Pre-Unit, it had evolved from the earliest days of the motorcycle industry, when it was common for a motorcycle company to outsource engines & gearboxes from other firms & adapt them to their cycles. But, by the late 1950’s the major makers were all using their own standardized components & the move was made to make engines lighter, more compact, stronger structurally (in theory, allowing more power with less vibration & flexing) & cheaper to produce. Hence Unit-Construction, which placed all 3 component sets in one common set of cases. Triumph Motorcycles was one of the leaders in this area, converting first their 350cc 3T twin over to unit construction in 1957, followed by their 500cc 5T twin. The handwriting was on the wall: it was only a matter of time before they converted their 650 twin over as well (this would take place in 1963). It was clearly time for BSA Motorcycles to take their successful line of vertical twins, the 500cc BSA A7 & the 650cc BSA A10. Both used the same design that was launched back in 1947 with the original BSA A7 cast iron twin. So, work was begun in earnest to develope a Unit-Construction replacement for their venerable line of Pre-Unit Twins. These would become the BSA A10 500 twin and the A65 650 twin..

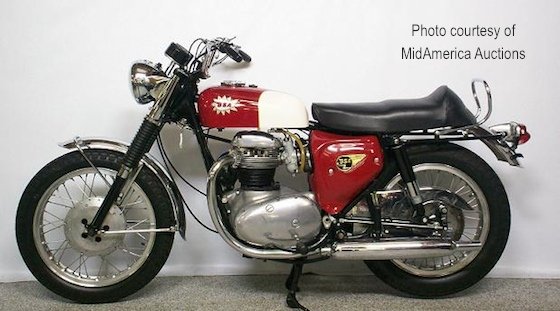

LEFT: Pre-unit Construction 650 twin, 1947-1963. This one is a 1960 A10. |

RIGHT: Unit-Constuction 650 twin, 1962-1972. This is a 1966 A65. |

THE POWER EGG, WHAT A CONCEPT

The late 1950’s were a time of great change in the British motorcycle industry, everyone scrambling for position, hoping to come up with ‘The Next Big Thing’. Triumph had nailed it twice, with both the TR6 & Bonneville. Norton had its Featherbed. And BSA had the Gold Star. The 50’s had been good to the Brits, but their was a change in the wind, a storm heading their way. One quirky trend that emerged from the turmoil was enclosing & smoothing motorcycles to make them more car-like. You only have to look at a Bathtub Triumph, a Vincent Black Prince, or a Velocette Vogue & you’ll get the idea. For whatever reason, it would appear that BSA decided to apply this same design logic to their new engine. They took what was an elegantly sculptured engine that was very pleasing to the eye, and turned it into a shapeless blob that had no visual appeal whatsoever. They called it “The Power Egg”. The Power Egg? The Power Egg. Go figure. The problem here is that, while you can quickly restyle a bike when trends fade, an engine isn’t easy, or cheap to change, especially in overall shape. The enclosure fad faded within a few years, never catching on in the US at all & all those enclosed bikes vanished from the marketplace. But the BSA A65-A50 Power Egg was still with us & would be, relatively unchanged, until BSA’s death in 1972.

ABOVE; 1966 BSA A65 Hornet 650 had high pipes for off-road work. The BSA A65-A50 made a pretty decent desert racer, back in the day.

THE SAME, BUT DIFFERENT…

The basic internal design of the BSA A65-A50 engine actually changed very little in the transition. The layout was the same: 360-degree one-piece crank with alloy conrods, single cam behind the cylinder block driven by a gear train on the right side, primary chain and clutch on the left with the same basic gearbox. All of this was tucked into a new set of unitized engine cases. These alloy cases were split vertically down the centerline, with the inner primary chaincase as part of the left crankcase half, & the gearbox housing part of the right. The two engines, the 500cc A50 & the 650cc A65, shared most parts in common, including their stroke, at 74mm. The A65’s bore was 75mm for a displacement of 654cc, and an nearly-square ratio. The A50’s bore was 65.5mm for 499cc. Both came out with single carburetors & alloy heads.

ABOVE: 1967 BSA A65 Spitfire Mark III with big tank.

MODEL PROLIFERATION

BSA A65-A10 model names during the unit construction era were many. The 500cc BSA A50 came in a variety of styles & names, including Star, Royal Star, Cyclone, & Wasp. The 650cc BSA A65 carried model names like Rocket, Thunderbolt, Thunderbolt Rocket, Lightning, Lightning Rocket, Lightning Clubman, Spitfire, Hornet, Spitfire Hornet & Firebird Scrambler. But no matter how BSA dressed them up, these new unit-construction twins never sold as well, or garnered the same respect as was accorded to the pre-unit bikes they replaced. They seemed to lack the character that the A7 & A10 had in spades.

FROM BAD TO WORSE

It’s hard to say what caused BSA Motorcycles to make so many missteps in this crucial era. While it didn’t look like much & didn’t sell very well, the unit-construction BSA twins were actually pretty good engines. The BSA A65-A50 had their shortcomings, but these were slowly, methodically being remedied in the normal evolutionary development process used by British motorcycle makers of the day. Weaknesses included an alloy oil pump (instead of cast iron) that would warp & thus fail to deliver enough pressure, & a scheme that delivered oil to the big ends via the timing-side (right) main bush & through the crank, leading to an under-oiled left big end bearing. At high RPMs, the already weak oil pump was trying to pump oil into the center of the crank working against centrifugal force. To make matters worse, in 1966 BSA replaced the drive-side (left) caged ball main bearing to a roller race. This removed the positive location of the crankshaft, allowing it to wander from side to side, quickly wearing out the flimsy shims & thrust washer intended to cope with the situation. This usually lead to a spun timing-side main bush, cutting off the oil supply to the crankshaft completely, breaking the crankshaft or conrods & shattering the cases. This has been solved today with modern-day solutions, but the BSA factory never seemed to get it quite right.

ABOVE: 1970 BSA A65 Thunderbolt.

LAST OF A BREED

1970 was the last BSA A65-A50 before the dreaded “Oil-in-Frame” bikes appeared. Many BSA enthusiasts felt the bit twin had reached its developmental zenith with the 1969-70s. They were fast, and fairly reliable. Most of the issues had been resolved. But they still had that stodgy old school-look about them. But that was about to change.

OIL-IN-FRAME FIASCO

In a stroke of particular stupidity, in 1971 BSA Motorcycles took their entire twin line (the BSA A65 and A50) and Triumph’s very successful 650 twins, and reintroduced them all with a completely new oil-bearing frames and cycle gear. This was an attempt on the part of BSA Motorcycles, the owner of Triumph Motorcycles, to modernize its product line and unitize as many parts as possible between the two brands. The new frames and cycle gear were shared in common between the BSA A65-A50, and the Triumph TR6 and Bonneville 650’s. A product of another of BSA’s horrendous follies, their overpriced and overrated ‘technology center’ Umberslade Hall, the new “Oil-in-Frame” machines arrived late and had major problems that had to be overcome before production could begin, which was delayed many months. It was found very late in the process, that the Triumph engines couldn’t be fitted into the new frames in one piece. The solution: remove the rocker boxes from the fully-assembled engines, stuff the engines into the frames, then reinstall the rocker boxes. Even this required completely revised rocker boxes and head bolts. This was the kind of foolishness that had overcome BSA Motorcycles at the time. Other things like a 34-1/2 inch seat height, flimsy wire headlight brackets and cheesy controls just went to show how clueless they were at the time. Despite all this, the new 1971 BSA A65 was a handsome machine.

ABOVE: When the ’71 BSA’s launched with the new double-cradle, oil-bearing frames and running gear, the frames came powder-coated in dove gray. It proved unpopular and late 1971 model year, they went back to black frames.

BELOW: This 1971 BSA A65 Lightning features the black frame. Note the Lightning was the twin-carb hotrod 650.

THE END IS NEAR

You have to hand it to them. They were trying. The 1971 makeover of the BSA and Triumph twins was a bold and ambitious move that, done right, could have made a real difference in the fortunes of the two marques. But alas, it was too expensive, was already obsolete when it came out, it was too slow, and what’s more, it put off their traditional BSA buyers. At a time when BSA and Triumph were suffering from vibration problems, oil leaks, crappy electrics and shoddy workmanship, was a new frame the right place to put their money? Everything combined, the entire move to Oil-in-Frame for both BSA and, to a lesser extent Triumph, was an anticlimax. It took so long to get them to market that very few bikes were sold the first year. The market’s reaction was mixed, but certainly not enthusiastic about the new look. The new BSA A65 never sold nearly as well as the bikes they replaced.

ABOVE: The 1971 BSA A65 Thunderbird was the single-carb roadster version.

BSA PASSES INTO HISTORY

BSA had been in serious financial trouble throughout the 1960’s, despite phenomenal sales in Triumphs. Backroom political dealings (former Ariel and Triumph owner Jack Sangster, now a BSA board member, was stripping the company of its assets and selling them off cheap to improve the short-term bottom line) had gutted this once-mighty industrial giant. What little they had left they squandered on dead-end projects like Umberslade Hall, the BSA 350 Fury, scooters and trikes and a badly-designed oil-bearing frame that no one asked for. All of this and lots of bad management to go with it, swamped the company by 1972. Few 1972 BSA A65 machines were built. Small Heath stopped producing BSA’s to concentrate on building Triumph Tridents. BSA Motorcycles was no more, the end of a long line of wonderful motorcycles and amazing history. As a side note, BSA is still in business today, making air rifles, scopes and optics.

BELOW: The 1971 BSA A65 Firebird Scrambler was the off-road/street scrambler version with single-carb and high side pipes.

BSA A65 YEAR-BY-YEAR

1962 BSA A65

First year for the new unit-construction twins. The A65 breaks with tradition with a (barely) oversquare bore & stroke of 75mm X 74mm.

1971 BSA A70 Lightning

BSA’s ultra-rare, one-year-only 750 version of the A65. They accomplished it with an 11mm increase in stroke.

Check out these BSA BOOKS

BSA Motorcycles: The Final Evolution

The BSA Gold Star: Motorcycle History

Illustrated Bsa Buyer’s Guide (Motorbooks International Illustrated Buyer’s Guide)

BSA Unit Singles: The Complete Story including the Triumph Derivatives

Bsa Motor Cycles: Since 1950 (British Motor cycles since 1950)

BSA 500 & 650 Twins: The Essential Buyer’s Guide

How to Restore Triumph Trident T150/T160 & BSA Rocket III: YOUR step-by-step colour illustrated guide to complete restoration (Enthusiast’s Restoration Manual)

For more like these, visit our BSA BOOK STORE

|

PLEASE BUY MY NEW E-BOOK HERE 12 Chapters & over 100 original photos. My best work yet. ONLY $4.99! Thank you, Andy Tallone, your humble author Click here to buy now: |